Think of a magician who walks up to strangers, astounds them as money appears from nowhere, then just strolls away. You might conjure up an image of Dynamo working the streets of London.

Think again… this master illusionist was at his height more than 180 years ago and he was casting his spell on simple peat cutters at Brig o’ Potarch.

John Henry Anderson astonished the workmen as they toiled, by picking up a piece of peat, breaking it open and having a silver sixpence roll out. He did it again and this time a shilling was nestling there. He then asked to dig his own piece of peat from the ground and inside was a glowing, golden guinea.

Anderson left the bemused Victorian workmen with their treasure trove and simply walked away. He was sure in the knowledge they would spread the word far and wide they had just seen the Great Wizard of the North work a miracle … ahead of his run of shows in Banchory.

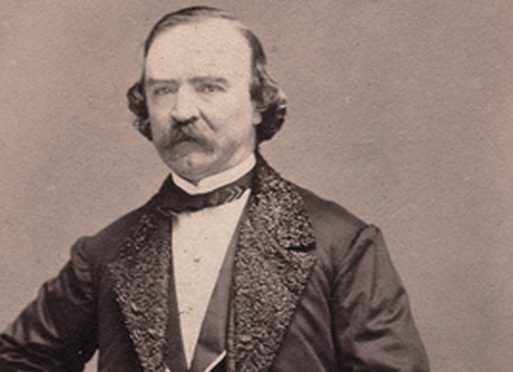

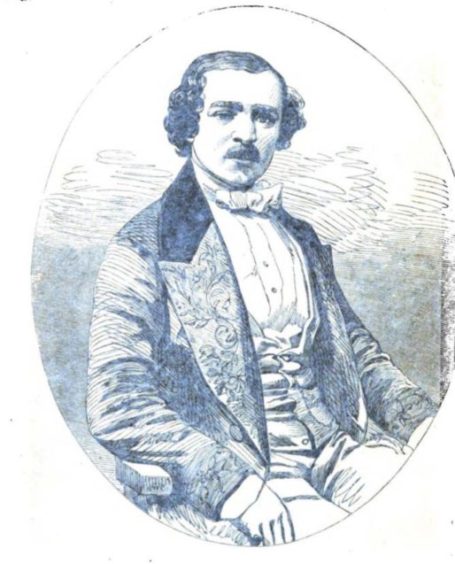

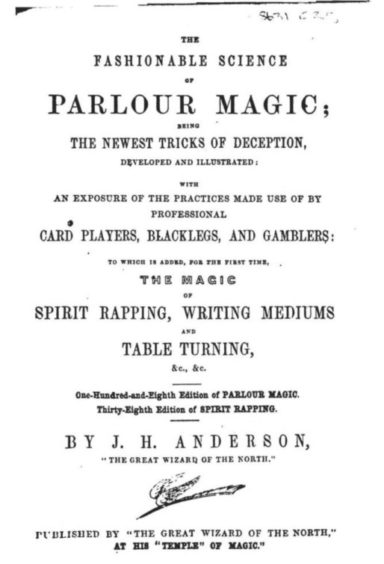

This was the real magic of Anderson – a consummate showman who brought the skill of illusion and wonder out of the hands of wandering showmen and into Victorian theatres, with a never-before-seen flair for self-publicity.

He is credited with being the first magician to pull a rabbit from a hat, the man who brought the astounding linking rings trick from China, who performed for Queen Victoria, toured the world and became one of the fathers of modern stage magic.

Although he was accused of being in league with the devil on the way.

Not bad for a north-east loon, born a cottar’s son just outside Kincardine O’Neil.

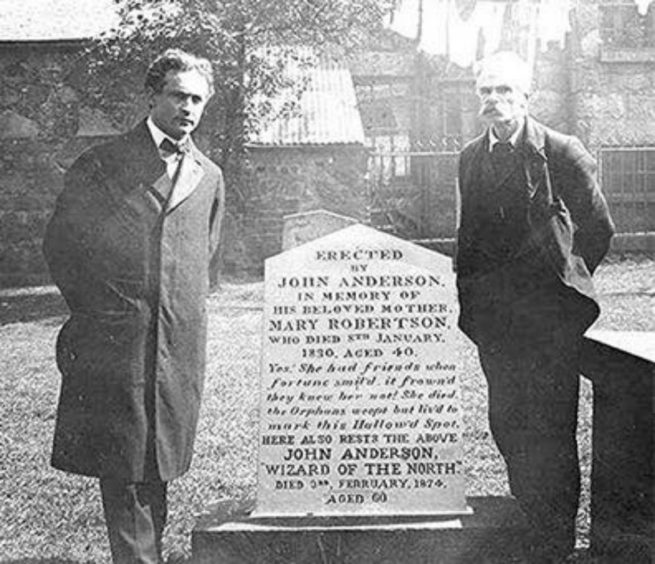

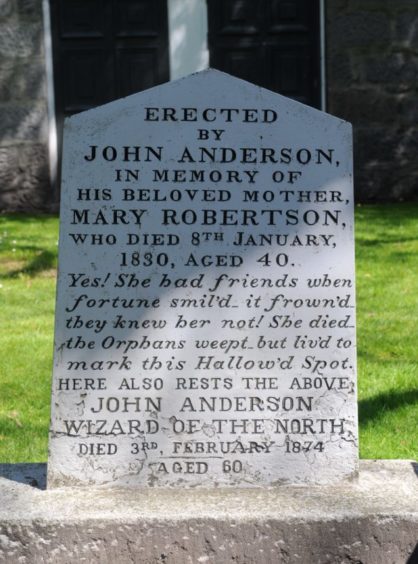

And today, Aberdeen-based magician and escapologist Dave Goulding wants to keep alive the memory of a man who, among other things, was revered by Harry Houdini. So much so that when the legendary American escapologist and magician performed in the Granite City in 1909, he visited Anderson’s grave in St Nicholas Churchyard.

