There has never been any shortage of pioneering spirit and entrepreneurial flair in Scotland’s DNA.

Just think of all the many inventions which have been associated with Scots from Alexander Graham Bell and the telephone to John Logie Baird and television.

So perhaps, we shouldn’t be unduly surprised at the similar advances which have been made in medical science by a number of trailblazers, who were the catalysts for such significant developments as insulin, the iron lung and the MRI machine.

And, in case anybody is wondering what links that particular trio, the answer lies in their close connection to Aberdeen scientists and doctors, John MacLeod, Robert Henderson and John Mallard, who have all advanced human knowledge.

Indeed, a north-east group is currently planning a series of events to commemorate the discovery of insulin 100 years ago by a trio of scientists.

Among the latter’s number was Mr MacLeod, who studied at Aberdeen University before going on to win the Nobel Prize.

And the MacLeod Centenary Group has been established to support the charity JDRF in its mission to find a cure for type 1 diabetes.

It comprises a broad range of people across many organisations, including Aberdeen University and Aberdeen FC, who have pledged to mark the centenary by raising the profile of JDRF, awareness of type 1 diabetes and the significance of insulin.

Carol Kennedy, regional fundraiser for the organisation, said: “We want to ensure that as many people as possible realise the vital contribution which John MacLeod made in helping so many people with diabetes through his pioneering work with insulin.

“It is a chronic condition, one which has a lifelong impact on those affected by it and their families. We want to spread the word and do all we can to search for solutions.

“We will be holding a series of meetings throughout the year leading up to when JDRF will be marking the anniversary in 2021.”

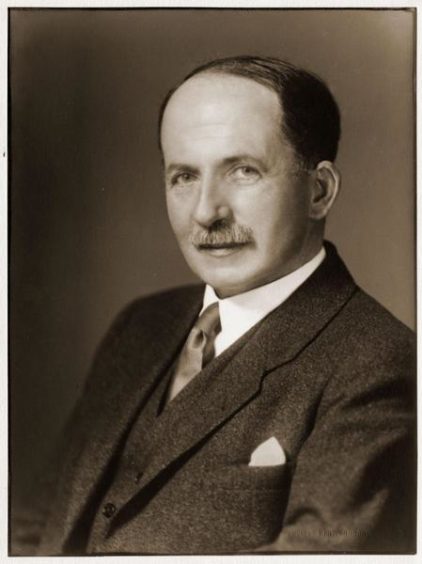

Mr MacLeod was born in Dunkeld in Perthshire in 1876, but soon after his birth, his clergyman father, Robert, was transferred to Aberdeen and the family relocated.

He attended Aberdeen Grammar School and, after being recognised as an intellectually gifted youngster, entered Marischal College at Aberdeen University to study medicine.

He moved to Canada upon graduating and became director of physiology at Toronto University, where he became interested in research on patients with diabetes.

Insulin was developed during his time there in 1921, after he had engaged in groundbreaking work with students Frederick Banting and Charles Best.

Following their collaboration, Mr MacLeod received a Nobel Prize along with Banting, although he and the latter subsequently fell out spectacularly over their rival claims of who had contributed most to the discovery.

It was an unedifying climax to the partnership between these gifted scientists and cast a cloud over their lives, yet it didn’t diminish the scale of their joint achievement.

Mr MacLeod was rather deflated by the saga, but it couldn’t detract from his lofty reputation and he eventually returned to Scotland in 1928 to assume the prestigious position of Regius Professor of Physiology at Aberdeen University.

That was merely the prelude to him becoming Dean of the University of Aberdeen Medical Faculty.

He died in 1935 and is buried in his home city. There is also a plaque near his old house which recognises his contribution to saving and helping countless lives.

Iron lung was created behind closed doors

Robert Henderson was another north-east stalwart who ploughed an idiosyncratic furrow, but it reaped a rich dividend for many of his patients and future generations.

While working as an apprentice in a local Aberdeenshire garage, he was encouraged by one of his teachers to pursue a career in medicine.

The youngster duly embarked on a distinguished academic life, but even while he was studying, it emerged he had been drawing up an idea which required some basic hardware from a ship’s chandler.

