Zig-zagging up to a height of 500ft, Dalmunzie railway was built 100 years ago in wild heathery moorland near Glenshee. Gayle Ritchie finds out more about the “lost” line.

Hidden deep in the wild moorlands near Glenshee, it’s perhaps one of the last places you might expect to find a railway line.

But until 1978, a narrow-gauge line, about two-and-a-half miles long, operated here, and remains of it can still be seen.

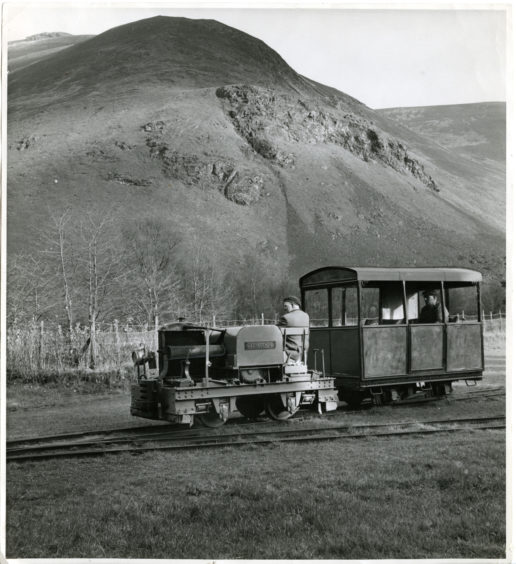

The railway, which zig-zagged up to a height of 500ft, was built 100 years ago – in 1920 – to shuttle shooting parties up the glen to grouse moors and deer forests from Dalmunzie House.

It terminated at Glenlochsie Lodge, a shooting lodge, now ruined, and brought game back to the hotel’s larder.

The journey reputedly took about 25 minutes and the ghillies of the estate were charged with driving the locomotives.

The railway line was owned, funded and financed by Sir Archibald Birkmyre, who had bought the estate in 1920, having leased Dalmunzie (pronounced Dalmungie) as a shooting retreat since 1907.

Keen to enlarge the “humble” house on a massive scale, he used the railway to bring down stone from a quarry in the glens for construction work – as well as to ferry himself and guests up into the hills.

He also built Britain’s highest golf course on the estate, a nine-course gem with scenic mountain vistas.

Sir Archie had made his fortune from his family’s jute manufacturing and merchandising business, with factories all over India.

Their UK operations traded out of Glasgow under name of The Greenock Rope Company.

Sir Archie became a knight bachelor in 1917 and a baronet in 1921 for his vital services of manufacturing sandbags in the First World War.

He was a man on a mission – excited about Dalmunzie’s future and its excellent shooting opportunities.

He was a keen shot, having had plenty of practice in India where hunting expeditions was a thrilling pastime for the wealthy gentry.

Hard graft

The geography of the land at Dalmunzie meant something unique would have to be constructed but Sir Archie was undaunted by the enterprise – he already had experienced narrow gauge railway journeys in India.

Here, railways often took passengers up to the cooler altitudes of hill stations overlooking the Himalayas to escape the burning heat.

Once plans were drawn up, a squad of eight Irish men, a road gang from Braemar, were employed to dig out the trackbed at Dalmunzie.

All the hard graft was done with picks, shovels and crowbars plus a few sticks of gelignite were used to remove or split large rocks blocking the way.

Sir Archie was lucky to source a supply of rails from Aberdeenshire.

Once used as a light railway in France during the First World War, they were returned to stock after hostilities ended and held in a secret location.

It’s thought that Sir Archie managed to acquire the rails “dirt cheap” after speaking to an official in the Ministry of Defence.

The reinforced concrete sleepers which carried the track were all made on the estate by “navvies” during the harsh winter months.

As well as the two petrol-driven engines, the Dalmunzie railway boasted two carriages – a first class one used as an observation car with hide-covered swivel seats and sun blinds, and a second class, less luxurious one with bench seating for stalkers and ghillies. There was also a truck to carry home the game.

