Can the Scottish Parliament call an independence referendum without Westminster’s consent? It’s a question that will likely dominate the months following the Holyrood election.

On the face of it, the answer is simple: no.

If a request for a section 30 order — which transfers the relevant powers from the UK Parliament to Edinburgh to hold a poll — is refused a referendum cannot, at least under the current understanding of the law, take place.

Why? The 1998 Act of Parliament that established Holyrood stipulates that the “Union of the Kingdoms of Scotland and England” is a reserved matter and therefore only Westminster can decide upon the Union, unless consent is otherwise given.

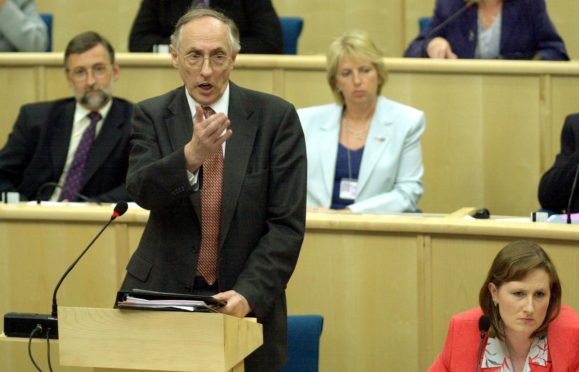

During the passage of the 1998 Act this very issue was debated by none other than the future first minister Alex Salmond and then-Scottish Secretary Donald Dewar.

Mr Salmond was keen to know whether a Scottish Parliament could legislate for a referendum, to which Mr Dewar responded: “It is clear that constitutional change — the political bones of the parliamentary system and any alteration to that system— is a reserved matter.

“That would obviously include any change or any preparations for change.

“I have made that clear in I do not know how many exchanges with Mr Salmond over the years.”

Ultra vires…

He adds: “A referendum that purported to pave the way for something that was ultra vires (beyond one’s legal power or authority) is itself ultra vires. That is a view that I take, and one to which I will hold.”

But significantly, Mr Dewar did not close the door completely. He added: “But, the sovereignty of the Scottish people, which is often prayed in aid, is still there in the sense that, if they vote for a point of view, for change, and mean that they want that change by their vote, any elected politician in this country must very carefully take that into account.”

Herein lies the rub. Mr Dewar was clear that an independence referendum called by Holyrood would not be legal under the terms of the Scotland Act, but he also believed that UK parliamentary sovereignty could, in political practice if not in law, be overtaken by a clear political statement of the “sovereignty of the Scottish people”.

Scotland has had an SNP government since 2007 and 2021 is likely to return another pro-independence majority. Is the continued refusal of a section 30 order really within the spirit of the 1998 Act?

Road to referendum

The SNP’s constitution secretary, Mike Russell, is clear; he has argued that there is no “moral or democratic justification for denying” a request and has warned the Scottish Government will put the 1998 Act to the test in the courts if required.

Mr Russell, in the SNP’s “road to a referendum” policy paper published in January, said if his party won another majority the choice for the UK Government would be to either agree that the Scottish Parliament already has the power to legislate for a referendum, agree the section 30 order, or take legal action to dispute the legal basis of the referendum.

“Such a legal challenge would be vigorously opposed by an SNP Scottish Government. The issue of whether there should be such a referendum is different from the issue of whether Scotland should be independent,” he said.

The UK Government has not said whether it would refer the Scottish Government’s intended Bill to the Supreme Court, but statements from Scottish ministers suggest they anticipate a challenge to be made.

SNP MP Joanna Cherry QC anticipated that any court would deploy “a process of statutory interpretation”, she also expected: “The UK Supreme Court and indeed Scotland’s Supreme Courts, to look to the wider constitutional context and to have some comments to make about a Government which does not allow a second indyref when there is a clear electoral mandate in favour of one.”

This was the approach of the Supreme Court of Canada when, in 1998, it was asked to rule on the possible secession of Quebec.

The Canadian government hoped the Court would confine itself to the wording of the Canadian Constitution, which does not contain a secession clause.

Instead, the Court concluded that: “The federalism principle, in conjunction with the democratic principle, dictates that the clear repudiation of the existing constitutional order and the clear expression of the desire to pursue secession by the population of a province would give rise to a reciprocal obligation on all parties to Confederation to negotiate constitutional changes to respond to that desire.”

The legalities therefore remain uncertain, but what we can be sure of is that 2021 will be a crucial year for the fate of the Union.