Hidden deep within the iconic mountain of Ben Cruachan on the shores of Loch Awe is Cruachan Power Station. A true marvel of engineering, it was opened by The Queen 55 years ago today – on October 15 1965. Gayle Ritchie explores the story of the “hollow mountain”.

At 1,126m, Ben Cruachan is one of Scotland’s most famous mountains, towering high above a range of sharp, jagged peaks stretching between Loch Awe and Loch Etive.

Its 450-year-old granite rock weathered the elements for 450 million years until it was sliced apart and excavated to make way for a power station.

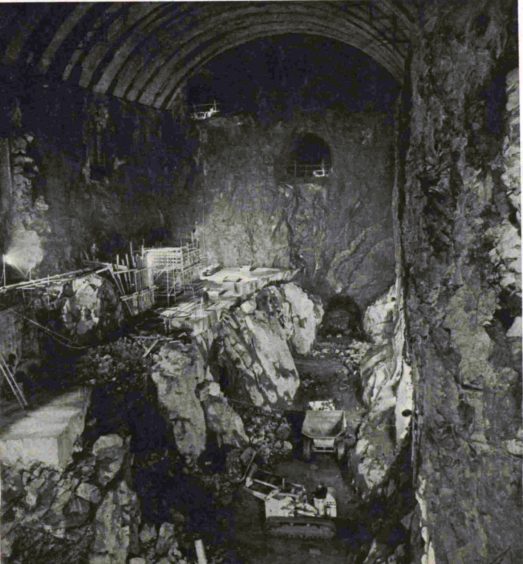

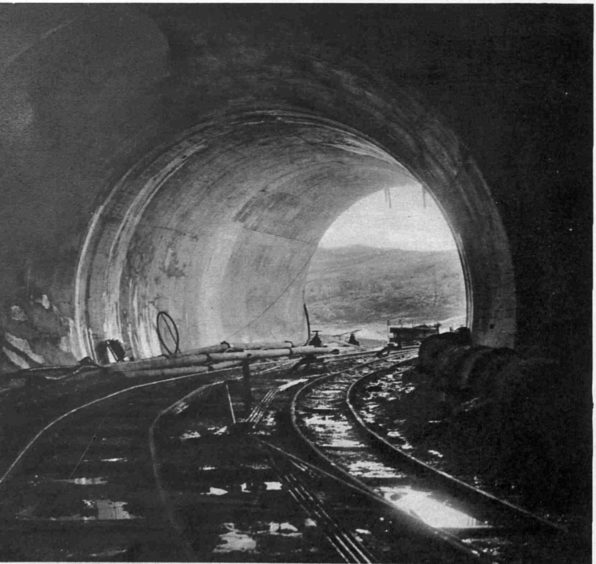

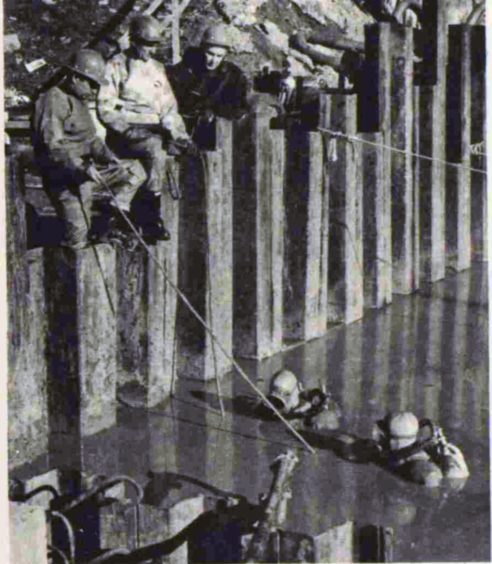

Work to construct the hydroelectricity base started in the summer of 1959 and in 1960, a group of explosives experts, known as “tunnel tigers”, began blasting into the sides of the mountain.

The men used handheld air drills to bore holes in the solid granite rock, which were then packed with gelignite and detonated.

On October 15 1965, Cruachan Power Station – housed inside the hollowed-out mountain – was officially opened by The Queen.

Even Her Majesty, who had arrived on the royal train from Balmoral, was blown away by the sheer magnetism and scale of the place.

As she stepped off the train at nearby Dalmally, a rainbow appeared over Ben Cruachan, as if to order.

A pull of the lever by the Queen and the great machines started turning, generating power for hundreds of thousands of homes.

It was a breath-taking concept – an underground power station carved into the very heart of a mountain – and the first reversible pumped storage hydro system on such a scale to be built in the world.

Twenty miles south of Oban, Cruachan’s massive, man-made cavern sits one kilometre inside the mountain.

At 118ft high and nearly 300ft long, the cavernous machine hall is the size of a football pitch and high enough to house the Tower of London.

