Having your personal VIP lounge at a major airport would purely be the preserve of the super rich or powerful today – but in the 19th century, Highland lairds had their own equivalent.

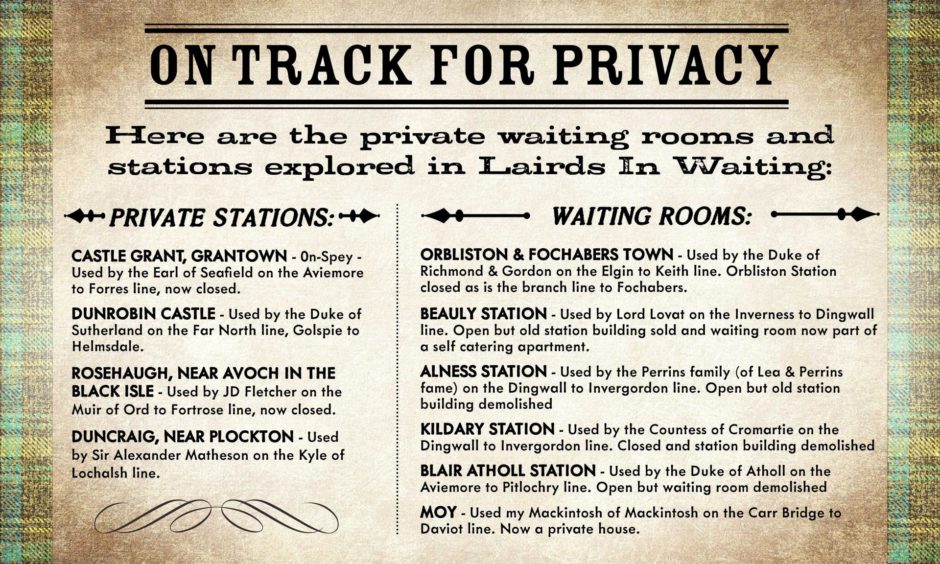

These were the private waiting rooms – in some cases entire stations – on the Highland Railway, given as favours to the local landed gentry for allowing the line to pass through their land.

Not that the landowners were reluctant to see the arrival of the Highland Railway, which saw lines snaking out from Perth to reach Caithness in the north, Fochabers in the east and Kyle of Lochalsh in the west, bringing the Highlands into the existing network.

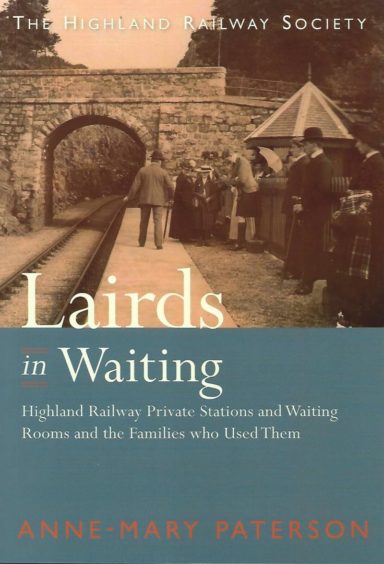

The lairds were businessmen as much as landowners and saw and wanted the benefits the railway would bring from the 1850s on, said Anne-Mary Paterson, author of a new book, Laird In Waiting, which tells the stories of these private waiting rooms and the families who used them.

“The railways were so late in coming to the Highlands because of all the engineering problems, and the Highlands were really a bit backwards in comparison to other places and had terrible roads and so on,” she said.

Catching up with rest of the country

“So most of the landlords were very keen on the railways coming, because they saw it as catching up with the rest of the country.”

Not all the landlords, many of them becoming directors of the Highland Railway, asked for private stations, but quite a few did, to be used by themselves and their families and guests, as they were linked to the rest of the country.

“Of course, Queen Victoria had her private waiting room at Ballater Station, so maybe it was a kind of fashion,” said Anne-Mary.

“They were used by the directors and the people who visited them and any grand people who came. The Emperor of Japan visited the Duke of Atholl and he would have used the private waiting room, at Blair Atholl. It was a bit like the VIP lounges you have at an airport nowadays.”

