Aberdeen Railway Station is on track to a bright future with an £8 million transformation on the way… but once it didn’t have a future at all. It might never even have been built.

Instead, there could have been a circular rail route carving through the heart of Aberdeen – “like an earthwork around a besieged city” – had controversial proposals succeeded at the dawn of train travel in the Granite City.

This circuitous route, dubbed the Circumbendibus by its opponents, would have joined the city’s then disconnected north and south rail lines by, literally, going all round the houses. It was an idea that set off a storm of protest over the winter of 1862.

Railway historian Keith Jones said: “This was the Union Terrace Gardens controversy and Marischal Square row of the 19th century – with the intrigue of the railway director also being on the council and supporting the development while all the good residents in the suburbs of Aberdeen were against it.”

At the time, the rail line from the north terminated at Waterloo Quay, going via Kittybrewster, while the southbound line had its station at Guild Street. The only way for passengers to connect was to walk between the two, often missing the frequently unpunctual trains, prompting unscheduled and unpopular stopovers in Aberdeen.

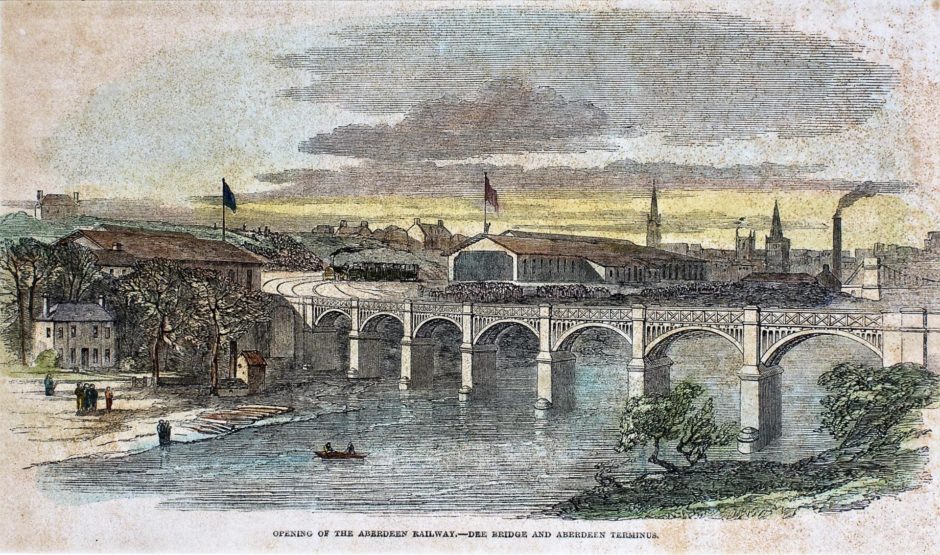

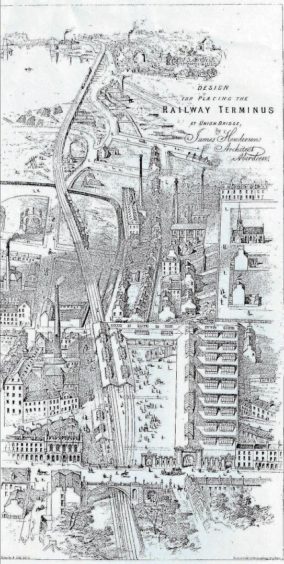

Various solutions were mooted among train companies of the time, including joining the north and south lines via the Denburn Valley to a new unified station, as it is today. But there was deemed insufficient capital, despite this having been mooted as an idea some 22 years earlier, when architect James Henderson drew up plans for a train terminus on the site of the present station.

The Scottish North Eastern Railway company then proposed connecting north and south with a line from near Stonehaven to Kintore – bypassing Aberdeen altogether and causing huge consternation among the city’s businessmen and politicians.

Which was when the Great North of Scotland Railway dropped the Circumbendibus into the mix. It was a satirical name – Latin for “roundabout way” – for the project that stuck for all time.

There was a huge

hoo-ha in the

city over the

circumbendibus railway.”

