He was a man with an indelible link to the Famous Five, but that’s the only connection between Eddie Turnbull and Enid Blyton.

While the latter’s characters were invariably involved in cartoon crime capers with lashings of ginger pop, the redoubtable customer who became Aberdeen manager in 1965 was more akin to Irn Bru: made in Scotland from girders with an attitude to employing the sort of industrial language which would have made many dockers blush.

Indeed, Turnbull, a thoughtful figure in his dealings with friends and acquaintances, once admitted to being horrified when somebody played him a tape of one of his expletive-strewn rants and it emerged he had used 35 swear words in just a minute.

Here was somebody who really did put the F and C into Football Club.

And yet, the man who starred alongside his Hibs confreres, Gordon Smith, Bobby Johnstone, Lawrie Reilly and Willie Ormond, all of whom have been inducted into the SFA’s Hall of Fame, was the perfect man to lead the Dons forward in 1965.

When he arrived, they were staring at the spectre of relegation.

By the time he left for Easter Road in 1971, he had brought silverware to Pittodrie and transformed the club’s ethos, on and off the pitch.

And that maybe explains why, 10 years after his death, Turnbull remains one of the iconic figures in Aberdeen’s history and heritage.

Eddie told the Dons board: ‘It’s my way or the highway’

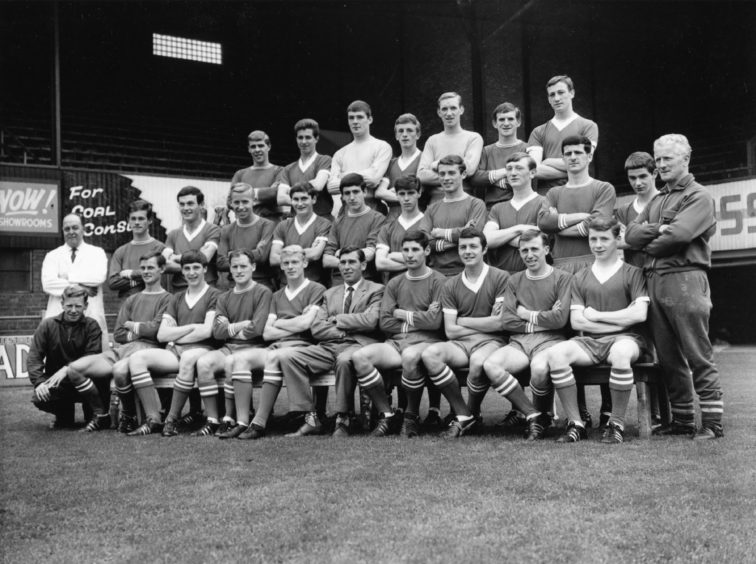

Within months of being recruited to the north-east, Turnbull had dispensed with 17 players, both slashing the wage bill and tackling any dressing-room dissent with a take-no-prisoners approach.

He was equally undaunted about confronting his own board.

As a long-time admirer of Dunfermline inside forward, Harry Melrose, the gaffer went to see chairman Charlie Forbes and told him that he wanted to sign the Pars player.

He was rebuffed in this initial request and told to exist within his means. But Turnbull was nothing if not tenacious and took the decision to demand an emergency board meeting on a Sunday when the committee would usually have been in church or on the golf course. He revealed later that it was a move which “almost ended my Aberdeen career before it had really started”, but this was typical Turnbull hardball.

As he told Forbes about his request, he ended the conversation: “And if you and the board are not there, you can get a new manager.”

A high-risk strategy which summed up the man

His tactics could have blown up in his face, but when Turnbull marched towards the Pittodrie boardroom on the Sabbath, he had a clear message for those in charge.

As he said: “I told them: ‘If you want this ship back on an even keel, you’ll have to realise that it is going to be a huge task. You will have to go along with my plan and that means giving me the money to sign Harry Melrose’.

“I then clearly implied that if I didn’t get the cash, then I would be on my way.

“The sum involved was just £4,000. It was relatively small beer. The directors were clearly taken aback, but since I had enjoyed such a good start with the club and I had the backing of the fans, they knew they could not risk losing me. I got my money and the real business of restructuring Aberdeen was under way.

“I had won one battle, but in a sense, I had won the war, too. For, though we would all have to work like Trojans and it would take longer than I thought, nothing would ever be the same again at Pittodrie. I would make sure of that.”

Turnbull was ‘light years ahead’ of anybody else

The manager wasn’t remotely interested in tolerating players with ideas above their station or fluffy prima donnas who picked and chose their days to shine.