“Among magicians he is known and every few years interest in him in Aberdeen kicks off,” said Dave, who along with other members of the Aberdeen Magical Society still tend and maintain Anderson’s grave.

“It was a long time ago and times have changed, but is he well enough known in Aberdeen as a local hero? No I don’t think he is,” said Dave, a trained mathematician who works in IT.

This year marks the 190th anniversary of Anderson entering the world of entertainment – but not as a magician. He joined a travelling dramatic company touring Scotland.

“He was going to be a blacksmith at first, but didn’t fancy that so joined a troupe of actors,” said Dave.

While in Aberdeen he saw a conjurer and decided this was to be his future career, one which would lead to him being dubbed the Great Wizard of the North by no less than Sir Walter Scott.

In his early days, he came under the wing of a local magician, Scott, who had Scottie’s Show in Aberdeen’s John Street, on the site of the former St George’s In The West Church.

As his talent flourished so did his reputation – not always for the best. While booking lodgings in Forres, the elderly landlady saw his umbrella inscribed with The Wizard of the North and had hysterics.

She screamed at him: “Ye’re the De’il himsel’. I smell brimstone aff ye an’ ma bleed is rinnin’ caul.”

Then she fainted and cut her face as she fell, leading to wild rumours of murder and robbery as neighbours gathered to see what all the shouting was about. Anderson ended up spending a night in the police cells before being released. Free to go – and also with plenty of free publicity that sent people flocking to see his show in Elgin.

It was to be a theme for Anderson, said Dave.

“He is important in the history of magic, first and foremost because of his publicity stunts. He was the first to do that, the first to say ‘hey, look at me’. That’s what really influenced Houdini and that’s how Houdini got interested in him.”

Prior to Anderson, publicity was all about putting up posters or depending on word-of-mouth about your magic act.

“Anderson went out and did stuff,” said Dave. “If he went to a city he would have chaps carrying placards up and down the street. He bumped into a circus owner once in America and said ‘how about you do a parade through the city on your way to the circus site’. They shared the publicity, so his name was on the sides of elephants marching up and down the high street.”

Wherever he went

he would make coins

appear magically

The illusionist even went as far as having butter moulds made bearing his name and giving them to hotels in towns where he was appearing.

“It meant that the butter would go on the table and everyone would go down for breakfast and say ‘oh, Anderson is performing tonight at the Hippodrome’.

“He would do stunts all through his life. Wherever he went he would make coins appear magically,” said Dave, citing the peat cutters at Potarch.

“Once he saw a lad fishing on the Thames and asked to borrow his fishing rod. He reeled in a fish straight away, they opened the fish up and tucked behind its gills was a sovereign. That sort of thing would get people talking.”

Which is the sort of thing Dynamo does in 2020. “That’s maybe not a bad parallel except Anderson was doing throwaway tricks to get attention and publicity, for Dynamo it’s a career.”

Dave said that Anderson was hugely theatrical in his performances, building on his acting background.

“He wouldn’t just pluck a coin out of the air and say ‘there’s a coin’. There would a big build up, a great big presentation. It was wonderful, it was elegant. He was also very modern. He was new, he was inventive and stuff people hadn’t seen before.”

That included introducing the linking rings trick from China, which is still performed today.

“And they do say it was either him or a French magician who first did the rabbit out the hat, although most people credit Anderson.”

Another of his most famous tricks, still popular now is the inexhaustible bottle, where a magician pours any chosen liquid from a container.

But Anderson, who performed for the Russian Czar as well as Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, suffered ups and downs throughout his career.

In 1845 he financed the City Theatre, built on Glasgow Green, but four months after it opened it was destroyed in a fire. He picked himself up, borrowed money and toured across Europe before conquering America with 100 successive shows at the Broadway Theatre.

With his fortunes on the up again, he leased London’s Covent Garden Theatre in 1856 – only to see his career go up in smoke for a second time. Fire caused by a gas leak reduced the building to a smouldering shell – and Anderson was ruined again.

He is a magic hero. He was

one of the three proper guys …

who took magic onto the stage

and made it glamourous.”

By now his career was waning although a farewell visit to Aberdeen saw him packing the Music Hall for a month. But that was the beginning of the end, he was bankrupt by 1866 and died in poverty in 1874 – the year Houdini was born. He left just enough money to be buried beside his mother in St Nicholas Kirkyard.

Yet he was still held in high esteem in his native north-east, with large crowds gathering on Union Street for his funeral procession as the Great Wizard of the North took his final bow.

It was a respect Harry Houdini shared.

Dave said: “When Houdini came to Aberdeen, he went to see his grave, had photos taken and met some of Anderson’s family. Even before he came here he spoke of his admiration for Anderson.”

And Dave shares that view.

“He is a magic hero. He was one of the three proper guys – along with Frenchmen Jean-Eugene Robert-Houdin and Austrian Louis Dobler – who took magic onto the stage and made it glamorous rather than a trampy troubadour in furs doing street magic. They made it respectable.”