It was a case which provoked controversy, a wrongful verdict and a death sentence, which was later commuted, though not before an innocent man had served nearly 20 years behind bars.

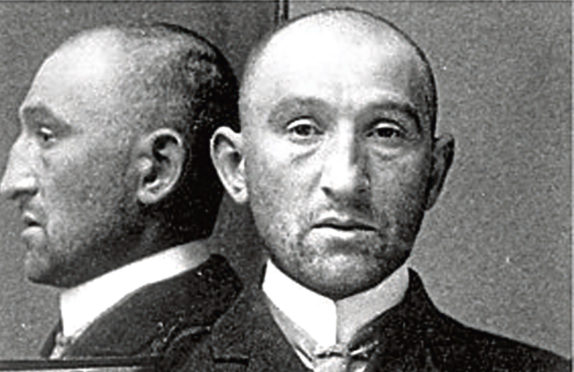

And even now, more than a century after Oscar Joseph Slater found himself in the dock on the charge of murdering Glasgow woman Marion Gilchrist, the case remains Scotland’s worst-ever miscarriage of justice.

The man, who was born Oskar Josef Leschziner in Germany to a Jewish family in 1872, was depicted in the newspapers of the time as a nefarious character, a disreputable individual who was prepared to steal from and bludgeon to death a 83-year-old wealthy heiress.

The police were not initially interested in looking for anybody else and their pursuit of Slater almost cost him his life. Then, despite being spared that outcome, he was forced to serve almost two decades of hard labour at HM Peterhead Prison.

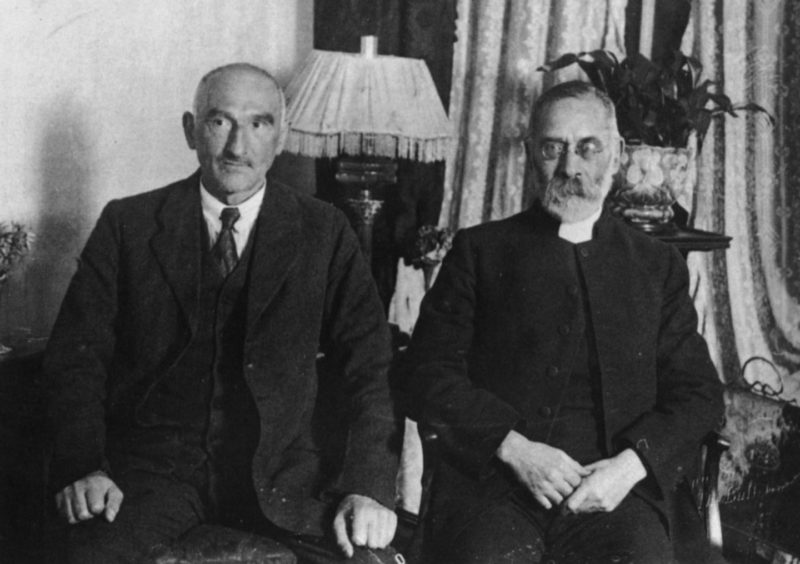

His plight was highlighted by multiple journalists, a succession of lawyers and the growing campaign to have his conviction overturned was subsequently taken up by the Sherlock Holmes creator, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

Yet this was no Baker Street three-pipe problem with a speedy solution. Quite the contrary. And Doyle was not alone in believing Slater was judged on his character, not his deeds.

He had arrived in London in 1893, aged 21, where he worked as a bookmaker, using several different pseudonyms, including “Anderson”, which later cost him dearly.

He was no angel and was prosecuted for alleged malicious wounding in 1896 and assault the following year, although he was acquitted in both instances.

But after moving to Scotland, and earning the reputation as a well-dressed dandy, professional gambler and dealer in precious stones, there was a dramatic downturn in his fortunes when Miss Gilchrist was beaten to death during a robbery at West Princes Street in December 1908, while her maid Helen Lambie had popped out of the house for a short period.

