In recent years, Scotland has been handed the inglorious title of drugs death capital of Europe.

It’s a grim accolade but in reality, the country has been ravaged by addiction for decades and those in power have done very little about it.

Could that horrific title alone be the catalyst for change though?

It wasn’t long ago Glasgow was Europe’s murder capital.

In that case, a pioneering project saw knife crime slashed to a fraction it once was and Scotland rid itself of such horrible branding.

As we often see when a place is held up as an example of ‘the worst’ in anything, change can happen quickly.

An old proverb says necessity is the mother of invention; let’s hope shame is just as powerful.

It’s what prompted authorities to launch the Dundee Drugs Commission and, subsequently, Scotland’s Drug Deaths Taskforce.

Both were tasked with getting to the root of the problem and making real practical recommendations for change.

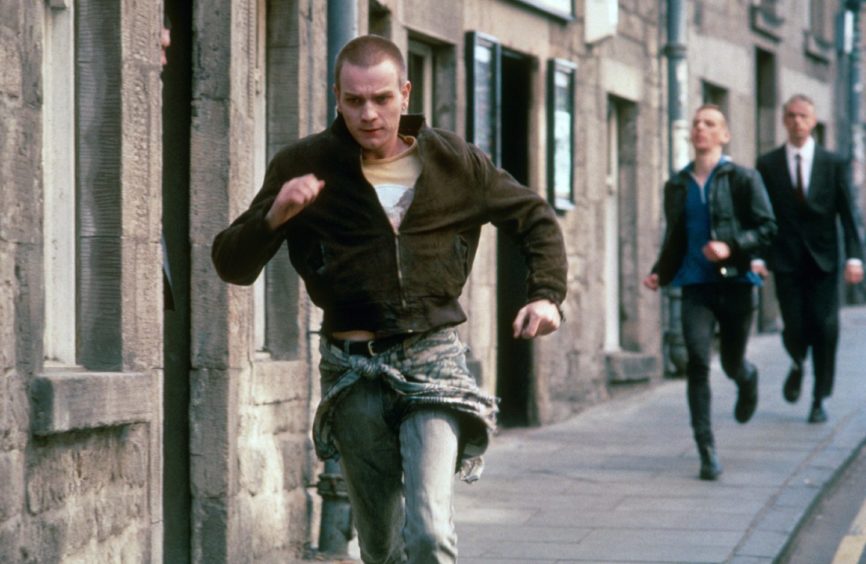

Trainspotting generation only one factor

I must have sat through at least 30 hours of evidence and discussion in sessions of the Dundee Drugs Commission.

It doesn’t mean I have all the answers but a browse through old notebooks might help with some context as the latest deaths figures are released.

What’s the issue in Scotland? Why are so many people addicted to hard drugs and why are so many dying from overdoses?

My answer to that would actually be quite a simple one.

It’s because not much has actually changed in the last 30-odd years.

Many in the ‘Trainspotting generation’ hooked on heroin in the 1980s have been dying in recent years but actually, there are newer drugs doing exactly what ‘smack’ did back then.

A type of ‘fake Valium’ called etizolam, for example, is implicated in around half of deaths in Scotland because its strength is unpredictable.

And they are cheap too at about a £1 a pill.

Drugs deaths have been declared a public health emergency in Scotland just recently — 30 years late on that one perhaps.

Many are beating the drum for decriminalisation, and more power to change laws was a strong recommendation from the Dundee Drugs Commission.

One of the main issues that appears to stunt Scotland’s drive to turn the tide is that the government here does not actually have the power to take the most radical steps.

For a country that has a higher rate of deaths due to overdose than any other European country or the United States, that seems debilitating.

Dundee Drugs Commission

So, what was that first meeting of the Dundee Drugs Commission like?

It met in private and journalists were then invited in to the room to find out how it went.

It was tense. You sensed the eyes of the world were on Dundee and Scotland. Answers were needed — and fast.

Each monthly meeting over the next year or so delved in to a different area: mental health, primary care, methadone use, treatment delays, and so on.

The issue needed to be split between preventing deaths among those already addicted (and helping them back into society) and reducing addiction in the first place.

The fact that Scotland does not have the power to introduce safer injection facilities was one of the first topics discussed and one that the commission would have no direct power to change.

Not an ideal start.

The meetings over the next 12 months saw various experts come in to give evidence.

Dr Emma Fletcher, a consultant in public health medicine at NHS Tayside, said a lack of opportunity was the main driver in addiction and that this was mirrored in other deprived places in Scotland.

Others, such as Ann Eriksen, executive lead for sexual health and blood borne virus at NHS Tayside, said a stronger relationship was needed between addicts and health services as many people had been “bruised” from previous experiences.

GPs from specialist practices in Edinburgh chipped in to argue opioid treatment should be supplemented with treatment to address deeper personal issues.

Radical measures were thrown into the mix too with one member suggesting children as young as 12 could be trained to use anti-overdose drug naloxone to save the lives of parents.

After sitting through many, many, hours of this, I was left with the feeling that the entire approach to addiction in this country is misaligned and has been for a long time.

Scotland’s problem

It’s also clear that most of the issues discussed were Scotland-wide and not specific to Dundee.

Poverty and lack of opportunity tend to go hand-in-hand with higher rates of addiction and so, to simplify things, that’s why a long-neglected Dundee is so badly affected.

But there are plenty of other areas in Scotland within towns and cities with comparable rates.

The pristine tourist’s idea of Edinburgh, for example, wouldn’t include the serious social problems in parts of Leith or Pilton.

It’s the same in Glasgow and even oil-rich Aberdeen has pockets of extreme poverty.

That’s not to mention the many towns blighted by those exact same issues.

It’s not uncommon for some Scots to be able to reel off a list of people they’ve known who have succumbed to drug abuse.

Scotland has had a terribly slow reaction to the crisis and, like many countries, has a completely ineffective stance on drugs.

What purpose does it serve to criminalise someone for possession of a small amount?

Running in wrong direction

Who knows what could have been achieved by a quick and radical response in the 1980s?

Decades of running in the wrong direction will take a long time to come back from but it simply can’t take another 30 years.

Future generations will have a name for this period and it won’t be nice.