Keith said: “This was a proposed line to connect the two (north and south routes). It would have come off the line at Kittybrewster then in a fairly tight circle round the city would have come through Rosemount and the top end of Carden Place, through Ferryhill then turning round to connect with the south terminal at Guild Street.

“There was a huge hoo-ha in the city over the Circumbendibus railway,” said Keith, a member of the Great North of Scotland Railway Association.

Little wonder, given the route would have crisscrossed streets like Holburn Street, Hutcheon Street and Carden Place.

The council provost of the time, Alexander Anderson, was also a director and secretary of the Great North. He was roundly abused by outraged Aberdonians, suggesting he would be lining his own pockets as the proposed line was to run through land he owned.

More than 3,500 signatures to a petition against the plan were gathered in just four days.

The Aberdeen Journal of December 10 1862 carried a notice for a public meeting for all opposed to “adoption of so indirect, inconvenient a route”.

The notice went on to call the line: “An unsightly ditch surrounding the whole suburbs from Hutcheon Street to Clayhills, up to 23 feet deep and 40 to 100 feet wide.

“The whole thing would look like an earthwork around a besieged city”.

A report on the public meeting itself described tumultuous scenes of jeering and hissing at the mention of the provost and cheers when speakers said there was “no excuse for the provost betraying the interests of the citizens”.

Keith said: “Railways were governed by Acts of Parliament and this was quite heavily fought in parliament. So at the end of the day, there was a deal done and money was found to build the line from Kittybrewster through the tunnels at Woolmanhill and into a new Joint Station, which was opened in 1867.”

And so dawned a new era, with rail lines north and south brought together in the Joint Station at the heart of the Granite City.

“It connected the north-east of Scotland to the rest of the country,” said Keith.

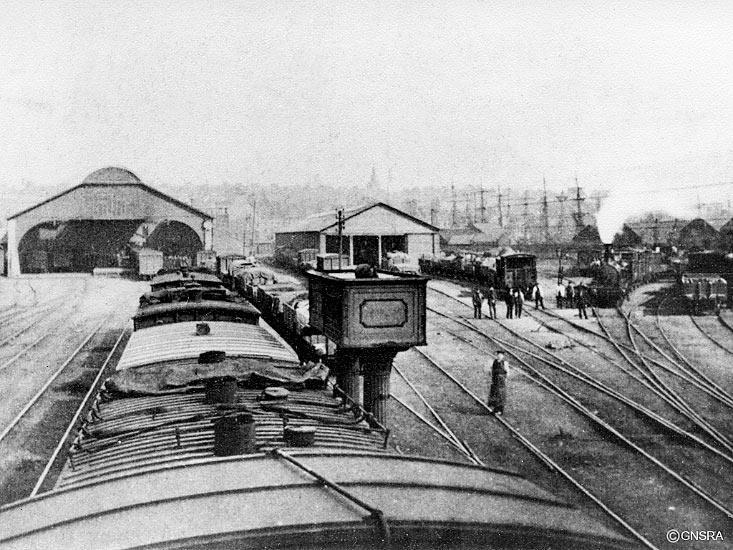

The first Joint Station – with its limited platform and concourse space – might have revolutionised train travel in Aberdeen, but over the years it became unfit for purpose in the Golden Age of Steam.

“From the 1890s onward it was really becoming inadequate for the traffic. The concourse was crowded and people trying to get on trains had to navigate along barrel-loads of fish, which made the place rather smelly,” said Keith.

“It was also said to attract undesirables, so from the 1890s onward there were lots of angry press reports about how Aberdeen was being let down by the state of the existing railway station.”

One letter to the P&J in 1910 from an Aberdonian returning from London, spoke of the glazed western canopy having “as many holes as windows… where the panes of glass themselves are things of shreds and patches”.

The letter writer, who said he had travelled by train extensively across the country, said: “The station, I do not hesitate to say, is a disgrace to a city of the position and importance of Aberdeen.”