Today the cavern is home to four generators powered by water from a reservoir and Loch Awe.

It’s one of only four pumped storage power stations in the UK, providing power for up to 880,000 homes.

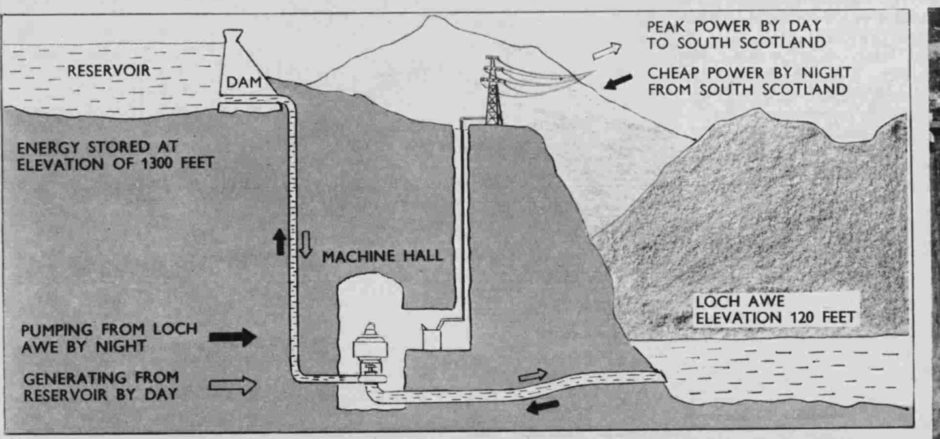

It works like an enormous rechargeable battery, temporarily storing energy by managing water resources between a reservoir in the Argyll hills and Loch Awe, 396m below.

Using its reversible turbines, the station pumps water from Loch Awe to fill the upper reservoir at times when demand for electricity is low.

When demand increases, the stored water can be released through the plant’s turbines to generate power quickly and reliably.

As today marks the 55th anniversary of Cruachan’s opening, the Drax Group, which acquired the power station in 2019, said there is great cause for celebration.

Ian Kinnaird, Drax’s Head of Hydro, said: “When the Queen pulled the lever to send water flowing to Cruachan’s turbines on its opening day 55 years ago, it marked not only the start of the station’s operating story, but the end of many years of construction.

“Cruachan is an engineering marvel carved out of Argyll’s granite bedrock.”

The work to construct the power station was physically demanding and at times, incredibly dangerous.

Tragically, there was a significant human cost for the project with 15 men, many of whom were very young, losing their lives during construction.

Today a carved wooden mural hangs on the wall of the turbine hall to capture and commemorate the myth of the mountain and the men who died – a reminder of the bravery and sacrifice they made.

“We have never forgotten the sacrifice those men made to build Cruachan.” said Ian.

“Last year Drax commissioned a new commemorative tartan with 15 dark blue threads in memory of those who tragically died.”

The tartan, based on the Clan MacColl Sett, which was created in respect of Sir Edward MacColl, the brainchild and pioneer of Cruachan Power Station, has also been used to make special scarves.

We have never forgotten the sacrifice those men made to build Cruachan.”

In terms of its role today, Ian said Cruachan has “never been more important”.

“For 55 years, Cruachan has been providing fast, flexible power for hundreds of thousands of homes across Scotland,” he said.

“Over the last decade, its reversible turbines have been used to pump water to store excess power generated by Scotland’s wind farms, making the station a lynchpin in the country’s renewables revolution.

“The station has never been more important than it is today, and Drax is progressing plans to expand the station so it can play an even greater role in providing flexible power.”

Tunnel Tigers

Nicknamed the “tunnel tigers”, the 4,000-strong workforce drilled, blasted and cleared the rocks from inside the mountain, removing some 220,000 cubic metres of rubble over a six-year period.

The work was physically exhausting – the environment dark and dangerous.

The workers came from a range of background and cultures, attracted to Cruachan’s huge ambition and generous pay.

Polish and Irish labourers worked alongside Scots, as well as displaced Europeans, prisoners of the Second World War and even workers from as far as Asia.

The men would work long shifts – sometimes up to 18 hours – seven days a week.

Some, desperate to boost their incomes, chose to do 36-hour shifts, which they termed “ghosters”.

Those who witnessed Cruachan during construction say the dirt, noise and scale of carving out its innards felt like stepping into “Dante’s inferno”.

One labourer, who started at Cruachan just after his 18th birthday, recalled: “I was in for a shock when I went down there. “The heat, the smoke – you couldn’t see your hands in front of you. It was like stepping into the jaws of hell.”

It was an extremely inhospitable environment to work in. From the water dripping through the porous rocks making floors slippery and exposed electrics vulnerable, to the massive machinery rushing through dense dust and smoke, danger was always present.