Rollercoaster ride

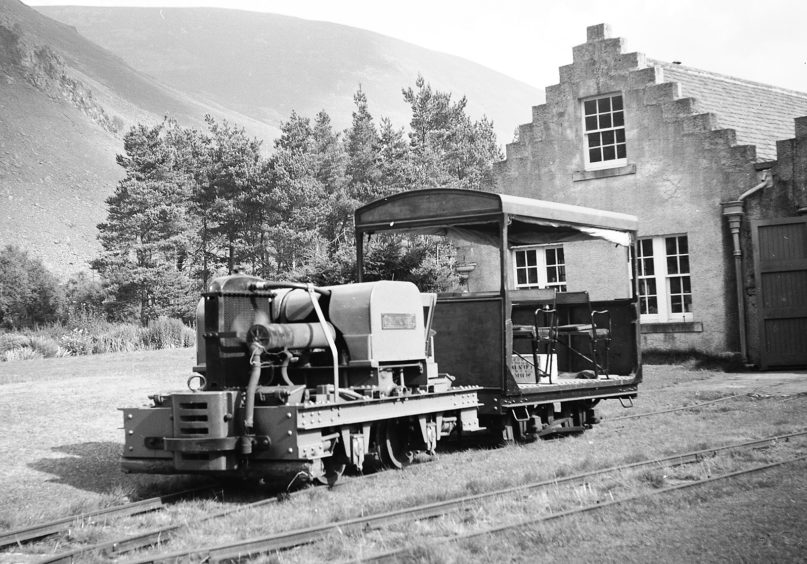

Tales abound of the “rollercoaster ride” the two engines – named Dalmunzie and Glenlochsie – provided on the downhill run!

And a news report in 1929 described the line as “one of the strangest little railways in Scotland”.

In 1978, it closed due to the expense involved in maintaining it, and of course, four-wheel drive vehicles were better equipped to navigate the steep, tricky terrain.

The track was dismantled and the whole lot – the engines, carriages and concrete sleepers – was sold to a museum in Northumberland.

However the trackbed is still there, imprinted in the landscape, and relics of the line can be found in the form of the odd concrete sleeper, old bridges and wooden buffers.

And the hotel kept the name plates of the two locomotives – they’re on display in the bar.

It’s also thought that there was a bell on the side of the house which was rung before train departures.

Back in September 1929, a feature in the Port Glasgow Express reported that only a few scattered residents in the valley were aware of the railway’s existence, while visitors came and went without hearing anything about it.

“Only occasionally when a climber notices puffs of smoke from an adjoining hill and asks questions in the village is the story of the railway ever told,” the report said.

Magnificent location

There had been proposals to extend the line further up into the glen but these were shelved on Sir Archie’s death in June 1935.

In 1988, an engine, two small coaches and some lengths of track were bought and returned to Dalmunzie Estate.

There were plans to re-lay some track and run the engine once again, but this ever came to fruition.

Mount Blair archivist John Manning is among a group of people keen to see the railway reinstated.

“So many railways have been restored by enthusiasts,” he said.

“It’s a pity that the Dalmunzie railway has not, particularly as it is so interesting and in such a magnificent location.”

Stumbling on a “secret railway”

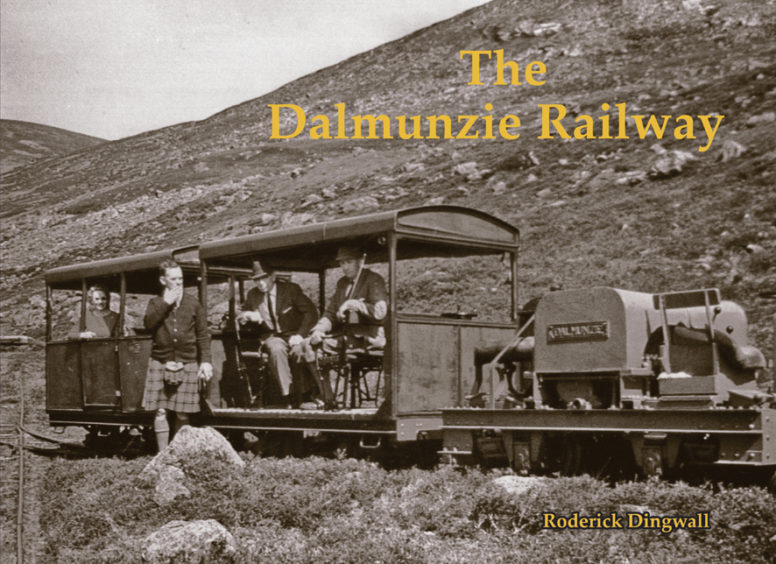

Roderick Dingwall, a major fan of the quirky railway, wrote a book about it in 2017.

Simply titled The Dalmunzie Railway, it’s published by East Ayrshire-based Stenlake Publishing.

In it, he reveals he stumbled on the railway line in September 2001 during a showery attempt to climb Glas Tulaichean, a Munro near Glenshee.