Although the victim had an expensive collection of jewellery in her possession, the only piece stolen was a brooch. And the investigators soon began to assemble a detailed, revealing and – as Doyle later pointed out – “wholly erroneous“ case against Slater.

They learned that, shortly before the murder, a caller to Miss Gilchrist’s home had been “looking for somebody called Anderson”. They smelled a rat when Slater left for New York five days after the incident. And they almost jumped for joy when it emerged he had been spotted trying to sell a pawn ticket for a brooch.

The police soon realised the ticket was for an entirely different item, but regardless of this setback, applied for Slater’s extradition. When he discovered they were wanting to question him, he voluntarily returned to Scotland with the aim of clearing his name.

But this was just the start of his long descent into a Kafkaesque nightmare.

The trial, which elicited feverish attention in the press and stirred up widespread public interest, was presided over by Lord Charles John Guthrie, whose controversial summing-up is now widely regarded as being highly prejudicial.

Defence witnesses had provided Slater with an alibi, while it was confirmed that he had planned and announced his trip to America long before Miss Gilchrist’s murder.

However, none of this mattered to the jury, who convicted him by a 9-6 majority, with five of the half-dozen reaching a “not proven” verdict.

In May 1909, he was sentenced to death, with the execution scheduled for later that month. But there was an outcry at that decision and his lawyers organised a petition which rapidly gained more than 20,000 signatures: a development which materialised almost a century before the arrival of social media.

Eventually, the Secretary of State for Scotland, Lord Pentland, issued a conditional pardon and the sentence was reduced to life imprisonment.

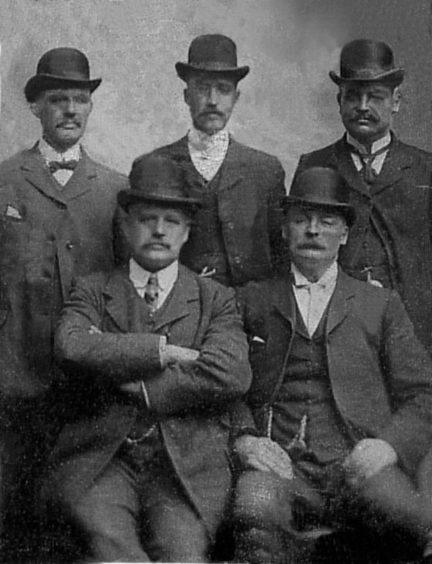

This later sparked a dissection of the whole Scottish legal system and highlighted the many flaws in the prosecution argument, including the fashion in which Slater was conspicuously contrasted with nine off-duty policemen during a rigged identification parade.

As early as 1910, Scottish lawyer and criminologist William Roughead published The Trial of Oscar Slater, which demolished much of the evidence against the convicted man.

Then, in 1912, Conan Doyle, who had examined the proceedings and concluded that the affair had been “reprehensibly” handled, released The Case of Oscar Slater, a passionate plea for a full pardon which resonated among Sherlockians, but failed to sway the authorities.

In 1914, a detective in the case, John Thomson Trench, provided information which had allegedly been deliberately withheld from the jurors by the police. But he was dismissed from the force and prosecuted on trumped-up charges from which he was eventually acquitted.

Meanwhile, even as the clock ticked and the Great War came and went, along with a General Strike in 1926, the hapless Slater remained incarcerated in the north east of Scotland.

The prison itself closed in 2013, but Alex Geddes is the operations manager at the popular Peterhead Prison Museum in the Blue Toon and has methodically studied the Slater story.

He said: “It was a murky episode throughout by the Glasgow police and others who were in authority at the time.

“Oscar Slater’s sentence was changed to ‘penal servitude’ and that is why he was sent to Peterhead which was the only true convict prison in Scotland.

“Prior to Peterhead opening [in 1888], if you were sentenced to penal servitude in Scotland, you would have been sent to England to work or have been shipped off to Australia.

