Thanks to the ARCHIE Foundation and generous donations from pupils in the north-east, Uganda has its first children’s operating theatre.

Ashleigh Barbour travelled to the country to witness the conditions that families have to contend with during the most worrying times of their lives

Have you ever been packed inside a London tube in rush hour on a hot, clammy day?

As the temperature rises and commuters press in, it’s a relief when you can finally escape the tunnel for some air.

Walking through the crammed corridors of Uganda’s Mulago Hospital, it’s the closest comparison that comes to mind.

Anxious face after anxious face lines the walls, as crowds of needy patients huddle in the open waiting areas with every ailment you can imagine.

Families who are staying close to loved ones in the hospital either sleep on the cold, hard floors on thin sheets or under the stars in the dusty courtyard outside.

They wait, and they wait and they wait, surely wishing they were anywhere but here.

We have joined them at Uganda’s main hospital as part of our trip with the ARCHIE Foundation to open the country’s first ever children’s operating theatre.

Until now, Uganda has had just five theatres to deal with its 40 million population – including 22 million youngsters.

ARCHIE’s new theatre, paid for by generous donations from north-east children, was originally supposed to be built here so it could be close to the others.

However, the Ugandan government announced it would be renovating the building, leaving no space, and ARCHIE moved the project to nearby Nuguru Hospital.

The setback caused many sleepless nights for the team behind the scheme, but I for one am relieved the theatre was not built here – this is no place for a child.

Mulago is one of the busiest hospitals known to man – and home to the busiest maternity ward in the world.

The general hospital has an official capacity of 1,790, although it often takes in more than 3,000 patients at any time.

Last year, more than 30,000 babies were delivered here as the labour ward attended to an average of 80-100 mothers every day. The rate is more than three times that of the busiest hospital’s in London.

The ward for premature babies is filled to capacity with rows and rows of metal cribs holding tiny bundles crying out for their mothers.

I am told that when the nurses run out of incubator space, they place the babies on plastic chairs. When they run out of chairs, the babies are placed on the floor.

Three newborns have been packed onto an abandoned operating table because there are no suitable beds left, while other tots are placed in between paperwork and equipment.

Three babies born to three different mothers have been placed side-by-side in one incubator, the forms detailing which newborn belongs to which woman sitting precariously on top.

One infant is so premature it is difficult to comprehend how she is still alive in these conditions.

Laid in an incubator with a plumper, sleeping baby, the tiny scrap is kicking her matchstick legs ferociously and punching her curled-up fists in the air. She is literally fighting for her life.

I ask our guide, paediatric surgeon, Dr Kakembo Nassar, if the little girl will survive.

“Of course – she will be fine,” he says.

“She will be home by next week.”

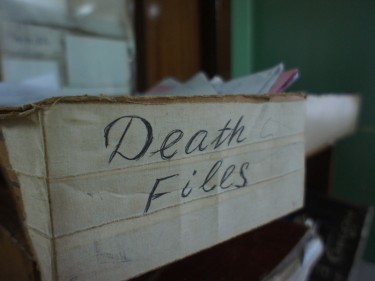

Not all of the young patients will be so lucky. On a nearby desk, an ominous box labelled “death file” contains a wad of paperwork recording the babies who have perished so far this week.

A nurse adds another couple of forms to the pile while we are there.

As we leave the tiny newborns behind, we come across a young mother who has just given birth to four babies, two of which are conjoined.

The woman is on her own, but this comes as no surprise to anybody.

David Tipping, projects director of ARCHIE, who has visited the country numerous times while setting up the theatre, recalls a mother he met during his last trip.

The mother was sitting patiently, waiting for her baby to have surgery to remove a massive growth on his head.

“She had the saddest face I have ever seen, and understandably so,” said Mr Tipping.

“But it turned out to be so much more – her husband had left her as the child had a deformity.

“These babies bring shame on families, so the father ups and leaves.

“Not only does this new mother have to look after a baby who is ill, she will have to do it on her own. She probably has no money and no place to stay.

“It’s tragic.”

We are taken down to the main children’s ward, where more than 60 youngsters are awaiting surgery.

One little boy is in the queue for an operation to remove a tumour in his stomach, while another baby has been born with his intestines growing outside his body.

Our last stop at Mulago is to finally see the five theatres I have heard so much about.

They are situated in the depths of the hospital, joined by an ominous corridor, and I try to hold back tears as I imagine a small, scared child being wheeled down here for surgery.

The rooms are dim and foreboding, and the grim reality of the situation that the skilled medics have to deal with here is overwhelming.

I would trust any of these extraordinary surgeons with my life – but as an adult, the thought of having an operation here terrifies me.

As we leave Mulago Hospital and its revolving door of patients, a torrential rainstorm begins to hammer down and it starts to feel a little more like home.

But behind us is a place – and a healthcare system – that is worlds apart from ours.

“It’s not until you’ve seen this that you can begin to understand what people here have to live with here,” says David Cunningham, ARCHIE’s chief executive.

“In saying this, you don’t hear anyone moaning or causing a fuss. It’s all they know.”