In the early days of the Second World War, Britain was in danger of being overwhelmed by the might of Nazi Germany.

As tens of thousands of soldiers, sailors and pilots were recruited to combat the military menace, there was an army of others working relentlessly to unlock the secrets which might provide crucial information.

Today marks the 80th anniversary of the first time a German Enigma message was successfully read by the British, through the efforts of scientific genius Alan Turing.

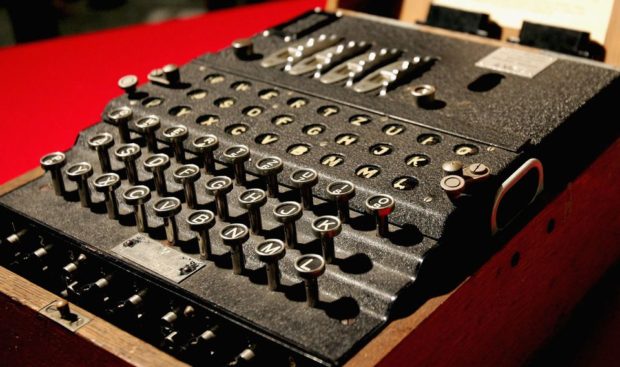

The Germans had been using Enigma machines since 1924, and had gone to remarkable lengths to orchestrate ever more elaborate codes.

But Turing unlocked the key, while working alongside his colleagues behind closed doors at Bletchley Park, the estate in Milton Keynes which became the principal centre of Allied code-breaking during the conflict.

Turing’s work was subject to the Official Secrets Act and he was vilified because of his homosexuality, as documented in 2014 film The Imitation Game.

But he has been posthumously celebrated, and his face appears on the Bank of England’s new £50 note.

He will be at the centre of an interactive event, organised by Bletchley Park authorities today, to mark his momentous contribution to the Allied effort.

David Kenyon, research historian at Bletchley Park, said: “We are looking forward to using the 80th anniversary of the first British wartime break of a German Enigma message to help bust some myths and highlight the incredible international teamwork that made it happen.

“We will be sharing little-known facts and stories, and opening up for a special live Enigma Q&A answering lots of questions about this event, the further breaks that followed and what it all meant for the rest of the war.”

Mr Turing visited Paris and with French and Polish cryptographers on January 17 in 1940. He then returned to the UK and, on the following Monday, was instrumental in cracking the German Enigma code.

The decrypting and decoding of German army and air force, and later naval, Enigma messages continued with increasing success for the rest of the war. It reached a peak in 1944 when more than 3,000 messages were being broken and read every day.

Some military historians believe that the quality and amount of intelligence produced at Bletchley shortened the hostilities by two to four years.

Codebreaking operations at the site came to an end in 1946, but all information about the wartime operations was classified until the 1970s.

Aberdeen’s involvement at Bletchley Park

People from all different countries and backgrounds were involved in the vital work at Bletchley Park during the Second World War.

In 1942, Helene Taylor was recruited at the age of 21 from Aberdeen University and spent the rest of the conflict involved in code-breaking.

After leaving Scotland for only the third time in her life, she travelled to a place she did not know, lived with complete strangers, and carried out work which she could speak about to nobody outwith the Bletchley circle.

Miss Taylor, who later became Mrs Aldwinckle, had been chosen by a senior codebreaker, Stuart Milner-Barry, to work in Hut 6 – the department tasked with deciphering Enigma messages sent by the German army and air force.

She was asked to run a school to train United States personnel on the procedures and secrets of codebreaking at Bletchley Park.

In doing so, she played an important part in cementing the British-American intelligence-sharing agreement which endures to this day.

In 1944, she worked in a section of Hut 6 called the Quiet Room, where she identified Enigma radio networks and analysed radio signals’ preambles and sign-offs.

She and her colleagues also played a crucial role in the lead-up to the Normandy invasion.

In a moving ceremony last July, Mrs Aldwinckle, at the age of 98, was presented with the insignia of Knight of the Legion d’honneur, France’s highest civilian and military honour, at the French Embassy.

An account of her wartime experiences can be found here.