Highland parents say they feel abandoned by the services which are meant to support children with autism.

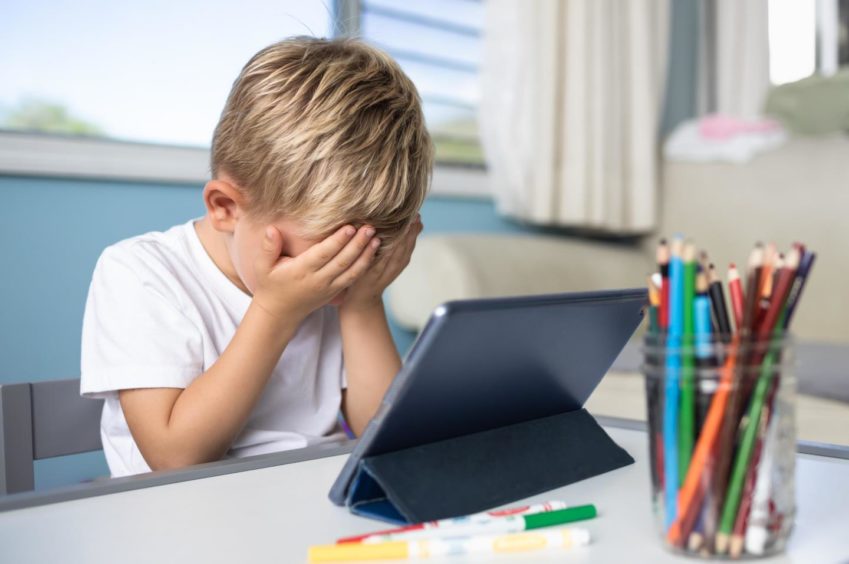

Caring for children with autism is a demanding job at the best of times, but lockdown has piled on the pressure.

Parents and carers say support services are patchy across Highland, but the pandemic has pushed the system to breaking point.

The three families we spoke to all have unique circumstances, yet share some things in common.

All have partially or fully withdrawn their autistic children from mainstream education. They say they feel overwhelmed and alone. And all are fighting for a better future for their kids.

Jayne Scollay, from Wick in Caithness, articulates it well: “I’m not vulnerable. I’m not desperate or shouting out for help. I just want people to recognise the things autistic children could have that would make their lives better and support their families.”

Difficult days

Mrs Scollay has first hand experience both as a parent to two autistic sons and as a former social worker. She gave up work six years ago to become a full-time carer to Ivan, now nine. Ivan is autistic and non-verbal, and also suffers from associated conditions including cyclical vomiting syndrome, a rare disorder that causes repeated episodes of being sick lasting hours or even days.

His conditions mean that life in the Scollay household can be relentless. “Sometimes life feels like just days,” says Mrs Scollay. “The last couple of years there’s been no break. The only time I’ve had to myself was when I was in hospital.”

Caring for two vulnerable kids has put a strain on Mrs Scollay’s own physical and mental health. She recalls one incident when Ivan attempted to run off the pier in Wick and she broke her coccyx in the process of saving him.

Round-the-clock care

Ivan has no sense of fear or danger – his diagnosis aged two followed him breaking both arms and showing no reaction. “He’s a sensory thrill seeker,” explains Mrs Scollay. “If you’re in a house with stairs he’ll jump straight from the top without a thought.”

This lack of risk perception coupled with a childish sense of adventure gave rise to two frightening experiences for the Scollays. In May 2020, the height of lockdown, Ivan disappeared from home, sparking an extensive search. “I was out in the street, screaming,” recalls Mrs Scollay. “Everyone was out looking for him, even neighbours we’ve never spoken to.”

The police found Ivan playing on a busy road near the river, unharmed and delighted with his adventure.

Following the incident, the family added alarms and extra security measures to the house, but within a fortnight Ivan had jumped the garden fence and walked out into traffic. “There’s no security measures you can put in place that cover every scenario, especially as they get older and bigger,” says Mrs Scollay. “Twenty seconds is all it takes.”

According to a study in the American Academy of Pediatrics (sic), a shocking 49% of children with autism disappear from a ‘safe’ environment, which adds to the challenge of accessing support services and respite care.

Feeling left out

Under those circumstances, you might think that school would offer support and respite for parents of children with autism. Sadly, in some cases it’s just another challenge to tackle.

Ivan attended autism unit ‘SCoPE’ at Noss Primary School, Wick, part-time before lockdown. But the school community was not an inclusive place for Ivan, says Mrs Scollay.

“The school wanted parents to complete permission slips just to play with my son,” says Mrs Scollay. “He’s not violent, it felt like discrimination. I’m not blaming individuals but attitudes need to change and the support is just missing.”

Mainstream isn’t for all

Mrs Scollay had a similar experience with her eldest son, Innes, 14, who is about to enter S3 at Wick High School. The new £50m campus has faced criticism in the past for being unsuitable for children with autism. “His autism takes the form of extreme social anxiety,” says Mrs Scollay.”Add in teenage hormones, and life is really challenging for him. He’s currently only managing 20 minutes a day at school.

“We spent months just trying to coax him out of the car. The new school building opens straight into the busy canteen. That’s a huge barrier for autistic kids. Ivan will face those same barriers in years to come.”

