It’s one of the world’s most instantly-recognisable sights.

And the Sydney Harbour Bridge has attracted admiring glances from millions of visitors to Australia ever since it was opened nearly 90 years ago in 1932.

Tyne Bridge design

The iconic structure was built by British firm Dorman Long of Middlesbrough, who based the design on its 1928 Tyne Bridge in Newcastle.

But few will be aware of the significant impact which a group of redoubtable north-east men had on the ambitious construction scheme, whether in working with the granite which decorated the bridge or establishing a little part of Scotland in the Southern Hemisphere after travelling there from all parts of Aberdeen and Aberdeenshire to become involved in creating one of the globe’s great engineering feats.

The Press & Journal reported in 1926 that dozens of men had left their roots in Scotland to embark on the arduous trek Down Under – a journey which could last months and often required passengers to undertake treacherous voyages on tempest-strewn seas.

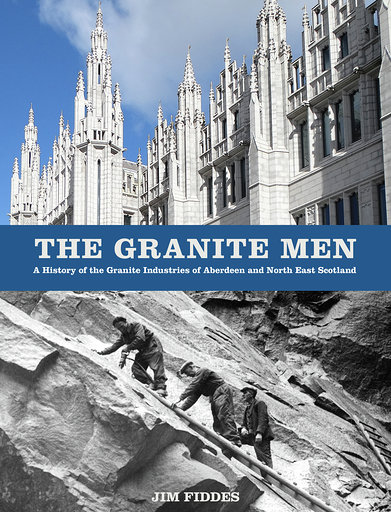

The Granite Men

Jim Fiddes, author of The Granite Men, who has examined the history of the rock which has become synonymous with Aberdeen, discovered that hundreds of workers throughout the industry had expressed interest in joining the Harbour Bridge adventure when an agent from Dorman Long visited the city.

The company had previously appointed John Gilmore, a far-travelled son of Harthill in Kintore, who had worked in quarries at Kemnay, Rubislaw, Peterhead, Brechin and Ailsa Craig – in addition to plying his trade in the United States – to manage the granite facility at Moruya, 200 miles south of Sydney.

It was the start of one of the trailblazing chapters for which Scots have become famous.

Mr Fiddes said: “The Aberdeen granite industry might have been in decline after the First World War, but the expertise of its workers was still in high demand.

“It was in December 1926 that the Press & Journal reported that, earlier that year, 30 men had left the city to work on the Sydney Harbour Bridge.

“The paper noted that letters sent home from the men indicated they were more than happy with their working conditions – and that the wage they had signed up to had already been increased by 10 shillings a week.

“When a representative from Dorman Long came to Aberdeen, he received almost 250 application forms and the first party of workers from the north-east left Aberdeen in February 1926 with another group following them in May.

“Unlike most of the granite men who had previously gone to work in North America, this group took their families with them and children were born in Australia, who later moved back to Scotland with their parents.”

Mr Gilmore was a steely character, somebody who had embraced all manner of challenges during his peripatetic life and he responded to his new role in Sydney with the same purposeful resilience which had caught the attention of his new employers.

United nations

As the scale of the bridge project grew, people of 13 different nationalities ended up working at the site and carried out a variety of roles, with the majority fulfilling the positions of stonemasons, quarrymen and labourers.

Mr Fiddes added: “Gilmore took his wife, son and eight daughters on the seven-week voyage.

“For all the north-east men who decided to set sail to Australia, the initial contract was for three years with the possibility of further work beyond that.

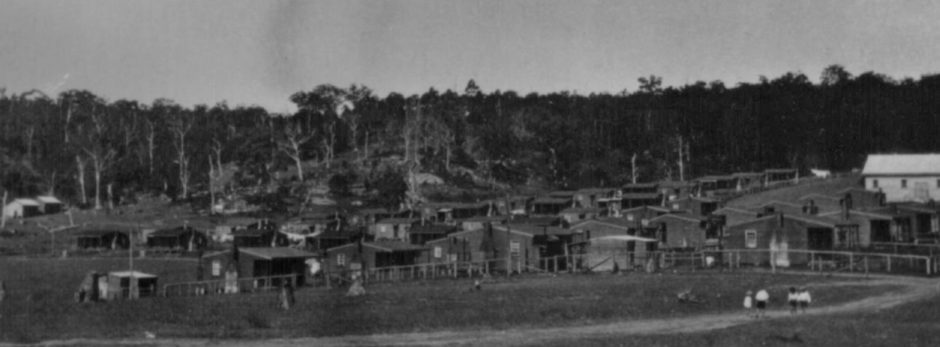

“In the community known as Granite Town that grew up at the quarry – which consisted of simple houses, bachelor’s quarters, a post office, a store, a hall and a school – they were joined by Australian and Italian stonemasons.

“At the peak of the work, the population at Granite Town reached 300.”

