The “invisible mugger” that sprang from a Wuhan wet market, coronavirus has robbed the world not just of its health, but has and will cause economic pain for years to come.

The global stock markets have seen huge falls since the outbreak began on December 31, with the Dow Jones and the FTSE experiencing their biggest quarterly drops since 1987.

Demand for oil has all but dried up as lockdowns across the world have kept people inside.

And unable to work, millions of people across the globe have been furloughed or placed on welfare.

In response, national governments have mounted huge firefighting operations, with unprecedented levels of state spending required to keep economies afloat – and this is just the beginning, what about the future?

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) says that the global economy will shrink by 3% this year.

In the UK, the economy is forecast to shrink by 13%, our deepest recession in 300 years.

The need to do social distancing will basically cut off large parts of international trade.”

Economist James Meadway

Over the summer period alone, economic output could plunge by 35% and the unemployment rate could more than double.

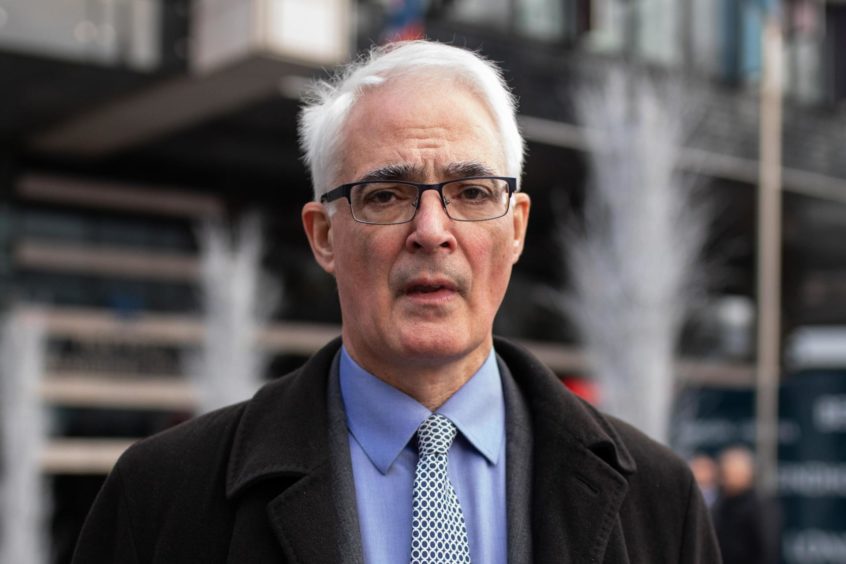

“My view is that the government will have to continue supporting the economy for a long time”, former Chancellor Alistair Darling said.

Mr Darling, who was in charge at the Treasury during the 2008 crash, told the Institute for Global Change think tank that there was “no alternative” to the current course of action.

“I did a similar thing 10 years ago, when things collapse all about you the government is the lender and insurer of last resort, our ability to recover will depend on having an infrastructure on which to build.”

Mr Darling said the recovery would be “gradual” and rejected talk of a “V-shaped” bounceback, or even a “U-shaped” recovery as in 2008.

Economic recovery

Economist James Meadway agreed. He told us that the scars of the pandemic would be visible on the global economy for years to come.

“With a crisis of this size and intensity, it’s very, very hard to believe it won’t have a severe long-term impact in a number of areas.”

Mr Meadway, a former chief economist at the New Economics Foundation, said the Treasury would essentially have to “wipe out the public sector” to repay the Covid-19 debt.

“That’s not going to sit well, as what we’re going through at the minute is a massive demonstration of the value of the public sector, so there’ll be public demand to try and maintain a high level of spending on it.

“You’ll see a realisation that the debt of the government is so large, that it’s implausible under any circumstances to try austerity to get rid of it.”

But former Greek finance minister Yanis Varoufakis told us austerity in some countries, such as Italy, “will be even worse” than 2008.

“The European Union is on track to lose hearts and minds across the continent and to reinforce the deflationary forces that deliver economic and psychological depression to a majority of Europeans in a majority of countries.”

However, on the UK he said: “In Britain I suspect that Boris Johnson has learned his lesson from the manner in which self-defeating austerity destroyed the careers of David Cameron and George Osborne.”

If not austerity, then how will the UK manage its books in the years ahead?

There are only three other ways of reducing debt, currency manipulation, taxation, or write-offs – all with their own issues.

After the Second World War for example, the US was able to cut its debt by forcing savers to hold government bonds and by making real interest rates negative – which acted much like a tax on wealth.

“I would issue bonds to the tune of at 3% of national income”, Mr Varoufakis said.

“I would, at the same time, ask the Bank of England to support these bonds in the bond markets and I would commit the funds raised by a National Recovery and Green Investment Bank to invest in good quality jobs in all the areas that need to contribute to Britain’s green transition.

“Such a large and permanent investment effort would help the UK attain a sustainable path out of the present conundrum.”

Long-term impacts

Resolving the issue of national debt aside, economists also foresee the march of globalisation being halted.

“A move away from globalisation has been in train since the 2008 crisis, world trade as a share of the economy is lower than it was in 2008, cross border financial flows are 65% of what they were in 2007”, Mr Meadway said.

“The need to do social distancing will basically cut off large parts of international trade, I think we’ll have companies realising their supply chains are very vulnerable to these sorts of shocks and we’ll see them wanting to pull production back in house.

“There will also probably be a reduction in international travel more generally and a continued rise in home working.”

As more people end up furloughed or on benefits in any subsequent depression, there is also likely to be much greater scrutiny of the welfare system.

Andrew Fisher, who authored Labour’s 2017 and 2019 manifestos, said the increase in unemployment could, perversely, improve the benefit system.

“I think for a lot of people it will make them think and reassess things”, he said.

“Covid-19 has already thrown into sharp focus the fact the NHS is under-resourced and under-prepared, so in the labour market you’ll get a lot people experiencing life on benefits who probably have never been on them.

“The more people see the flaws in Universal Credit for example, the more they will demand change.”

AUDIO: Listen to the ‘New Normal’ series writers discuss their findings in this special Stooshie podcast

The increased role of the state in every aspect of the economy could therefore be one of the most recognisable lasting impacts of Covid-19.

We have already seen unprecedented schemes to pay wages, loan cash and give grants in addition to directing production and restricting movement.

Just like after the 2008 banking crisis, which ushered in systemic change in the financial sector, so too could the pandemic in other areas of the economy.

“You could expect more regulation of the labour market and how people associate with each other, you could also see manufacturers look to new supply chains and a fall in travel.

“This change is here to stay”, Mr Meadway said.