As a Scot leading drug policy reform in the US, Michael Collins jokes that when he first started pushing for decriminalisation he found himself thrown out of offices and unable to get Washington’s big beasts to return his calls.

Mr Collins, originally from Glasgow and a former director at the Drug Policy Alliance’s Office of National Affairs, has worked with Congress on a wide variety of drug policy issues, including criminal justice reform and reducing overdoses.

Now working as strategic policy director for Marilyn Mosby, the state’s attorney for Baltimore, he believes Scotland should tackle its drug deaths crisis by pushing towards decriminalisation and daring Westminster to try to block it.

The powers to decriminalise drug use or possession are currently reserved to Westminster but Mr Collins believes Scotland should follow the examples of US jurisdictions that faced down the White House to tackle their own crises.

He cites the examples of cannabis reforms in Colorado and Washington, and Oregon, which voted to decriminalise the possession of heroin and other hard drugs in favour of advocating addiction recovery centres, despite federal opposition.

“I think one of the things the Scottish Government has to do is recognise that it has a lot of ability to push the envelope right now,” Mr Collins said. “Even if you really do believe Scotland can’t decriminalise drug use, there’s a lot of things they can be doing, in terms of having conversations with prosecutors about drug possession.

“Law enforcement and prosecutors make decisions every day about what types of crimes are most important to communities. If you make drug possession the lowest priority, that would be a step towards decriminalisation. I don’t think anybody believes that Westminster would step in and say they need to make it priority number one.”

A ‘step change’

Scottish ministers have promised a “step change” in the approach to tackling drug deaths after statistics published last month showed there had been 1,264 drug-related deaths in Scotland in the past year, a 6% rise.

The death rate from overdoses is 15 times above the European average and is approximately three-and-a-half times higher than the UK as a whole.

The issue has become so large it now bleeds into other Scottish policy areas, such as policing, housing, justice and welfare, and ministers have promised a multi-spectrum approach to tackling the problem.

Last month’s harrowing figures led to the resignation of Joe FitzPatrick as public health minister and cleared the way for the appointment of Angela Constance as a new, dedicated drugs policy minister.

Ms Constance will take part in a virtual meeting with Mr Collins in the coming weeks to discuss how his experience can help.

His office in Baltimore has been attempting to replicate the success of countries like Portugal in reducing drug-related deaths and overdoses, despite strong opposition.

“We stopped prosecuting drug possession, sex work, and made efforts to reduce the prison population,” Mr Collins said. “It’s not like the Republicans and Donald Trump have thanked us for doing that, they are absolutely outraged and trying to fight us.

“But that is a fight we’re willing to have. We feel very confident about what we’re doing and if Donald Trump wants to stand up and say taking a public health approach to drug possession is an outrage then we’re happy to have that debate.

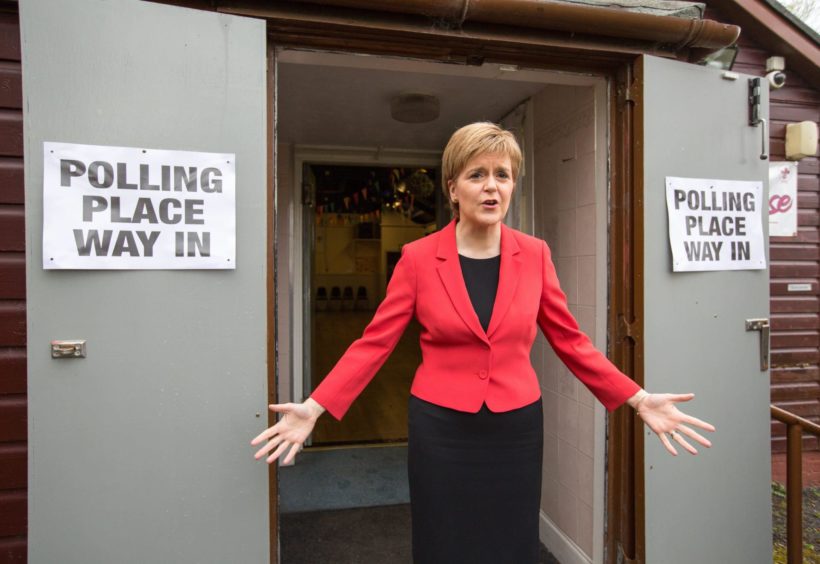

“By the same token, if Nicola Sturgeon is willing to say she’s going to pass laws in the interest of saving Scottish lives and Boris Johnson or the Home Office want to challenge that, she should say ‘we’ll have that debate or even fight it in court’.”