Anne-Mary said each of these waiting rooms would have been equipped with comfort, such as a fireplace to keep guests warm as they waited for the arrival of their train.

Her book, published recently by the Highland Railway Society, looks at each of the private facilities, the families who owned them and the impact the arrival of rail had on the communities around them.

Probably the best-known private station which celebrated its 150th anniversary in 2020, is Dunrobin Castle on the Far North Line, built for the 3rd Duke of Sutherland. It is still open when the castle is open to the public.

“They all have very interesting stories attached to them, but I suppose Dunrobin is one of the most interesting,” said Anne-Mary.

Duke who built railway engines

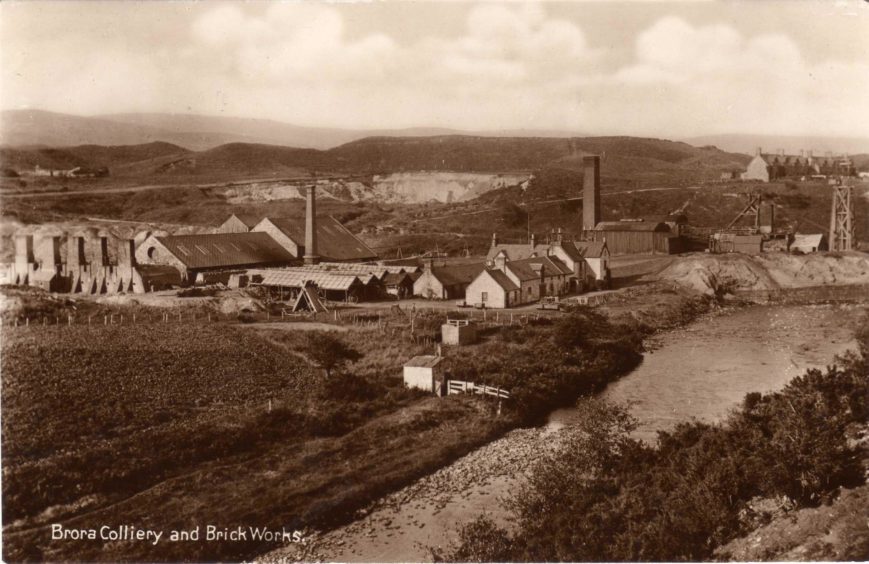

“There was a coal mine at Brora and it closed in the earlier part of the 19th century because it wasn’t profitable and the 1st Duke of Sutherland closed it. When the railway arrived, the 3rd Duke reopened the mine. He was very interested in railways and had some training in railway engineering.

“He had a workshop, where the tweed mill eventually was, and he did all sorts of things in there, including building engines. So he reopened the coalmine, and there was also a brickworks next to them. He built a track from them so he could export the coal and everyone in Brora could have coal.

“However, it did have a high sulphur content, so it was a bit smelly.”

Anne-Mary added an earlier Duke of Sutherland had opened a whisky distillery and the arrival of rail meant its new owners could export more and expand.

“There were real developments which came with the Highland Railway,” said Anne-Mary. “It wasn’t just the coalmine and brickworks at Brora. Near Moy Station is the Tomatin Distillery. It opened in 1898 when the direct line from Aviemore to Inverness opened.

“It really opened up the Highlands and it became fashionable as well, because of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert coming to Balmoral.”

