From lush art deco pleasure palaces to scruffy fleapits; publicity-grabbing parades along Union Street to seedy blue movie houses with scuttling, incognito punters; the rich history of Aberdeen’s cinemas is a tale worthy of a CinemaScope epic.

Yet 20 years ago, cinema in the heart of the Granite City was to briefly fade to black. In July 2000 it was decided to axe the Odeon in Justice Mill Lane, then the last cinema in the city centre. Film fans faced a trek to the UGC at the beach.

Others were, of course, waiting in the wings. When the decision to close the Odeon was made, the Lighthouse, later Vue, was being built on Shiprow. Work was also ongoing to restore the Belmont for use as a cinema. The UGC at Queen’s Links became Cineworld and was later joined by its sister cinema in Union Square.

I grew up in a very rough

area and going to the pictures

was something we used to do.”

But the Odeon, opened in 1940, was the last of the old style picture houses that had been so integral to the life of Aberdeen for more than 100 years – a city once famed for having more cinemas and cinema seats than any other in the UK.

It’s a story which has long fascinated the city’s Lord Provost Barney Crockett – a keen local historian, who has given a talk on the subject more than 200 times.

“Every time I give it, Aberdonians tell me something else about the cinemas,” he said. “I grew up in a very rough area and going to the pictures was something we used to do.”

Cinema had its beginnings in March 1895 in Paris with the first screening of moving pictures to a paying audience.

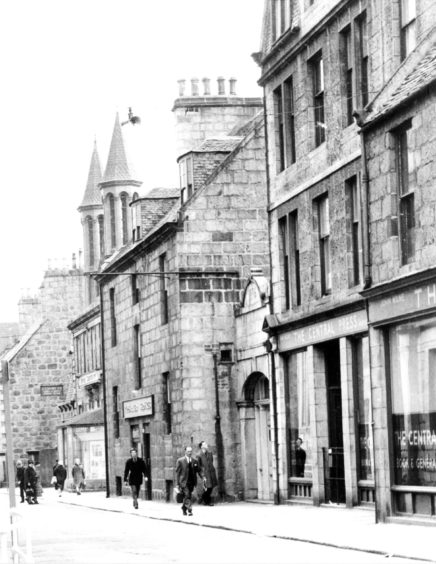

Aberdeen wasn’t slow in catching up with the flicks with the Music Hall screening a series of short films in September 1896, giving it bragging rights as the city’s first cinema.

“Cinema in Aberdeen goes amazingly far back,” said Mr Crockett. “And we still have two cinemas today that were operating as cinema sites way back. The Belmont was showing films in the 1900s and where the Vue stands today there has been a cinema since that time, too.”

The 1910s saw an explosion of filmhouses, for an unexpected reason, said Mr Crockett.

“Originally, cinemas would mainly have been to entertain very poor children in the east end of Aberdeen, that’s where they would make a lot of money,” said Mr Crockett.

“So we had a number of very rough cinemas in the east end aimed at poor kids. In 1918, the council brought out a rule that cinemas couldn’t open later than 10 o’clock at night. In other words, they had been opening later for mainly children. I’ve calculated there would have been about 1,500 unaccompanied little children on the streets of Aberdeen at 10 o’clock at night when the cinemas closed.”

This almost Wild West approach to cinema created some notoriously rowdy cinemas, like the Casino on Wales Street, where the balcony didn’t even have a barrier, said Mr Crockett.

The era also gave rise to some quirks in keeping the young ones in their seats and entertained.

Mr Crockett said: “There was a cinema called the Star, which was just an old church hall. A young husband and wife took it over in the 1920s called Bert and Nelly Gates. They went on a one-week course on how to run a cinema.

“They would entertain the kids by acting out the story in front of them and giving it voice.”

They also pulled in others to speak aloud the lines of the silent films – including one of Aberdeen’s most memorable characters, Cocky Hunter, famed for his Castlehill emporium.

“He used to be able to do a posh accent, allegedly,” said Mr Crockett. It was boasting of his talents that earned Cocky his nickname.

Part of the drive of early cinemas was tied up with the temperance movement, steering kids away from the demon drink, which meant many screens were owned by lemonade companies, such as Hayes and Sangs. But that didn’t guarantee good behaviour.

“There was a thing called the penny rush. You would pay a penny to get in, but people would all rush in and folk would try and cheat,” said Mr Crockett. “The owner of the Belmont had an innovation, where he would try to make people wait to pay their penny by giving them a tangerine as well.

“Of course, kids being kids they just threw them about, so eventually you got your tangerine on the way out. The behaviour back before the First World War was much worse than anything you would get today.”