Some 20 miles down the Caithness coast in Lybster, another family explains why a mainstream approach can leave children with autism excluded. Nine-year-old Alice has high functioning autism and found the first national lockdown deeply traumatic. Teachers tried their best, but struggled to provide resources that were suitable for pupils with additional support needs.

“When lockdown hit the world just closed off for Alice, and she struggled to understand where her routine went,” says Mum, Jess. “She regressed to behaviour I’ve not seen since she was three, lashing out and being harmful to herself. For autistic kids, school is school and home is home, and she’s rigid with that.

“The work coming through from school just wasn’t suitable for Alice, and working online caused sensory overload. I’m not bashing the school. They did the absolute best with what they had, but they were caught on the hop and it’s hard for mainstream education to meet the needs of every child.”

Lockdown highs and lows

To add to the strain, Jess’ husband Peter was struck down with long COVID and spent several weeks unable to get out of bed. “He’s a fit and healthy man with an active job, and suddenly he couldn’t even stand up for a shower,” says Jess. “Peter has recovered now but it was a scary time.”

Alice is now back at school, with one half day of home schooling. “The school supported us with a flexible education agreement so we could give Alice some one-to-one time learning key life skills,” says Jess. ” We wouldn’t have thought to do that without lockdown, so there was some positive that came from it. Overall though, it was a really difficult time.”

The last straw

Sadly, for one family in Inverness, lockdown had a devastating impact. Sylvia Mackenzie is full-time carer to a severely autistic adult son and has kinship care of her nine-year-old autistic grandson. On the day Sylvia spoke to the Press & Journal, she had just said her goodbyes to her grandson James (his name has been changed to respect child’s privacy). After many months of agonising and preparing, Sylvia has enrolled James at a boarding school for children with additional needs.

“I’ve fought and advocated so much, I’m exhausted today,” she says. “I can’t even think about what’s happened. However, the relief of knowing he won’t have to attend mainstream school anymore outweighs my sadness. I had to do this for him. I had to give him an education.”

“He kept asking for help”

Sylvia is a long-time campaigner for children with autism, and passionately believes that mainstream is not for every child. She wants to see a special school open in Highland, after what she views as a “complete failure” of James’ school to meet his educational and personal needs.

“My grandson was bullied in mainstream school. The classroom was too big and he couldn’t get the support he needed. These kids get lost in the system and they feel depressed. He kept asking people for help. I think he will get it at this new school.”

Lockdown learning materials catered for the mainstream class but not for James, according to Sylvia. “I didn’t know where he was in his learning. Some kids thrived in lockdown because their parents could give one-to-one support, but I have other kids at home so James was losing out. The support for parents and carers isn’t there. If you don’t ask you don’t get, and if you don’t know, you can’t ask.”

Highland Council maintains that support for families of children with autism was maintained throughout the pandemic. A spokesperson said: “Support is available across Highland. This is offered through the Highland Practice Model process, which proportionately identifies and supports need as it arises. Therefore there is no waiting list for support.

“During the pandemic, council staff were able to continue to provide support to families with children with autism and additional check-in sessions were put in place with families either directly or remotely.”

Parent campaigners

This is not the experience shared by these parents, who have become outspoken advocates for children with autism. Jess Sutherland is a member of the Caithness Autism Support Group on Facebook. “We’re a really close knit group and it’s good to know you’re not on your own,” she says. “Jayne Scollay is fantastic.”

For her part, Mrs Scollay sees advocacy as a responsibility – though it can feel like another load on an already-heavy burden. “I couldn’t do a lot of this without the knowledge and experience I gained from my health and social care degree and professional practice,” she says. “I try to pass that on and share it, and I join committees and help where I can. Parents have to do the fighting. That’s frustrating and it takes a toll on my own health.”

Losing battle

It’s a familiar picture according to the National Autistic Society Scotland. “We frequently hear from families across Scotland waiting months and even years for a diagnosis of autism and the services that should follow,” says Scotland Director Nick Ward.

“We hear families endlessly fighting the system to get much needed support within school and the community, a fight that they often lose, leaving them in crisis.

Support for children with autism has been deeply impacted by the pandemic, says Mr Ward. “Covid has drawn much of this into sharp focus as many families have seen critical support withdrawn and waiting lists lengthen as health and care services have been focused on responding to the pandemic.”

For the Scollay family, lockdown was a watershed moment. “The pandemic actually helped as we realised Ivan was developing better at home with me,” says Mrs Scollay. “He’s as bright as a button but mainstream education failed to see that. The wrong environment can be traumatising for children with autism. He’s so much happier at home and I’m relieved not to be battling education all the time.”

One change is particularly striking: Ivan is starting to speak.

The Scollays, like all parents, simply want their children to thrive. So while the days can be punishing, the rewards are priceless. “All the stress is wiped out when I hear his voice,” says Mrs Scollay. “That’s our everything.”

More from the Schools & Family team

Online safety – Why you should scrap the back-to-school mobile phone, and other tips

Learn Gaelic in three WEEKS? Meet the man who claims he has the key to revitalising the language

Could 2-minute brain breaks and LESS planning help Scottish schools catch up with Finland?