From 2018 there has been a huge increase in Vietnamese victims being discovered in Scotland with trafficked humans found across Aberdeen, Tayside, Fife and Inverness last year.

The sharp rise in numbers could be a sign of established OCG networks already operating in England expanding their businesses north of the border.

Mimi Vu, an anti-human trafficking expert with Raise Partners, believes the victims located in Scotland are being exploited by satellite branches of the criminal gangs operating in London.

“The OCGs running the nail bars and car washes as fronts for illegal activities, and also cannabis growing, have been operating in the UK for a long time,” she said.

Worryingly, as the Vietnamese cartels move into new territory in Scotland they are also exploring new illegal markets on the continent.

Due to over-saturation in the cannabis farm industry, Vietnamese OCGs are instead turning their attention to crystal meth.

The highly addictive drug is easily cooked up in warehouses and homes with the ingredients able to be bought in most supermarkets.

Mimi believes that the London-based OCGs are also preparing to begin crystal meth production.

“The idea has already been planted (in the UK) – it just takes time for authorities to become aware of it,” she said.

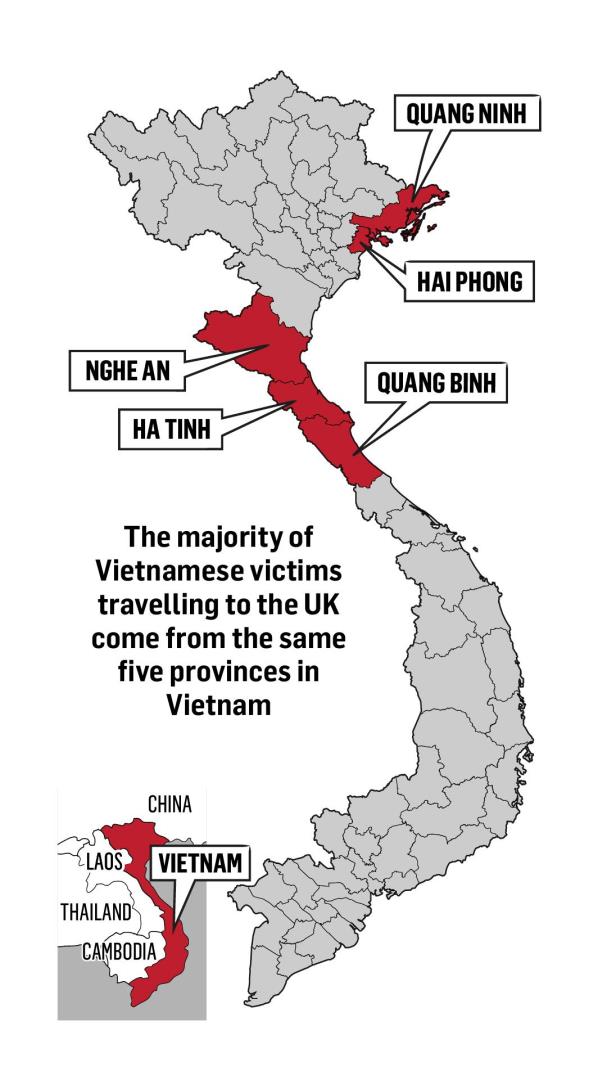

The five provinces

The UK has long been a sought-after destination for Vietnamese migrants hoping to earn their fortune to take back home.

Traffickers prey on this.

They charge victims huge sums of money, $20,000 to $30,000, to smuggle them out of Vietnam and into Europe.

The people from these five provinces have historical links of travelling to the UK and Europe for employment.

Many Vietnamese migrants travelled to Europe in search of work after the end of the Vietnam War in 1975 as part of a labour export programme.

“They had sent these people to Europe, to former Soviet bloc countries, Eastern and central Europe, to work legally as overseas labour,” explains Mimi.

The OCGs exploit these historical links of the Vietnamese diaspora to run their human trafficking networks.

“It’s no coincidence that the cities where you have large Vietnamese diaspora groups are also the headquarters for the various Vietnamese-ethnicity led OCGs that all play a part in this smuggling and trafficking route.”