The Globe was famous for

its fleas. The saying was

you would go in with a jersey

and come out with a jumper.”

This era saw the arrival of cinemas like the Star Picture Palace on Park Street and the Globe – or Globie – now a lighting showroom at the Mounthooly Roundabout.

Mr Crockett said: “The Globe was famous for its fleas. The saying was you would go in with a jersey and come out with a jumper.”

But the 1920s saw a shift from keeping the kids entertained towards films aimed at women – a push pioneered for moral reasons.

“The birth control movement showed films to huge audiences of poor women, mainly at the Casino. It was all melodramas to show why you shouldn’t become pregnant.”

That tone shifted as the 20s progressed, particularly with the films of Rudolph Valentino, with films such as The Sheik guaranteed to have his fans swooning in the aisles.

There were enough seats that

everybody could go to the cinema

one a half times a week and there

would still be enough room.”

The true golden era of cinema in Aberdeen was ushered in at the end of the 1930s, with 1939 cited as the peak year for cinema attendance around the world.

Mr Crockett said: “At that time Aberdeen had the biggest number of cinemas per head. In 1939 there were 20 cinemas operating at one time. There were enough seats that everybody could go to the cinema one and a half times a week and there would still be enough room.”

This was the rise of what were known as the “super” cinemas, huge, lush, art deco creations designed to pull in thousands of people across the city, hungry for the next big film.

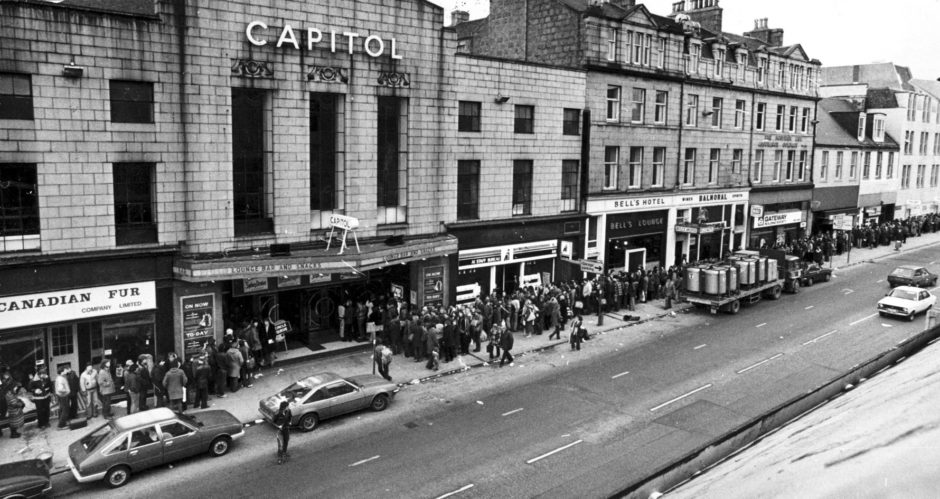

“The first and grandest of them in Aberdeen was the Capitol,” said Mr Crockett. “It was a superlative cinema that opened in the early 30s. Amazingly, it was all made in Aberdeen, the whole building, the furniture, it was all done in Aberdeen.

They were beautiful

cinemas. They were

art deco masterpieces.”

“They voted on which company should make the seats. Each of the local companies like Galloway and Sykes, made what they proposed as the décor and then people voted.

“The Capitol was the first grand one then came others, like the Majestic and the Astoria. They were beautiful cinemas. They were art deco masterpieces.”

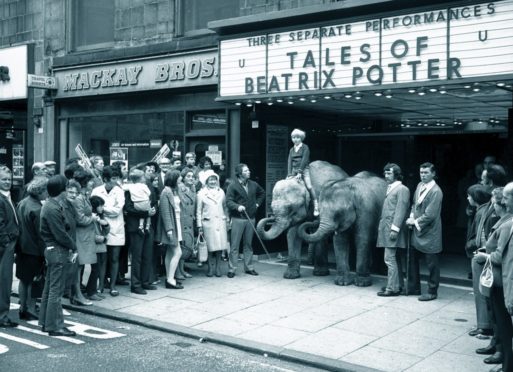

As rival cinemas vied for customers, they would pull off publicity stunts to make them the talk of the town.

“They used to have parades down the Union Street. They could spend money on a huge scale for advertising. For example, you’d have a man dressed up as King Kong on the top of the Odeon.

“When they showed the Bengal Lancers, they hired cavalry men to dress up and go up and down Union Street to advertise it.”

For all that, the supers didn’t fare quite as well as may have been expected. Mr Crockett believes that was down to the loyalty people felt for the cinemas in their own communities.