However, Professor Michael Keating, chair in Scottish politics at Aberdeen University, believes it is not realistic under the UK’s current political system for the Scottish Government to take such drastic action.

“Criminalisation is reserved, and as for prosecutions, that’s up to the Crown Office, really, and the Procurator Fiscal,” he said. “It’s not something that politicians can directly influence. They can’t order the Crown Office not to prosecute certain things.

“They can express views about priorities but the Crown Office and the police are independent.

“We could have a debate about that. There’s nothing to stop the Scottish Government saying it wants to have a debate about what it would do but that then becomes a very sensitive issue.”

Prof Keating said the “general consensus” in Scotland is to look at problematic drug use as a public health issue, whereas in Whitehall “they see it is a criminal problem” so even incremental policy changes can be challenging.

He believes that blockage is further compounded by a “climate where anyone broaching reform will be accused of being soft of drugs and irresponsible” and a political system that struggles to address such issues “without it becoming highly ideological”.

Too cautious

Meanwhile, critics have accused policymakers in Scotland and the Lord Advocate, James Wolffe QC, of being too cautious over the issuing ‘letters of comfort’ that would allow safe consumption rooms to be set up.

Peter Krykant, a former heroin user, set up a Just Giving page to create his own mobile facility from a customised van after being infuriated by the spat between the UK and Scottish Governments. He met Nicola Sturgeon earlier this month to discuss the issue.

Mr Collins said the 43-year-old essentially forced officials to choose between arresting an individual for “doing something that saves lives” or listening to what he has to say.

“That shows me you can have this strategy of: better to ask for forgiveness rather than permission,” Mr Collins said. “In America, states went ahead with legalising cannabis in spite of the federal government, not because of it.

“In Spain, the Catalan government went forward with drug consumption rooms and other innovative overdose prevention measures in spite of central government.

“I think Nicola Sturgeon and the Scottish Government have to take that approach as well. They should be moving forward with these initiatives rather than being worried about what may come down the road from Westminster or the Home Office.”

Mr Collins believes the drug deaths issue has become more important for politicians “because we let it get to this stage” and there will be pressure because it is an election year to take action beyond “pointing to the big bad wolf in Westminster who won’t let us do what we want”.

Crowded out

But Prof Keating warned there is a risk of important local issues, such as drug deaths, being “crowded out” by wrangles over big constitutional matters such as Scottish independence and the fallout from Brexit.

“In some ways it suits all the parties to make it about those kinds of issues rather than addressing the problems,” he said. “And then, more generally, people start wondering how responsive the Scottish Parliament, not just the Scottish Government, is at getting those questions on the political agenda.

“It does bring into question the way devolution has been designed and whether it provides opportunities for people to get these issues addressed.”

Austin Smith, policy and practice officer at the Scottish Drugs Forum, said it had been difficult to get attention for drug-related issues because the spotlight has been on coronavirus, Brexit and Scottish independence.

He said the latest figures had “pushed things up the agenda” but he would like to see “an earlier focus on what is a very vulnerable group of people”.

Prof Keating said one issue about addressing something like drug deaths at the polling booth is identifying who is to blame for the issue, and stressed it is unlikely there will be any serious discussions about devolving drug laws before May.

“There have been opportunities to devolve this before and it didn’t happen, and I don’t think it’s going to happen any time soon,” he said. “There needs to be the will there to do it.

“There seem to be arguments for at least having a rational debate about this and election campaigns are not actually the best time to have that calm debate because people get heated about all sorts of things.”