Loose rocks as large as cars would often fall from exposed walls and ceilings while the regular blasting gave the impression the entire mountain was shaking.

In total, 20km of tunnels and chambers were excavated, including the kilometre-long entrance tunnel and the 91-metre-long, 36-metre-high machine hall.

Here enormous turbines convert the power of water into electricity, available in homes at the flick of a switch.

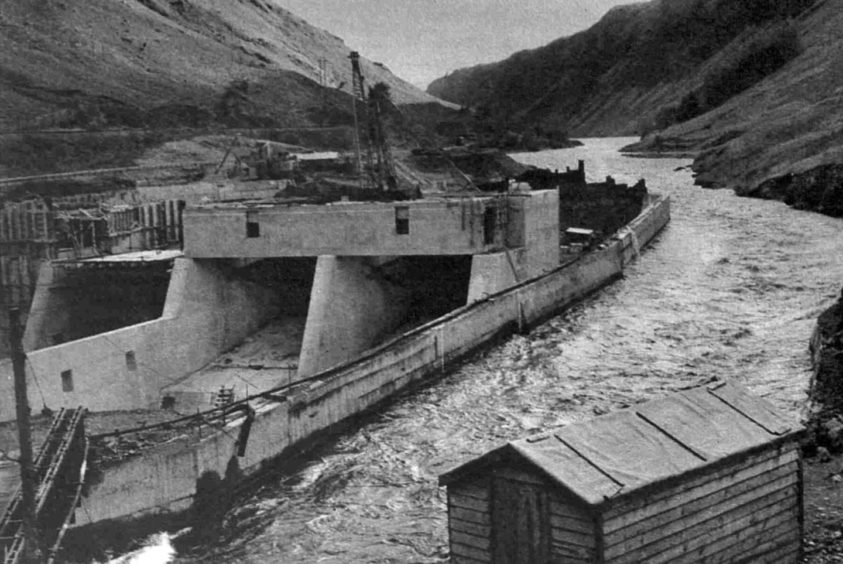

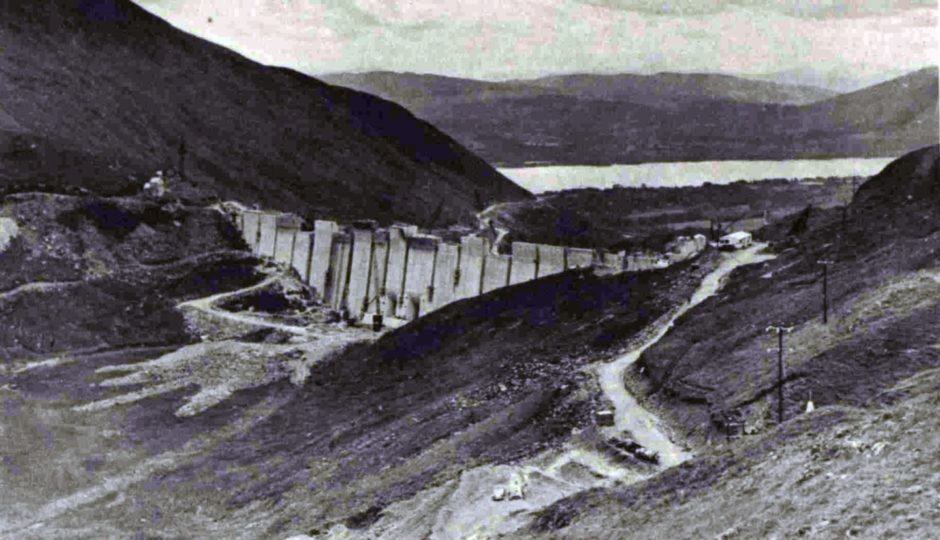

Cruachan Dam

On top of the mountain, another intrepid team tackled a different challenge – building the 316-metre-long dam.

The workers may have escaped the hot, humid conditions at the heart of Cruachan, but their task was no less daunting.

Charlie Campbell, a 19-year-old joiner who worked on the dam, found an innovative way to keep warm.

“You’d put on your socks, and then you’d get women’s tights and you’d put them over the top of the socks, and then you’d put your wellies on and that’d keep your feet a wee bit warmer,” he recalled.

Pouring the concrete of the dam – almost 50 metres high at its tallest point – was precarious work, especially given the challenges of working with materials like concrete and bentonite.

Workers described it as “horrible stuff, like diarrhoea” and when one lad fell into it, it was feared he had drowned. Luckily, he survived the mucky ordeal.

Future

Cruachan’s ability to produce clean and almost instant power has meant that current operators Drax have a wish list to one day dramatically increase its output and even blast again into that ancient rock to create “Cruachan Two”.

They just need to find a way of making it financially viable.