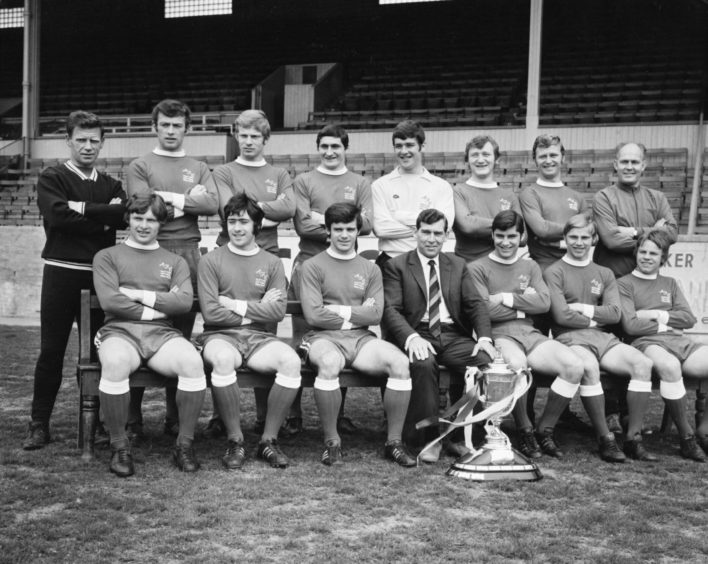

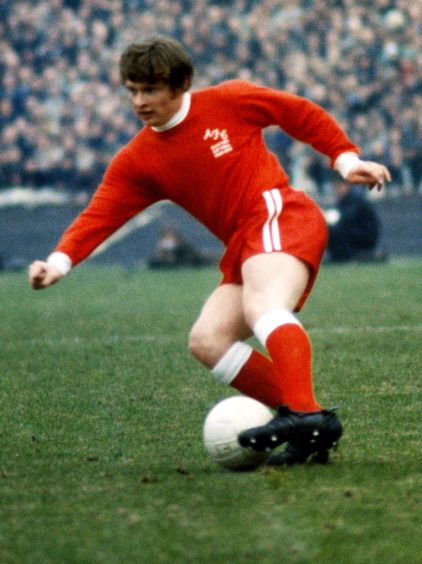

It made him a hard taskmaster, but those who bought into his philosophy included the likes of Martin Buchan, who went on to star for Manchester United and Scotland.

He thought the world of his older mentor and paid an effusive tribute in the foreword of Turnbull’s autobiography Having a Ball.

As Buchan said: “As a football coach, Eddie was light years ahead of anybody else I worked with at club or international level in my career, which spanned 19 years, including the World Cup finals (in Germany and Argentina) of 1974 and 1978.

“After he joined Aberdeen, he embarked upon a youth policy whereby he took young hopefuls, many of them local lads like me, and worked us very hard.

“He gave us the most wonderful education in the game and he made men of us.”

‘I could have gone anywhere after Eddie’s labours’

Buchan added: “He realised, of course, that he needed experienced players to help bring on the youngsters, but even they became better under his guidance.

“When I eventually left Aberdeen to join Man Utd, I felt I could have gone anywhere in the world and played in any system, thanks to the things he taught me about the game.”

It was a measure of the man that, even many years later, his players from his days at Pittodrie and Easter Road still called him ‘Boss’.

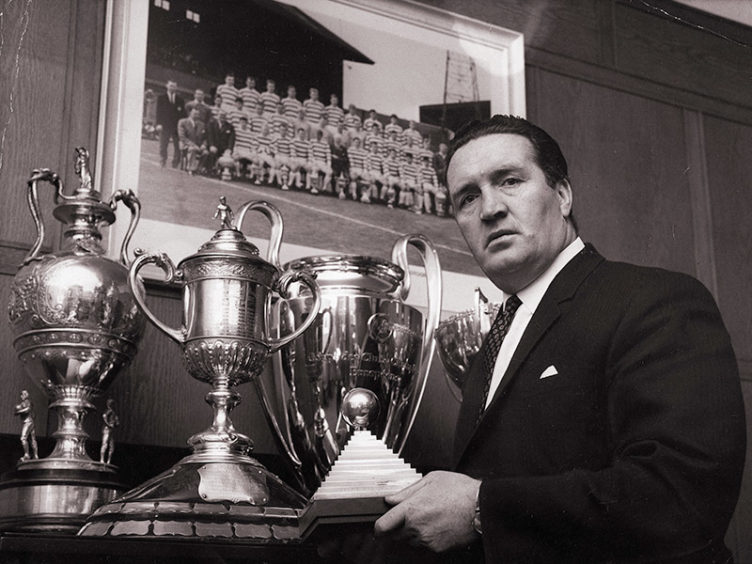

Turnbull’s relentless commitment and dedication became the stuff of legend, but despite his efforts, he had to wait until 1970 to collect a trophy.

But it was one of the sweetest triumphs ever recorded by any Granite City ensemble.

A shot at glory as Dons secured their second Scottish Cup

Football was big business in Scotland in the 1960s and 1970s.

Success against high-class European opponents wasn’t taken for granted, but it happened on a regular basis, including Celtic winning the European Cup and Rangers reaching the European Cup Winners’ Cup in the same year – 1967.

Jock Stein’s players were still at the height of their powers three years later when they tackled Aberdeen in the 1970 Scottish Cup final at Hampden Park.

It was a remarkable occasion, with more than 108,000 supporters at the famous old ground for a contest where the Dons were rated as rank underdogs.