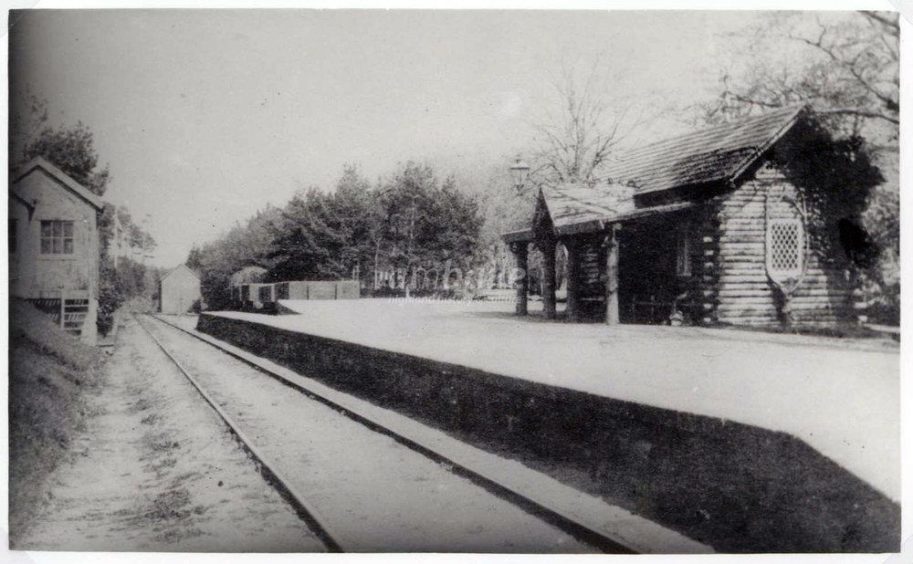

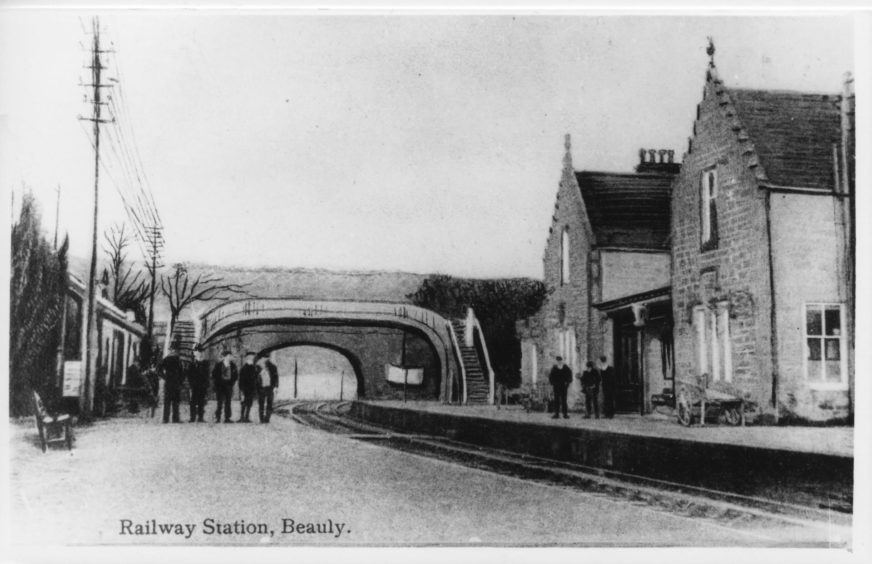

Anne-Mary’s interest in these private waiting rooms was sparked by her local station, Beauly, where Lord Lovat had a private waiting room.

“The new platform is across the line from the old station, so when you are standing on the platform you are looking over to the old building and the waiting room is an extra wing,” she said. “Above the door, there used to be a place where they put the Fraser crest. That gave me the idea. I don’t think anyone has written on the subject before.”

Railways run in the family

Anne-Mary has a family connection to the entire line. She is a great-grandniece of Murdoch Paterson, Chief Engineer of the Highland Railway and his brother, William who was also involved with the design and construction of railways radiating from Inverness.

“My father was also a civil engineer on the railway, so I have been brought up in that line,” said Anne-Mary, who wrote Pioneers Of The Highland Tracks, a biography of William and Murdoch Paterson, and also penned Spanning The Gaps, about Highland railway bridges and viaducts and the stories connected with them.

She hopes Lairds In Waiting will offer readers a glimpse into an almost forgotten age.

“I hope people will have an interest in the stories connected to all these private waiting rooms and stations, but will also realise how important the railway was in the whole development of the Highlands and Great Britain.”

Copies of Lairds In Waiting are available from the Highland Railway Society at www.hrsoc.org.uk