As the generations of WWI veterans and their children die out, the opportunities to capture first-person accounts are fading. But a recent built-heritage survey of The Great War has revitalised many people’s quests to understand what happened on the Scottish home front 100 years ago.

Commissioned by Historic Scotland and the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland (RCAHMS), a special audit has revealed previously unknown aspects of Scotland’s wartime heritage.

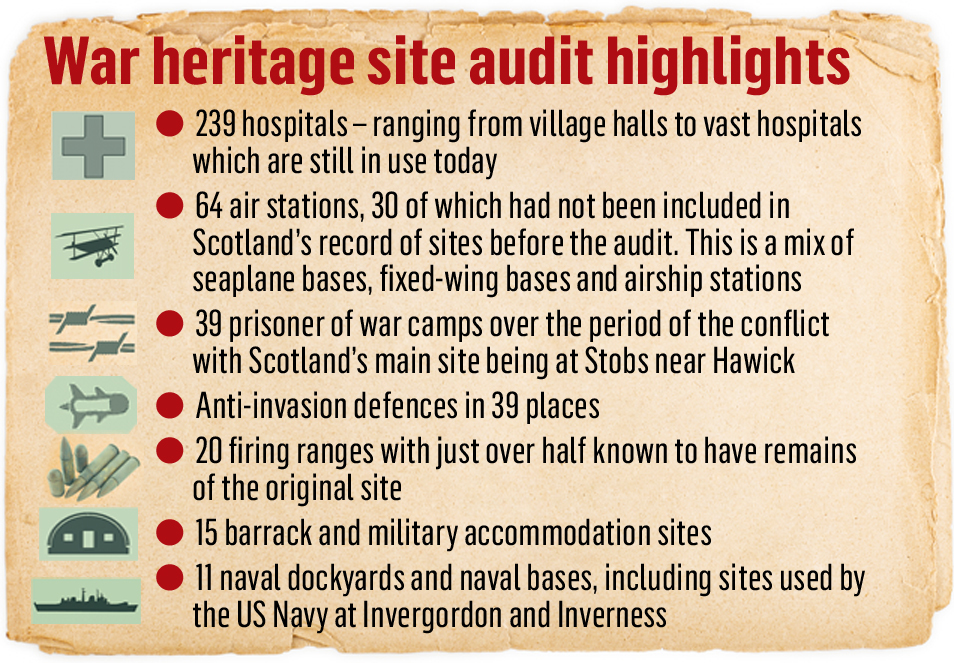

Carried out last year and published in February, the survey has revealed an astounding array of built-heritage sites and anti-invasion defences across the country, from military hospitals to air stations, firing ranges to naval bases, and prisoner of war camps to military barracks.

“We’ve been thrilled by the results,” said Allan Kilpatrick, archaeologist at the RCAHMS, who collaborated on the extensive audit.

The research process was primarily desktop-based, including scouring records contained in national archive databases and RCAHMS’s existing records. The number of WWI sites revealed in the process, Allan explained, far exceeded anyone’s expectations.

“We reckoned we had probably about 300 sites when we started, but we ended up with over 900, which is really significant. And we’re still finding more every week.”

The results, which are published in a report available on www.historic-scotland.gov.uk, have allowed the team of archaeologists and historians in both organisations to re-examine the current understanding of many activities which took place on home soil.

“For example, there was much talk about defences being built from the start of the war,” Allan continued, “but actually some are dated from the early 1900s, 10 years before the start. So it’s provided a fascinating insight into Scotland during WWI.”

While a large number of the sites

are based around the central belt,

there are many in the north, Highlands and islands. In Aberdeen, shining examples are the Torry Battery – a Victorian-era fort – and temporary hospitals in Esslemont Avenue and Schoolhill. Further north, near Clola, stands the former site of the Lenabo air station – a busy station where 1,500 personnel worked.

Moving round the coast, drill halls and firing ranges were a common finding.

“Coastal communities were often artillery bases because they could practise firing their guns out to sea,” Allan said.

“Inland, such as in Huntly and Oldmeldrum, they had rifle ranges either outside or inside. But most of the communities, especially on the seabord, had drill halls.”

The Cromarty Firth was a hive of naval activity, including the naval base at Invergordon which contained enormous camps with huts capable of housing 80 civilian dockyard workers each, compared to the comparative luxury of the 100 or so houses built for the Royal Navy, and the seven villas for dockyard officials.

Guarding the Cromarty Firth were massive gun placements – built in 1913 under the watchful eye of then First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill – and also the first anti-submarine boom defence nets to be built in Britain.

It was a similar story in Orkney and Scapa Flow, with the British Grand Fleet being stationed there from 1914. As a result, many sites of interest remain, including submarine mining fields, lookout stations, camps and batteries featuring heavily in the audit report.

It doesn’t stop there. A seaplane base in Shetland, a prisoner of war camp at Fort George, a Territorial Army Drill Hall in Stornoway, a gun emplacement on St Kilda, remnants of Scotland’s WWI built heritage can be found all over the north.

More are being found all the time, thanks in part to initiatives such as the Home Front Legacy project which builds on the Historic Scotland and RCAHMS audit. Community groups are being supported in their research into places associated with the Great War with an online toolkit (available at www.homefrontlegacy.org.uk) and guidance for recording the remains of surviving sites, structures and buildings around Britain.

“The great thing about the community approach is they have a better handle on local history. Local communities can come together and we can work with these groups to help explain what’s there,” said Allan.

Key to the success of all attempts to learn more about our combined built heritage, he explained, is our rejuvenated enthusiasm to learn about our own ancestors.

“There’s a real move to investigate what our great and great-great grandparents did during the war,” he said.

“Everyone has a connection to WWI in some way or another. It could be there was a soldier in the family, or a great-grandmother who worked in some factory making kilts or gas masks. So there are all these personal stories out there, and the more we can bring together, the better resource we will have.

“I’ve always said about WWII that this is our final chance to get the memories of the veterans, and it’s the same with WWI. In the next five years, there will only be a handful of the children and grandchildren of WWI veterans who have memories to share.”