That state of affairs suited Turnbull, whose squad based themselves at the Gleneagles Hotel, where they met a wealthy American who promised them a party if they won (he was as good as his word), and prepared for battle unencumbered by any great expectations.

Celtic featured seven of their Lisbon Lions, including Tommy Gemmell, Bobby Murdoch, Jimmy Johnstone, Davie Hay and Bobby Lennox, and the Glasgow-based media thought this would be another stroll in the park for the Stein machine.

But Turnbull was formidable motivator, an astute tactician, and was blessed with high quality players such as Buchan, Melrose, Bobby Clark, Joe Harper and Davie Robb.

He was also, when required, a scary individual and, prior to the kick-off, recalled: “I gave them an address which would have roused the dead.”

‘I looked calm, but inside I was dancing!’

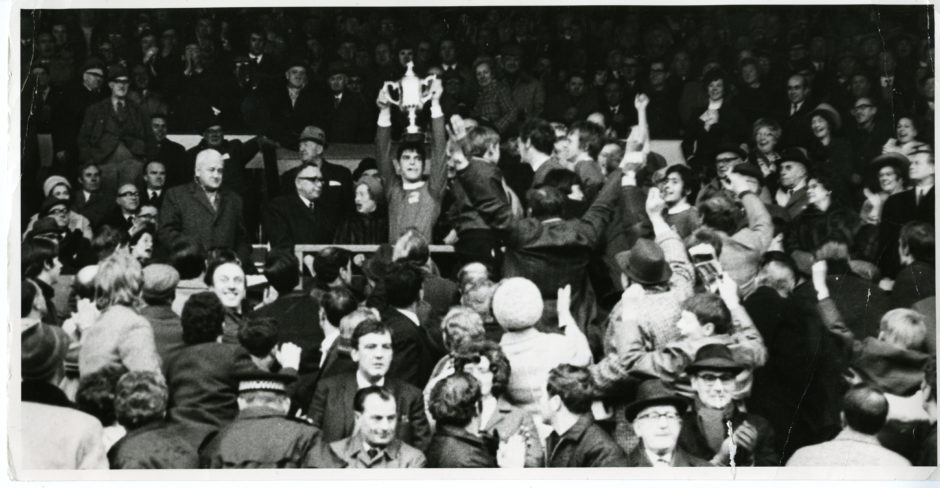

There was plenty of excitement, controversy and coruscating action during the climactic encounter and Aberdeen took the lead in the 27th minute when referee Bobby Davidson awarded them a penalty, which sparked consternation in the Celtic ranks.

Even as the Parkhead men argued their case, Harper, “the coolest man inside Hampden” was spotted by his manager “playing keepie-uppie” with the ball. Then, once order had been restored, he scored after sending Evan Williams the wrong way.

That was all that settled the clubs at the interval, but there was a dramatic end to a match played at a frenetic pace. Derek McKay doubled his side’s advantage with just seven minutes left, yet Lennox narrowed the deficit on the cusp on injury time.

However, as Turnbull recorded: “What followed were the longest seconds of my life until Arthur Graham and Harper combined to give McKay a golden chance, which he converted with glee.

“We had won the cup for only the second time in Aberdeen’s history and we had done the job in style.

“Martin Buchan became the youngest-ever captain (he was only 21) to lift the cup and the lap of honour after the game was wonderful to behold.

“I might have looked calm on the outside, but inside, I was dancing.”

Sweet dreams were made of this for Turnbull and the Dons

The following day, the jubilant Dons collective travelled back to Pittodrie, stopping briefly at Stonehaven to accept the congratulations of the town’s provost.

Then they advanced onto an open-top bus for what even Turnbull described as an “amazing procession through Aberdeen to the Town House”.

“Tens of thousands of people surrounded us all the way through the city and I remember looking at the vast crowds who had turned out,” he said.

“The Lord Provost of Aberdeen was Robert Lennox (the uncle of chart-topping Eurythmics star Annie) and he greeted us and we made our way onto the balcony.

“It was April 12 1970 and it was my 47th birthday, as the Lord Provost announced.

“To have 100,000 people singing ‘Happy Birthday’ to you is really something special.”

A final word about one of Scottish football’s great figures

Turnbull and his team almost added to their reputation with the Scottish championship title the following season, but were eventually pipped at the post by Celtic.

Yet, although he subsequently departed for Hibs, he had been the catalyst for changing attitudes and recruiting players who would enjoy future success with the Dons.

Even in his late 80s, whenever he returned to Pittodrie, he was treated as one of the club’s genuinely groundbreaking individuals who commanded respect.

Jock Gardiner, a member of the AFC Heritage Trust, said: “My only personal encounter with Eddie was in the boardroom at Pittodrie for a midweek match against Hibs not long before he passed away in 2011.

“It was an honour to meet the great man, who despite being elderly was still very sharp.

“We had a good chat and I enjoyed letting him know that my father – a Hibs fan from Edinburgh – had enjoyed watching him as a player in his heyday.”

Having a Ball by Eddie Turnbull was published by Mainstream.