Cold and hungry before he had even set off, he stopped in at Dalmunzie Hotel for a bite to eat.

While enjoying a packet of crisps, he noticed a postcard of the old railway which showed “two vintage carriages, an engine standing amid heather-clad hillsides and a distinguished kilted gentleman standing beside the train…looking apprehensively up the next section of steeply graded track”.

Being a lifelong narrow-gauge railway enthusiast, Roderick wondered why he’d never heard of the railway before.

“Why hadn’t it appeared in any of the hundreds of books in my extensive library of narrow gauge matters?” he wrote.

“Was it a Scottish secret? I was intrigued and had to find out more.”

As he was leaving the hotel, he bumped into the Laird of the estate, Simon Winton, and asked his permission to look around for any traces of remaining railway relics.

Was it a Scottish secret? I was intrigued and had to find out more.”

Roderick was “overwhelmed with ecstasy” as the Laird led him to an outbuilding at the rear of the hotel.

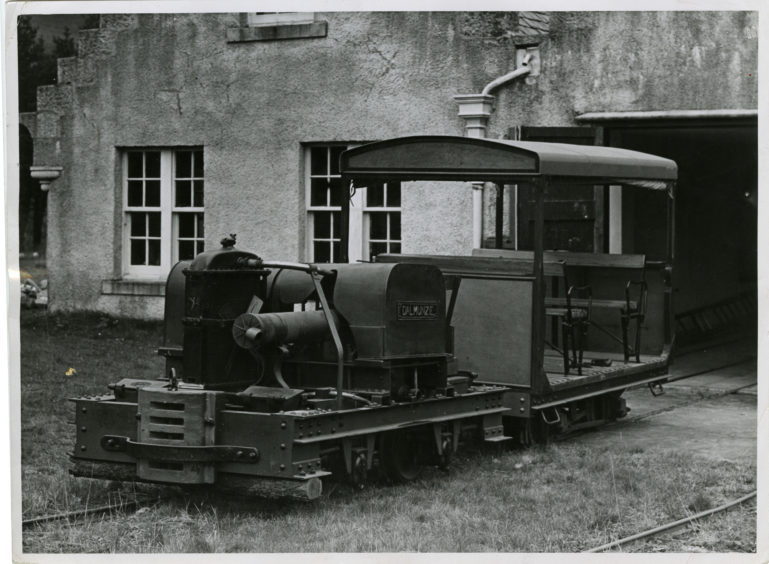

“Here my dreams came true for there sat the Simplex locomotive named Dalmunzie, buried amongst a bevy of bicycles and a labyrinth of lawnmower equipment,” he wrote.

“The two old carriages were hiding there as well, parked huddled together in a cobwebbed corner, covered in a fine layer of dust.

“A baby’s pushchair and an odd assortment of metallic and plastic memorabilia was stacked between the coach seats.

“I was spellbound. It was as though the postcard scene had sprung to life.

“It was magical to realise that the engine and coaches had survived the ravages of time and that they were still in company with each other after many, many years. Age had left its mark but had not deprived them of their dignity.”

Engineering in the wilderness

Setting out to walk along the remains of the old trackbed, Roderick soon came across a stone bridge with sleepers still intact, set between twin masonry plinths.

Finding the track came to a sudden halt at a wooden buffer stop, he picked up the trackbed “about ten feet away, soaring upwards into the sky by the means of a precipitous incline”.

Pressing on, Roderick reached a stone and metal girder bridge which spanned a stream that had carved a deep gorge through the rocky hillside.

“The bridge had rusted handrails to prevent a fall of 15ft or more into the fast flowing waters below,” he wrote. “This was engineering in the wilderness.”

Hidden in the heather at the end of the line, Roderick found a quaint little platform and spotted ruined Glenlochsie Lodge.

At the time of his visit, the lodge still boasted a tiny bit of wavy tiled roof of a greenish blue hue.

“The premises were still lived in…Glenlochsie Lodge was now the luxury abode of Highland sheep,” he mused.

“After reaching a safe spot amongst the rubble, I noticed the grand fireplace.

“It was so big you could roast a whole ox or stag in it and no doubt previous occupiers must have done so at one time.”

Back at the hotel bar, Roderick noticed a locomotive name plate fixed over the tavern doorway.

He wrote: “As I finished my fourth dram I began to dream I had discovered a secret railway that headed straight to heaven, buried on a Scottish mountainside.”

Info

If you fancy walking along the old Dalmunzie railway line, you can park your car outside Dalmunzie Castle Hotel for a daily £5 charge.