The Scots found themselves immersed in gruelling labour in often hazardous conditions, but, with job alternatives scarce back home, most of them persevered and one later looked back on his endeavours and said: “We never dreamed we would work on something like this when we were growing up in the Mearns.”

Mr Fiddes said: “The granite these men worked on was used for the four impressive 89-metre-high pylons, but the pylons are actually constructed from concrete, while the granite, 17,000 cubic metres of it, was used to face them.

“In addition, the pylons are an architectural feature and not a structural one.”

That hasn’t diminished their majesty as the years have passed.

The granite industry really shone throughout the 19th century

There’s no underestimating the significant contribution of quarries to the north-east economy, nor the impact which they made on so many communities across the region.

Jim Fiddes analysed how the original sites increased rapidly in number as they received more orders and commissions from all over the world.

He said: “Granite made a significant contribution to the economy of Aberdeen. At the beginning of the 20th century, there were around 1,000 men employed in the building sector. There were also around 100 monumental and polishing yards, all different sizes employing around 1,200 men in total.

“The numerous quarries of the north-east also employed several thousand men, quarriers and settmakers amongst them. In addition, there were ancillary occupations associated with the industry such as blacksmiths and carters.

“But perhaps more important than the purely economic side was that granite created the built environment of Aberdeen, the way it looked as we can see all around us today, and how it was viewed on the national and international stage.”

He added: “In researching for the book, I tried to find out when Aberdeen became known as the Granite City.

“The Bon Accord Repository of 1842 described it as ‘the Marble City’.

“But, shortly afterwards, it seems to have begun to be called the Granite City, both by its citizens, but also by newspapers and writers elsewhere in Britain and the world.

“Granite had been used to pave the streets of London from as early as 1760. From the end of the 18th century, it was used in major civil engineering projects such as harbours, lighthouses and then bridges such as London Bridge.

“Following the development of polishing, it began to be used for gravestones and monuments as any visit to The Necropolis in Glasgow will testify.

“Two Aberdeen yards, Macdonald’s and Wright’s, both exhibited at the Great Exhibition in London in 1851.

“And then, two years later, the author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin – Harriet Beecher Stowe – visited Macdonald’s yard in Constitution Street and commented, in a letter to her brother, that there were many Aberdeen granite monuments to be seen in America, even at that early date.

“Queen Victoria chose a massive block of Cairngall granite for the sarcophagus to house her beloved Prince Albert and later it would also house her remains.”

How the granite men’s labours became an international phenomenon

Aberdeen monuments were sent all over the world, to France, China, Australia and, above all, to America as the 19th century advanced.

In 1877, Heslop & Wilson in Peterhead exported a structure which became known as the Lick Monument to Fredericksburg in Pennsylvania.

It was 30 feet high, weighted 95 tons and cost around £170,000 in today’s money.

Aberdeen and the surrounding communities also proved the launch pad for many men to travel to America in significant numbers and they created state capitols, banks, bridges and a range of other prestigious buildings which still exist today.

Mr Fiddes said: “They also helped establish the American granite industry especially in the states of New England, Barre in Vermont being one major example.

“Some of them built their own life and businesses in America, but a lot came back and used money they had made there to set up their own granite yards back in Aberdeen.

“One example I found was of a man who sent money back to his wife in Aberdeen and, unknown to him, she saved enough money for him to open his own yard when he returned for good.

“Aberdeen men also went to Russia and South Africa and, even as late as the 1920s, a group went to Australia to work on the Sydney Harbour Bridge.

“Granite gave Aberdeen an identity on the world stage.

“There are several cities built using granite, but there is only one Granite City.”

Jim Fiddes chooses his cream of the crop in Aberdeen

“I have three favourite granite buildings in the city,” he said.

“Firstly, there is the art gallery.

“I like its relative simplicity in the decoration which I think suits granite. I also like the use of contrasting Kemnay grey and Corrennie pink stone.

“Secondly, there is Rubislaw House at 50 Queen’s Road, which is a house that divides opinion in Aberdeen.

“Built in the 1880s for the great master mason John Morgan, it was designed by his architect friend John Bridgeford Pirie (the pair also built Queen’s Cross Church and large parts of Hamilton Place). There are many fine granite mansion houses in Aberdeen but nothing quite like Number 50.

“Finally, on a completely different scale, I think the humble Saltoun Arms on a corner site between Frederick Street and Wales Street, is a charming little granite building.

“It uses granite from Persley and Dyce and its two polished columns of Rubislaw stone show just how far the industry had come at the time it was built in 1896.

“In the 1820s and 1830s, only vast prestigious buildings could afford polished granite, and even the British Museum couldn’t afford all the columns that it wanted.

“But, by the end of the 19th century, a humble bar could have them.”

The Granite Men has been published by The History Press.

Further information is available at https://www.thehistorypress.co.uk/