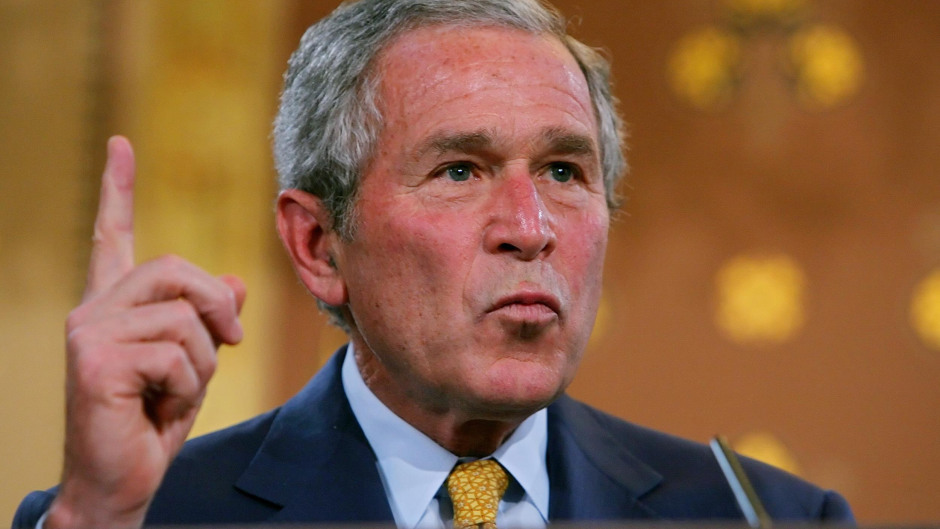

Britain’s invasion of Iraq was based on flawed intelligence and launched before peaceful options for disarmament had been exhausted, Sir John Chilcot said today.

He also condemned the decision-making process that led to the conclusion there was a legal basis for war as “far from satisfactory”.

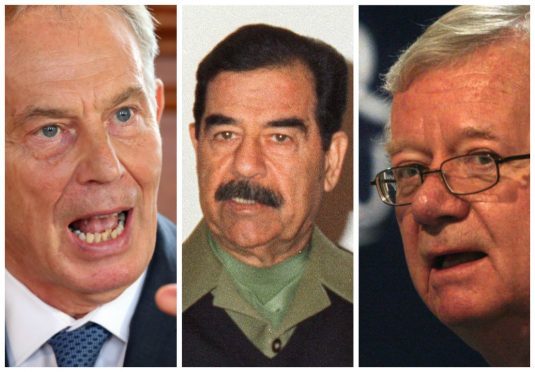

And – in a damning attack on Tony Blair – he stressed the UK’s relationship with the US does not require “unconditional support where our interests or judgements differ”.

Sir John made the remarks as he set out his long-awaited 12-volume report of the Iraq Inquiry, which considered UK policy from 2001 to 2009.

Almost seven years in the making, he presented his findings in front of some of the families of soldiers who lost their lives.

As well as casting doubt on the justifications behind the decision to join the US-led invasion, he bemoaned “equipment shortfalls”, describing the Ministry of Defence as “slow to respond” to the threat from improvised explosive devices (IEDs).

Sir John said: “We have concluded that the UK chose to join the invasion of Iraq before the peaceful options for disarmament had been exhausted.

“Military action at that time was not a last resort.”

Judgements about the severity of the threat posed by Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction (WMD) were presented with a “certainty that was not justified”, he added.

And despite “explicit warnings”, he said the consequences of the invasion were “under-estimated” and planning for Iraq after Saddam Hussein “wholly inadequate”.

He described his report as an account “of an intervention which went badly wrong, with consequences to this day”.

In March 2003, he said, there was “no imminent threat” from Hussein, the strategy of containment could have been “adapted and continued for some time” and the majority of the UN Security Council supported continuing inspections and monitoring.

Most members of the security council could not be convinced military action was justified or that peaceful options had been exhausted, he added.

He went on: “In the absence of a majority in support of military action, we consider that the UK was, in fact, undermining the security council’s authority.”

The inquiry, begun in 2009, never set out to determine whether or not military action was legal.

This question can only be resolved by a “properly constituted and internationally recognised court”.

But Sir John said: “We have however concluded that the circumstances in which it was decided that there was a legal basis for UK military action were far from satisfactory.”

On 24 September 2002, Mr Blair made a statement to the House of Commons on Iraq’s capabilities.

Sir John said his judgements were presented “with a certainty that was not justified”, adding the joint intelligence committee should have made clear to the prime minister that the assessed intelligence had not established ‘beyond doubt’ either that Iraq had continued to produce chemical and biological weapons or that efforts to develop nuclear weapons continued.

The committee had also judged that as long as sanctions remained effective, Iraq could not develop a nuclear weapon.

Sir John additionally highlighted Mr Blair’s comments to the Commons in March 2003 about the potential threat posed to national security by terrorist groups in possession of WMD.

The Whitehall mandarin said: “He had been warned however that military action would increase the threat from Al Qaida to the UK and to UK interests. He was also warned that an invasion might lead to Iraq’s weapons and capabilities being transferred into the hands of terrorists.

“It is now clear that policy on Iraq was made on the basis of flawed intelligence and assessments. They were not challenged, and they should have been.”

Pointing to “equipment shortfalls”, Sir John said there was little time to prepare three brigades after the UK’s military contribution was settled in mid-January 2003.

He added: “The risks were neither properly identified nor fully exposed to ministers.”

He also paid tribute to the “great courage” shown by British service personnel and civilians deployed to Iraq, more than 200 of whom died, alongside at least – and “probably many more” – mostly civilian Iraqis.

He criticised delays in providing medium-weight protected patrol vehicles, in light of the IED threat, which “should not have been tolerated”.

And he insisted the UK did not have the resources to be conducting two “enduring campaigns”, in Iraq and Afghanistan, as it was from 2006.

Sir John said Mr Blair did not establish clear ministerial oversight of UK planning and preparation, failures which continued to have an effect after the invasion.

He added that although the UK was part of the Coalition Provisional Authority and fully implicated in its decisions, it “struggled to have a decisive effect” on its policies.

He continued: “The Government’s preparations failed to take account of the magnitude of the task of stabilising, administering and reconstructing Iraq, and of the responsibilities which were likely to fall to the UK.

“The scale of the UK effort in post-conflict Iraq never matched the scale of the challenge. Whitehall departments and their ministers failed to put collective weight behind the task.

“The UK military role in Iraq ended a very long way from success.”

In a blistering attack on Mr Blair, Sir John said the then PM had “overestimated his ability to influence US decisions on Iraq”.

He went on: “The UK’s relationship with the US has proved strong enough over time to bear the weight of honest disagreement. It does not require unconditional support where our interests or judgements differ.

“Mr Blair told the inquiry that the difficulties encountered in Iraq after the invasion could not have been known in advance.

“We do not agree that hindsight is required. The risks of internal strife in Iraq, active Iranian pursuits of its interests, regional instability, and Al Qaida activity in Iraq, were each explicitly identified before the invasion.”

Outlining lessons to be learned, Sir John underlined the importance of collective ministerial discussion and stressed civilian and military arms of government must be equipped properly for tasks.

He concluded: “Above all, the lesson is that all aspects of any intervention need to be calculated, debated and challenged with the utmost rigour.

“And, when decisions have been made, they need to be implemented fully. Sadly, neither was the case in relation to the UK Government’s actions in Iraq.”