“While we had these flashy places, nearly all of them got into financial difficulties,” he said.

“People assumed if you gave folk a nice option they would go for that, but they were still going to the rough cinemas. My theory is that they preferred the informality, where they were known and had a relationship.

“For example, the guy who ran the Torry Cinema, on Crombie Road, used to serve ladies’ afternoon tea while they were watching the film, going round with a tray and serve them. He also used to put up a slide in front of the film if you wanted to send a message to somebody. You could say ‘Elsie, your tea’s ready’ and he would put it up in front of the picture. Folk liked that.”

As the Golden Age of Hollywood faded, so did the super cinemas. Television was now in the ascendancy – not to mention the way housing was improving across the city, making homes far more comfortable.

“Cinemas were fighting to keep audiences, so more extravagant films were coming out, using things they couldn’t do on TV, like CinemaScope. The most famous one like that was Ben Hur,” said Mr Crockett.

The 1959 film did, indeed, create a clamour with everyone wanting to watch Charlton Heston in the epic, chariot race and all, especially impressionable kids.

Mr Crockett said: “Someone told me about forcing their mother to give them extra money to see Ben Hur. When they went home a couple of hours later his mother said ‘where have you been? You’ve not been to see Ben Hur, it’s a four hour film’.

“He replied: ‘It came up saying intermission and I thought that was Roman for The End’.”

This was also a time of outrageous publicity stunts by cinemas in a bid to pull in the punters.

“When Psycho was being screened, I think at the Capitol, there was a nurse in a uniform in attendance when you queued up, in case you fainted when you saw the film.”

As cinemas adapted to the new reality, some took a more risqué – some might argue seedy – approach to survival. And so arrived adult cinemas, with one owner, Ernest Bromberg, leading the way.

He had the News Cinema, showing newsreels and aimed at people coming in from the country for shopping. As TV news became commonplace demand dwindled.

“Bromberg opened the Curzon and it was meant to be like Soho, with risqué films,” said Mr Crockett. “It opened with a great classic Around The World With Nothing On. I used to say that in 1950s Aberdeen it would not have been terrible. I gave a talk at the Buchan Society and this gentleman came past me as I was having me tea and said: ‘I was there, it was pornographic’.”

It was a good excuse for

folk going there to say they

were just interested in the art.”

The Curzon, on Diamond Street, was sold on to become the Cosmo 2, which carried on alternating blue films with Continental art house cinema by the likes of Fellini.

“It was a good excuse for folk going there to say they were just interested in the art,” said Mr Crockett.

Other cinemas followed suit, like the International, then the Grand Central.

At this point in the early 60s, bingo entered the scene and another death knell sounded for the city’s cinemas, with many falling silent save for those who converted to the shouts of “house”.

Tens of thousands of people joined bingo clubs in the first few months of them opening.

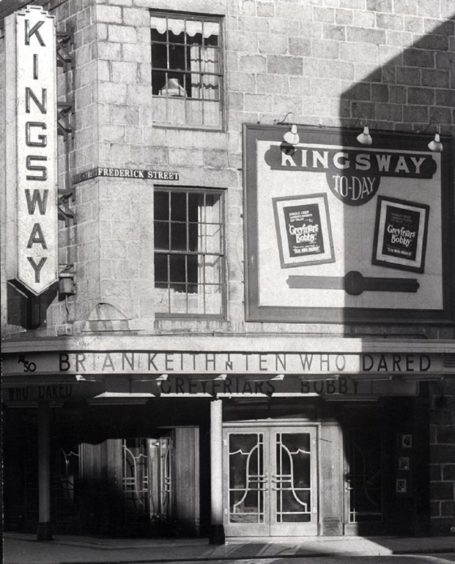

One such was the Kingsway on King Street, still a bingo hall today, but before that a cinema aimed at attracting in the hordes of tourists coming away from the beach.

After that, more TV channels arrived, video film stores exploded and the city’s cinemas went into a steady decline until that fateful day 20 years ago and the Odeon’s final The End.

For many at the time, the closure of the Odeon was seen as another nail in the coffin for cinemas in Aberdeen.

History has proved them wrong, with the two Cineworlds, Vue and the Belmont Picture House all proving to be hugely popular over the years as sound and vision technology, comfort and the whole cinema-going experience has improved.

“Attendances are now, prior to coronavirus, what they would have been many years ago, although it is fewer cinemas with more screens,” said Mr Crockett.

Of course, just how picture houses will work in a post-Covid world remains to be seen.

But film fans, like Mr Crockett, believe it won’t be long until it’s lights, camera, action for the next reel in the story Aberdeen’s cinemas.