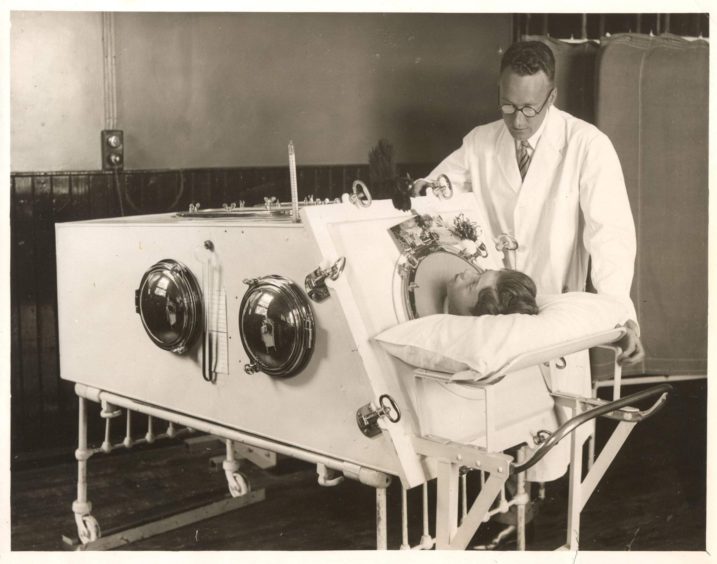

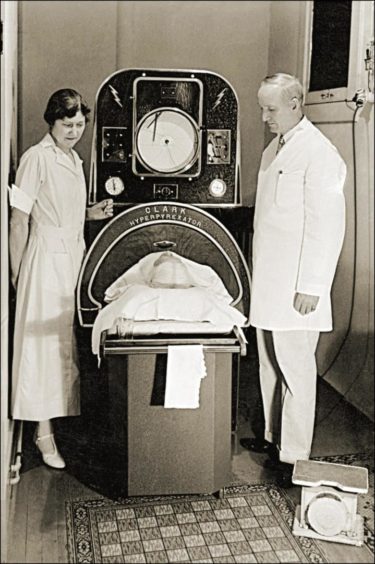

His unique contraption was put together in the evenings and at weekends with the help of Aberdeen City Hospital’s engineers, and was mounted in a cabinet on the base of a children’s cot and quickly became known as the Henderson Respirator.

It was the first iron lung and soon demonstrated its worth.

Because, just four weeks after its construction, it was deployed to save the life of a 10-year-old boy, farmer’s son Charles Forbes from Whitehill of New Deer in Aberdeenshire, who was suffering from infantile paralysis, now known as polio.

Despite being a ground-breaking development, the local medical officer of health condemned the ensuing publicity and, in what now seems an absurdly petty decision, Mr Henderson was disciplined for using hospital facilities to build the machine.

As a consequence, his draft document on the case was never submitted for publication.

But this oversight was eventually corrected in 1997 by a paper in the Scottish Medical Journal, leaving just the small matter of 63 years between draft and publication.

Mr Henderson, who had graduated from Aberdeen University in 1929 and became resident medical officer at the City Hospital, moved to London in 1935 and plied his trade in myriad different vocations before his death in 2000, aged 98.

But there was a touching coda to his early exploits in the Granite City, as recounted by the renowned journalist, Jack Webster, who died earlier this year.

The latter recalled: “That first iron-lung patient, Charles Forbes, really enjoyed his bonus years of life, but when he passed away in the 1950s, his brother Ian spotted a stranger among the mourners.

”It was none other than Robert Henderson, who had come up from London specially to be at the funeral service.”

MRI technology was developed in Aberdeen

He was the pioneering medical physicist whose Aberdeen University team made a global breakthrough by creating the MRI scanner.

Professor John Mallard, who has died at 94, played a crucial role in the development of two of the world’s most important technologies – magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and nuclear medicine imaging which includes positron emission tomography (PET).

Under his leadership, the Aberdeen University group built the first whole-body MRI scanner which the city’s clinicians were then able to use to carry out the world’s first-ever body scan of a patient from Fraserburgh.

MRI machines are now used all over the world in the diagnosis and treatment of cancer, dementia, and a wide range of other conditions and injuries.

Prof Mallard was also a champion of PET imaging, even though the technology was still very much in its infancy at the time.

After retiring from the university in 1992, he was awarded an OBE in the Queen’s Birthday Honours List the same year and was awarded the Freedom of the City of Aberdeen in 2004 for his pioneering work in medical imaging.

Professor Siladitya Bhattacharya, head of the university’s school of medicine, medical sciences and nutrition, said: “We are deeply saddened to learn of the passing of Prof John Mallard who, along with his team helped change the face of medical imaging.

“His legacy lives on through the technology that saves lives on a daily basis and we are proud that he carried out such ground-breaking work at Aberdeen University.”

Emeritus Professor Peter Sharp, added: “John Mallard played a major role in the development of Medical Physics, both here in the UK and abroad.

“Appointed as the first holder of the chair in Medical Physics in Aberdeen – which was also the first such chair in Scotland – his tenacity and ‘can do’ approach led to a remarkable series of developments in medical imaging, culminating in his group building the first whole body clinical MRI machine.

“It is no understatement to say that hundreds of thousands of patients worldwide have benefited from his vision for medical imaging.”