Smuggling routes – From Hanoi to Scotland

The traditional smuggling route utilised by traffickers can be a long and frightening journey for the victims.

From Hanoi in Vietnam they travel by plane to Russia, usually Moscow, and then over land through Latvia, Lithuania, Prague, Warsaw in Poland and on to Berlin.

From there they can make their way through Amsterdam, Belgium and France.

The high level of organisation between the different criminal groups is the key to their success.

“First you have to understand that this is run by organised crime, and when I say organised crime I mean mafia,” says Mimi.

“It is transnational organised crime which means you have several different groups of organised crime working together, cooperating together.”

“They work together and then also with non-Vietnamese OCGs.

“There’s ad-hoc people like the drivers, the guy who organises the drivers, the money launderers and the guys who run the underground rat houses – so it’s a whole network.”

Dangerous journeys fuelled by exploitation

What begins as the victim agreeing to be smuggled out of Vietnam quickly descends into something else entirely.

The high-risk journeys, which can take anything from three to four weeks to three to four years, are fuelled by exploitation.

Migrants can fly to Russia and enter legally where they are met by affiliates of the OCG.

They are packed into cars and vans and smuggled by land across the Russian border illegally where the OCG now has complete control over them.

Women along with boys and girls under the age of 18 are at very high risk for sexual exploitation en route.

Everyone is at risk for forced labour, being made to work in sweatshops.

The longer the journey, the higher the level of exploitation.

The long and dangerous journey to the UK was brought to a harsh and tragic light on October 23, 2019, when the bodies of 39 Vietnamese migrants were found dead in a lorry trailer in Essex.

The youngest of the victims were two 15-year-old boys. Ten teenagers died in total.

The eldest victim was 44-year-old Le Trong Thanh.

All 39 had died from asphyxia and hyperthermia. A judge would later call their deaths “excruciatingly painful”.

The victims, 31 males and eight females, had suffocated, trapped in the container as it travelled from the Belgian port of Zeebrugge to Purfleet in England on the evening of October 22.

The temperature in the trailer was reported to have risen steadily while the ship was at sea, hitting 40C, as the carbon dioxide levels also increased.

They tried desperately to escape their fate, using a metal pole to try and punch through the roof – a dent in the interior proof of their struggle.

Some managed to make contact with families by phone as air in the container ran out.

At 1.38am on October 23, Essex Police were called to Waterglade Industrial Park to reports of 39 bodies.

The gang

The man that made the phone call to police was Maurice Robinson, 26.

He was a driver for a smuggling gang that had been organising transport into the UK by sea from Europe.

Robinson had collected the trailer from Purfleet.

It took him 23 minutes from discovering the bodies to ring 999. During that time he made contact with his gang instead.

On January 22 2021 he was jailed for 13 years and four months for his role in the operation.

The man who had towed the trailer into the Belgian port of Zeebrugge, 24-year-old Eamonn Harrison, was sentenced to 18 years.

Two of the ringleaders of the people smuggling conspiracy Ronan Hughes, 41, and Gheorghe Nica, 42, were jailed for 20 and 27 years respectively.

Three other men – Christopher Kennedy, 24, Valentin Calota, 38, and Alexandru-Ovidiu Hanga, 28, also received jail time.

Despite the long convictions of those involved, none are believed to be the true ringleader at the top of the OCG-chain in England.

That role is thought to be held by the shadowy figure of a Vietnamese-ethnicity man called Fong who runs a London-based OCG.

During the course of this investigation, many have said they believe that the true leaders of the Essex tragedy have never been caught.

Hostile environment

There is a belief within organisations close to the issue that stringent border controls are playing into the hands of traffickers.

Victims are forced to take on these dangerous journeys due to the difficulty in Vietnamese nationals gaining visas for western countries.

Caitlin Wyndham, of the Hanoi-based Blue Dragon Children’s Foundation charity, believes that a better system for legal and safe migration needs to be created.