“Oscar pleaded his innocence from the outset and he managed to get a message out to Conan Doyle via another inmate who was released and who slipped the note under his denture plate – the only part of his body which was not searched before his release.

“The maid who initially claimed to have seen Slater leave the flat never appeared at the retrial – no doubt ashamed of the lies she had told.

“Some people thought [the murderer] was the nephew of the heiress, and the family was so wealthy and had connections with the police and the law that they managed to ‘fit up’ Slater, but this was never proved.

“We still have Slater’s cell, which will be opened to the public in 2021 in an exhibit area which is being held back because of the Covid-19 closure, and his story is told on an audio set at the museum. This case still generates a lot of interest.”

Finally, in 1927, The Truth about Oscar Slater by William Park came into the public domain and the contents led to Alexander Munro MacRobert, the Solicitor General for Scotland, reachIng the conclusion it was no longer proven that he was guilty.

But it was not until July 1928 that his conviction was quashed on the grounds that Lord Guthrie had failed to direct the jury properly about the irrelevance of allegations which had been made about Slater’s character.

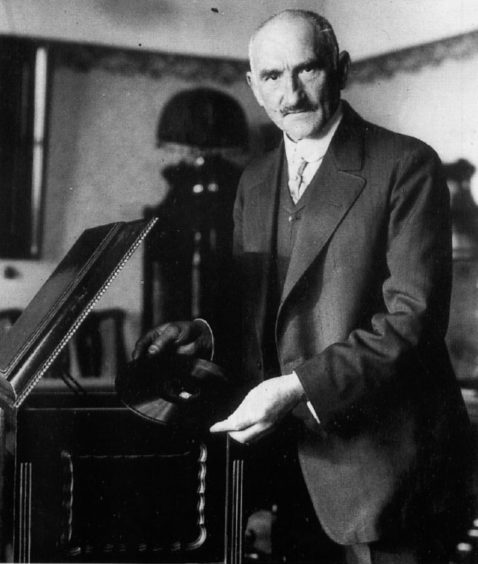

After serving 19 years of hard labour – and doing so with a dignity which might have been beyond other people in his situation – he received only £6,000 compensation.

And that was still not the end of his travails.

In the 1930s, Slater married a Scottish woman of German descent and settled in Ayr, where he repaired and sold antiques.

However, as a couple who were designated as “enemy aliens”, Slater and his wife were interned for a time at the outbreak of the Second World War, even though he had long since lost his German citizenship and had been nowhere near his homeland for more than 40 years.

Most of Slater’s surviving family, including his two sisters, perished as victims of the Holocaust. He himself died in Ayr in January 31 1948 of natural causes, aged 76.

Friends testified to how his youthful brashness and bravado were gradually, inexorably squeezed out of him as his incarceration continued. It was a very different person who left Peterhead Prudin from the one who had walked through the doors.

In Glasgow rhyming slang, “See you Oscar” rhymes Slater with later.

One doubts he would have derived much consolation from learning that his legacy lives on.

While Sir Arthur Conan Doyle didn’t approve of Slater’s lifestyle, he worked tirelessly to clear his name.

His work The Case of Oscar Slater demonstrated, point by point, that the prosecution case was flawed in many ways.

For example, he explained that Slater had travelled under an assumed name because he was with his mistress. He was trying to avoid detection by his [first] wife, not the police.

Conan Doyle concluded that Miss Gilchrist had opened the door to her killer and surmised that he knew the latter. She and Slater had never met.

There were many other issues which he raised, not least in connection with Helen Lambie.

It emerged that before the maid named Slater as the man she had seen in the hallway of Marion Gilchrist’s house on the day of the murder, she had given the police another name.

Almost unbelievably, the officials chose to ignore this information.

Conan Doyle was outraged and declared: “How the verdict could be that there was no fresh cause for reversing the conviction is incomprehensible.

“The whole case will, in my opinion, remain immortal in the classics of crime as the supreme example of official incompetence and obstinacy.”

It was a damning indictment on an infamous chapter in Scottish legal history.