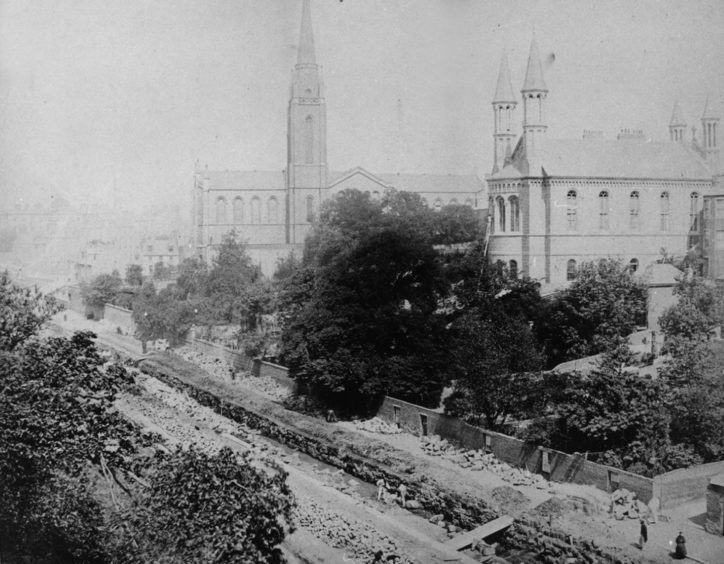

The rebuke – along with many others – seemed to hit home and in 1912 work began to completely demolish the old station and build a brand new one in its place – all while trains were still running into the platforms.

“Perhaps today health and safety would have taken umbrage to how it was done,” said Keith.

“Effectively there was a huge rolling platform which they built which straddled several tracks. It was like a giant scaffolding and it rolled down as they took down the old station, then rolled the other direction as they built the new roof. It was quite the engineering feat in its day.

At the same time the number of platforms and passenger accommodation was transformed and increased, with a huge central booking office, a cafeteria, plus offices for the plethora of railway companies as well as staff and telegraph accommodation.

Most of this was beneath an impressive glass and steel roof over the concourse which was 247ft long and 97ft wide.

When it opened in

1915 it was the most

modern railway

station in the country.”

When it opened in 1915 it was the most modern railway station in the country, serving not just the cross-country services but the extensive network of suburban and commuter trains steaming in and out of Aberdeen and further afield to Buchan and Deeside.

The station, opened 105 years ago, is the one which stands to this day. It survived two world wars – although all the glass in the roof was removed and stored beneath the platforms at Fyvie Station between 1940 and 1945. It also lived through the Beeching cuts of the 1960s that saw train services in the north-east all but eradicated.

“The next big change was in the 70s,” said Keith. “After Beeching the operating area was drastically reduced in size. They took out the north-facing platforms. Over the next few years the offices at Guild Street were built over the railway and then the Trinity Centre was built. In the station, they built what they called a travel centre and got rid of the old wooden booking office, which had been a feature.”

The most recent change wrought was by the arrival of Union Square in 2009 which brought the frontage of the station indoors as part of the shopping centre’s main concourse.

Keith said the latest £8 million revamp of the station, with work due to start this year, is very much a case of evolution, not revolution. It also has some echoes of the Joint Station’s past, with the plans including changes to shops and glass-fronted restaurants on the concourse.

“The designs I have seen seem sensitive to the 1915 design. If you look back at old photographs of the station there were lots of little kiosks around the concourse in the 1960s and 70s, like a fruiterer and old-style newsagent. So this is just evolution.”

Keith believes the station has been crucial to the life of Aberdeen.

“Because of where it is, which is very central, it has acted as a focus for travel. Up to the coming of modern aircraft, all long-distance travel tended to be by rail. Politicians, people performing at the theatre would have come in by train,” he said.

“It played a major part in Aberdeen for travel, holidays and commerce right through the years.”

And he believes there is a bright future for Aberdeen Railway Station and train transport, citing a growth in the number of train services, plus increasing use of rail.

“There are probably more people using the station than perhaps even going back to the pre-First World War days.

“Of course coronavirus has changed everything, but there has been an increasing use of public transport. Hopefully once we get over telling people not to use public transport it will pick up again.”