It’s an event which brought death and devastation to so many families across the north of Scotland; the surrender of the 51st Highland Division at St Valery-en-Caux on June 12 1940.

Few communities were left unscathed when thousands of young men were either killed during a desperate last stand at the little French village or were captured and forced to spend years in prisoner of war camps.

Remarkable story

There were precious few positive outcomes for the troops involved in the campaign.

And yet, the remarkable story of Malcolm Straughan, who escaped from the Germans in 1940, then was part of the forces who reclaimed St Valery four years later and subsequently won the Military Medal for his courage deserves a wider audience ahead of the 80th anniversary of Scotland’s commemorations to the 51st.

Mr Straughan, who joined the Gordon Highlanders as a regular soldier in 1932, aged 18, undertook his training at Castlehill Barracks in Aberdeen.

He was with the 1st Battalion Gordon Highlanders when war was declared in September 1939 and he and his comrades were mobilised immediately and journeyed to France as part of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF).

They landed at Cherbourg on September 23 and stayed there for the period of the “phoney war” until the Germans launched their blitzkrieg on May 10 1940.

Failed actions

In the tumultuous few weeks which followed that onslaught, the battalion was part of the 51st Highland Division, which had become separated from the rest of the BEF and was under French command.

After a series of failed actions to halt the advance of the Germans, who had vastly superior firepower and troop numbers, the Division fell back towards the coast and were expecting to be evacuated through the port of Le Havre.

But, when the Germans cut the road, they fell back to St Valery-en-Caux where a defensive perimeter was created until they could be rescued by the navy.

The evacuation was set for the night of June 11. But it never happened.

Instead, thick fog and heavy rain prevented the navy coming in to St Valery and, after the Germans captured the cliffs overlooking the harbour, no ships could approach the shore without facing a direct assault from heavily-armed enemy forces.

The situation was now impossible and the Division was forced to surrender.

In common with almost 2,000 of his colleagues in the 1st and 5th Battalion Gordon Highlanders, Mr Straughan became a prisoner of war.

But not for long.

Instead, it was merely the start of a remarkable series of incidents in his life which have been chronicled by Stewart Mitchell, a volunteer historian at the Gordon Highlanders Museum in Aberdeen, who has written a book about the men of St Valery.

He said: “In Malcolm’s case, his position was attacked and after the men’s ammunition was exhausted, they were surrounded by tanks and motor cyclists bearing machine guns who took them prisoner.

“Following the surrender, the Germans force-marched their prisoners through northern France, Belgium and into Holland where they were bound for five years of captivity in Germany and Poland.

“However, on June 23, during this march through northern France, Malcolm Straughan slipped, unseen, out of the stream of marching men, near Doullens, and hid until the column had passed by.

“Travelling in the hours of darkness, he navigated by the stars to the coast where he thought he might find a boat that would take him back to Britain.

“This proved fruitless, so he travelled on foot further south where he was assisted by local people who put him touch with the French Resistance and he met up with two other escapees, Neil Rae and Bill Burnett, both 1st Battalion Gordon Highlanders.

“On September 22 1940, they were being couriered into the unoccupied (Vichy) zone of France by a French woman and boarded a train travelling south.

“At Chateauroux, their papers were checked and, because they had not been stamped by the Nazi authorities in Paris, they were refused permission to continue.

“Together with some civilians, they were locked in a waiting room. But, once more, they escaped from this and went to the goods yard where they bribed some French railwaymen to smuggle them onto a goods train, eventually arriving at Marseilles where they were arrested by the French police and interned.”

Extraordinary resistance

Mr Straughan had experienced one setback after another.

But this fearless young fellow refused to accept the situation and his extraordinary resilience paid dividends.