“It used to be relatively safe to go to Europe and work legally for a while,” she said.

“It is now extremely dangerous.

“There is a desire from this end but clearly a demand from the UK and Europe for labour that is being met by people who are migrating there but can’t access legal means.

“Without legal mechanisms for people to be able to access work, especially low-skilled work, people smuggling will continue.”

One of the problems in tackling the Europe-based OCGs is the lack of insight European, including UK, governments and taskforces have into Vietnamese culture.

Unlike in America and Australia, there has been very little integration of the Vietnamese diaspora into front line services dealing with the issue.

It should also be recognised that while the OCGs running the Hanoi – UK routes are Vietnamese-ethnicity, they are EU nationals.

To help connect with the diaspora communities, countries need to be proactive in recruiting Vietnamese-ethnicity nationals into their police forces, charities and NGOs.

Mimi said: “It will take a multi-state, multi-stakeholder effort and you have to involve Vietnam in this because they speak the language and know the culture.

“The European governments don’t know how to deal with Vietnamese people, the Vietnamese diaspora communities or Vietnamese criminal elements.”

The lack of integration helps explain the huge disparity between the number of victims recorded in the National Reference Mechanism (NRM) and the number seen by those working in the community.

The East and Southeast Asian Scotland (ESAS) charity called the NRM figures “grossly underestimated”.

Since the outbreak of Covid-19 last year, ESAS has come into contact with 250-300 victims from across Scotland and have directly helped 170 people and families.

Kimi Jolly, founder of ESAS, believes the NRM fails to recognise some of the challenges faced by trafficking victims after they are reported to the system.

It doesn’t account for the debt-bond owed to the traffickers and the very real dangers they and their families face if it’s not paid back.

When trafficking victims enter the NRM system often their ability to work is removed.

Kimi explains: “When you arrest someone or take someone into care, you are not just taking that one person – you are taking their whole family back in Vietnam into care.

“You are pausing their ability to repay back their loan sharks.

“This is a real problem.”

‘Threatened with death’

The threats posed by traffickers are very real for a victim’s family in Vietnam.

If a trafficked person is taken into a system that doesn’t allow them to work, traffickers will kidnap and enslave their loved ones.

“If these people don’t pay then they threaten to kill their family members or take their daughter,” says Kimi.

“They will find a way to get money from you.

“There is a genuine danger.

“There are people who leave children back in Vietnam that are being threatened with death.”

This inability to pay off debts within the NRM system may be one of the reasons why so many Vietnamese people have been reported missing in Scotland in the early part of 2021.

Trafficking in Vietnam

The victims of human trafficking that are being found in Scotland all begin their journey as willing participants who want to be smuggled into the UK.

In Vietnam the picture is very different – victims are young women and girls who are being trafficked from rural villages into China for forced marriages.

Blue Dragon is rescuing around 200 victims a year from China but believes thousands are never recovered.

The majority of victims are under the age of 25. A quarter of them are children.

Are you a victim of human trafficking or modern slavery in Scotland? Have you witnessed it in your area? Call the Modern Slavery Helpline on 08000 121 700. Or call Police Scotland on 101 or 999 in an emergency.

If you would like to speak to our Impact investigations team please email Dale.Haslam@ajl.co.uk

The Exploited

The Exploited is a special investigation exposing the hidden prevalence of human trafficking and modern slavery in our local communities. Across rural Perthshire and the Highlands to urban Aberdeen and Dundee – victims, and their abusers – are hiding in plain sight.

Read the full series:

- Young mother raped daily in Perth flat after being trafficked across Europe

- Trafficked women brought to Aberdeen and Inverness and sold online for sex

- London teenagers forced to smuggle drugs into Inverness by organised crime gangs

- Man injured after being forced to work at Aberdeen construction site with no pay

Credits

- Words by Sean O’Neil

- Design by Cheryl Livingstone

- Illustrations and graphics by Roddie Reid

- Data visualisations by Lesley-Anne Kelly

- Videos and photography by Drew Farrell, Steve Brown and Blair Dingwall