Children’s online safety is a baffling topic for many parents and it’s hard to know where to look for advice.

Faced with the dizzying array of social media apps and headlines about online predators, conventional parenting wisdom is to delay, restrict or ban. After all, the statistics are scary – around 60% of young people are seeing pornography or adult content online. It’s no surprise then that only around half of parents think the benefits of social media outweigh the risks.

The problem is, swimming against the tide will only take us so far. Highland Council is a leader in digital learning in Scotland. It has handed out Chromebooks to every pupil in P6, P7 and secondary school, and over 100 smaller primary schools now have one-to-one access. The Council is also preparing to launch Ineqe, the safer schools app developed by Zurich, which will help parents get to grips with new education technology.

Head teacher Robert Quigley is currently on secondment to the council to promote online safety, in a position that’s the first of its kind in Scotland. He’s a passionate advocate of digital learning and a father of four. Here, he offers some practical advice for kids’ online safety.

Children need to chat

What we as adults consider ‘sociable’ will likely look very different to our kids. “I might say ‘No more Xbox’ to my 13-year-old son, and he’ll immediately tell me that now he can’t chat to his friends,” Robert explains. “As adults we need to address how we perceive online communication – we have a tendency to try to replicate conversations online but kids don’t do that. Try to see it from your child’s perspective. If you stop that access, what opportunity do they have for socialisation?”

The temptation for parents is to take charge of that socialisation ourselves and allow kids to chat on specific, pre-agreed apps. This doesn’t really address the core issue. “If you’re a teenager and your friends are all drinking coffee in Starbucks, but your parents only let you hang out in Costa Coffee, the reality is you’re missing out socially.”

Walk alongside them

The reality is, blocking certain apps and games is a losing battle. Instead, Robert highlights the importance of having open, non-judgemental conversations. Leave your assumptions at the door, and ask your child what they want to access, and why they want to access it. Use their answers to start a discussion about the risks and bad behaviours they might find on there, and how to tackle those. You might think that parental controls and filters will block out any inappropriate content, but the reality is they’re never 100%. For instance, many porn sites now use innocuous sounding web addresses to get around filters.

“Children’s online safety isn’t just about blocking dangers but about how we help our children to cope with them,” says Robert. “You can say, ‘Okay, you want Snapchat, let’s do it together’ and then discuss how to handle any issues that might crop up. It’s about walking alongside them.”

Watch out for secret apps

The risks of not tackling online safety head-on is that kids find their own secret workarounds – and there are plenty of unscrupulous app developers ready to help. At the moment, there is a popular app designed to allow users to create hidden vaults for photos, videos and even other apps. It looks like a calculator – and even functions like one – but has a pin-protected area that works like a second hidden phone.

“Apps like this really define what we’re up against,” says Robert. “Companies have become savvy in helping kids bypass age limits and parental controls, and we need to think outside of the box to tackle that.”

Ultimately, prevention is better than cure – so teach your kids to be responsible with technology from an early age.

Think resilience, not age

Age is one of the hottest topics when it comes to children’s online safety. Most social media apps have a 13 age recommendation, but these restrictions aren’t legally enforceable in the UK. Is there a ‘right’ age for Snapchat? When should you give in to demands for a smart phone?

Robert suggests a more personalised approach. “The way to gauge if they’re ready always comes down to their personal resilience. When my nine-year-old daughter wanted Snapchat we talked about how she wanted to upload amazing videos of her gymnastics, but I asked her how she would feel if people made nasty comments about it. Ask yourself: could your child cope with the bad stuff, or would they crumble?”

Reconsider the S1 mobile phone

Similarly, the timing for a first mobile phone really depends on how they will use it. Many parents hand over a smart phone on the first day of high school, but is that a misguided rite of passage? Robert thinks so. “Why give a child a mobile phone at the end of the summer holidays? If they weren’t ready three months ago what makes them suddenly ready on the first day of term?”

Instead, Robert suggests introducing the phone in P6, and helping the child to get used to it in a supervised environment. Similarly, consider whether younger children need a mobile phone at all, when the apps they use will be widely available on tablets and games consoles.

Learn what they’re doing

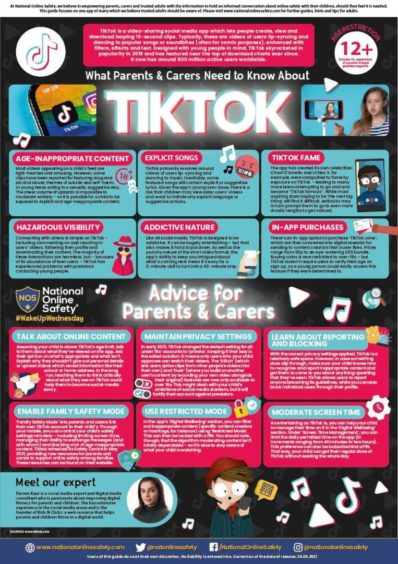

Knowledge is power. However you don’t need to know every app on the market to keep on top of children’s online safety. The good news is children and teens want to hang out where their friends are, so the most popular apps are a good place to start. Consider setting up the account with them and having an account of your own to keep an eye on their activity – they can earn more freedom and trust over time. As for specific children’s online safety advice, the National Online Safety website offers hundreds of excellent at-a-glance guides free of charge.

“You just need to be familiar with the content they’re consuming,” says Robert. “If it was a film, you’d watch it with them, watch it yourself in advance or read the reviews. If they do see inappropriate content, empower them to talk about it. Remember, they might hear it in the playground anyway.”

Ease out of screen time

Social media and gaming can feed a need for instant gratification, so it’s important to be set sensible limits. “Online predators look for the 1% of people who are vulnerable,” says Robert. “We tend to think of vulnerable children as those with additional support needs, low self esteem, mental health issues…. actually a vulnerable person could just be someone who’s having a bad day. They come home from school and see the dangling carrot of an instant positive kick.”

That kick is highly addictive, and kids need time to ‘reset’ emotionally when they come offline. “When you come out of the cinema you don’t just go from this dark, immersive experience straight out into the light,” says Robert. “You get eased into a dimly lit corridor first. Don’t just yank them back into the real world, give them time to calm down, and positive options for activities they can do next.”

Model positive behaviour

As with any parenting issue, the most powerful thing is to lead by example. Keep your social media clean, respectful and well considered, so you’re modelling appropriate online behaviour for your child. Robert calls it the ‘Granny rule’ – if you wouldn’t be comfortable showing it to your grandmother, don’t put it up online.

Remember, as a parent, you’re already armed with the tools you need to keep your child safe online. You know your child. What they can handle. Where they might stumble. And how you can help. The key message from Robert: “Ultimately, digital parenting is still just parenting.”

More from the Schools and Family team

Moray mum saves baby’s life during choking spell

The man with the plan to teach us Gaelic in weeks

Back to school hacks – top tips to tackle early morning mayhem