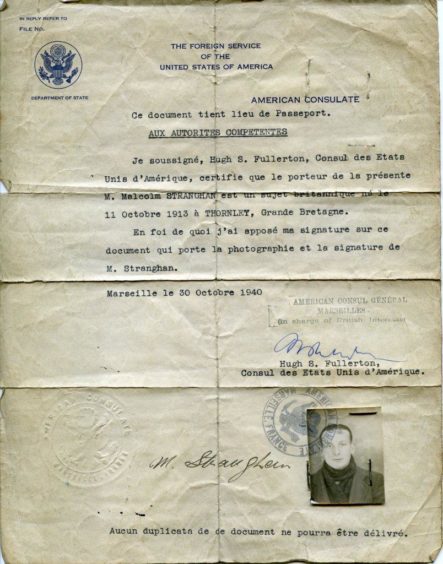

As Mr Mitchell said: “In the spring of 1941, Malcolm escaped and with the help of the Reverend Donald Caskie, a Church of Scotland minister who was operating the Seaman’s Mission in Marseilles, which was the cover for a clandestine operation to assist escaping British soldiers, he obtained papers from the American Consulate.

“This allowed him to prove his identity.

“Then, with the help of the French Resistance, he was guided over the Pyrenees Mountains to Banyuls in Spain, where he was promptly arrested by the Spanish police.

“Fortunately, he came to the notice of the British Embassy and was liberated and taken, via Barcelona and Madrid, to Gibraltar, where he arrived on January 5 1941. From Gibraltar, he was taken by the Royal Navy back to Britain where, after a debriefing, he eventually rejoined the regiment.”

Although the 51st (Highland) Division had been captured at St Valery-en-Caux, it was reformed later that year and fought with distinction in North Africa and Sicily before returning to the UK to re-equip and retrain in the build-up to the invasion of France.

And, would you believe it, Mr Straughan had rejoined the 1st Battalion and was among the troops who landed in Normandy with them on D Day – June 6 1944.

It was a remarkable journey for a man of infinite tenacity and resolve.

Hollywood movie script

But there was still more to recount in a story which might have been rejected by Hollywood as being too unbelievable.

Mr Mitchell said: “On August 26 1944, General Bernard Montgomery’s orders included the sentence: ‘All Scotland will be grateful if the Commander of the Canadian Army, can arrange that the Highland Division should capture St Valery’ (the sector in which the Canadian Army was operating).

“The 1st and 5th/7th Gordons lost no time in setting off and arrived at Veules-les-Roses and St Valery on September 2 and the historic liberation took place, redressing the defeat of the old 51st (Highland) Division four years earlier.

“Malcolm was among the men who returned to the village that day and visited the war cemetery to pay his respects to his fallen comrades.

“But his story does not end there. With the 1st Battalion, he fought on through France and Holland into Germany.

“During the fierce fighting in Holland in February 1945, when the 51st (Highland) Division was engaged in Operation Veritable, Malcolm, acting as the Company Sergeant Major, displayed great valour.

“His Company was at Heyen on February 13 when it was heavily counter-attacked by German infantry, who were supported by two self-propelled guns.

“The Germans had some initial success, infiltrating the British position. But Malcolm saw 10 Germans behind his position and, with total disregard for his own safety, grabbed a Bren gun, rushed into the open and engaged them, killing a number of them and forcing the remainder to flee.

“This single action rallied the rest of his men and the counter-attack was halted.

“Later however, the Germans renewed their attack and as ammunition was running critically low, Malcolm went round the Company positions to resupply the men with reserve ammunition, which necessitated him darting across open ground, again with little regard for his own safety.

“He was immediately awarded a Military Medal to mark his bravery that day.”

By the time the war finally ended, Mr Straughan had been involved in some of the worst and best moments of the conflict, had witnessed the death of pals, survived numerous brushes with the German authorities and risked his life to save others.

But he never forgot the assistance which he received from Rev Caskie, the “Tartan Pimpernel” whose own exploits have become famous throughout Europe.

Mr Straughan, a welder by trade, died in County Durham in 1968, aged just 55.

But he had packed more adventure and acts of gallantry into his life than almost anybody else of his generation.

And his redemption at St Valery was also a reminder of the immense sacrifice which was made by the 51st Highland Division itself.