It’s a discovery which has saved and enhanced the lives of at least 350 million people during the last 100 years.

Yet few will be aware of the prominent role played by a Perthshire-born, Aberdeen-educated scientist in the development and production of insulin, one of the most significant achievements in the history of medical research.

John Macleod, a beetle-browed, intellectually brilliant young man from Dunkeld, was at the forefront of the trailblazing work which transformed the battle against diabetes, though not without years of trials and research and disappointments and disputes.

Soon after his birth in 1876, his clergyman father, Robert, was transferred to the Granite City and it proved a seismic move for the whole family.

The youngster, who always adopted the approach that genius was an infinite capacity for taking pains, attended Aberdeen Grammar School and subsequently entered Marischal College at Aberdeen University to study medicine.

However, it was only once he had moved Canada that he forged the partnerships with colleagues which yielded prodigious rewards in the early 1920s.

Challenges, camaraderie and controversy in Canada

There are different perspectives on Macleod’s personality and how he interacted with others. He didn’t suffer fools gladly and was always the last person out of the laboratory in his early days while he was pouring himself into his work.

Averse to getting involved in student high jinks in Scotland, he continued to pursue an academic career with a commitment and dedication which made him a great scientist, but not always the easiest human being to deal with in his day-to-day business.

The driven Scot became director of physiology at Toronto University, where he immediately took a keen interest in research on patients with diabetes.

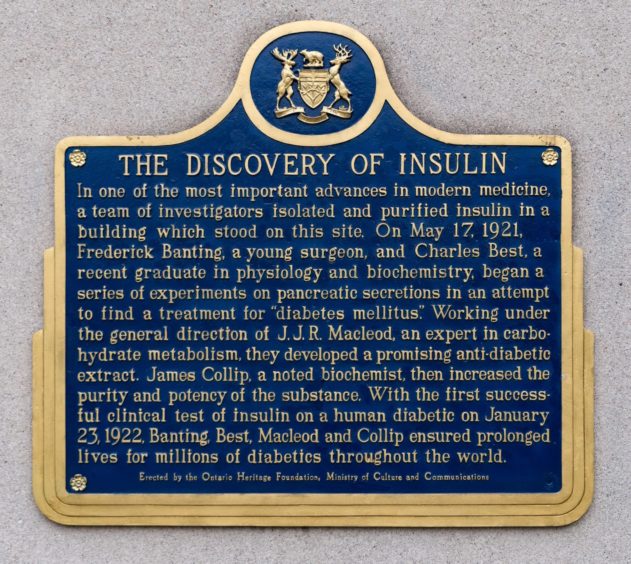

Insulin was developed during his time there in 1921, after he had engaged in groundbreaking work with students Frederick Banting and Charles Best.

Following their collaboration, Macleod received a Nobel Prize along with Banting, although he and the latter subsequently fell out over their contrasting claims of who had contributed most to the discovery.

Who did what and when did they do it?

At the end of 1920, the well-respected Macleod was approached by Banting, a young Canadian physician, who had nurtured the idea of curing diabetes using an extract from a pancreas whose functioning had been disrupted.

At first, Macleod was not persuaded by this argument, because – unlike Banting – he knew about unsuccessful experiments in this direction which had been carried out by other researchers. He considered it was more likely that the central nervous system performed a crucial role in regulating blood glucose concentration.

However, even though Banting had virtually no experience of physiology, he managed to convince Macleod to lend him laboratory space during a vacation in Scotland.

In addition to the laboratory, the Scot provided experimental animals and his student Charles Herbert Best, who worked as a demonstrator.

It was Banting and Best who achieved a notable breakthrough: they isolated an internal secretion of the pancreas and succeeded in reducing the blood sugar level of another dog, whose pancreas had been surgically removed.

The plot thickens as bad blood develops

On his return from a vacation, Macleod was surprised by the findings and expressed initial doubts about the results, but this sparked a furious row between the two men.

They argued bitterly, but Banting accepted Macleod’s instruction that further experiments were required before they could reach any definite conclusion, and even convinced Macleod to provide better working conditions and give him and Best a salary.

The next stage of their research was successful and the trio started to present their work at scientific meetings, which gradually built up momentum and publicity.

Macleod was a far better orator than his associate and Banting came to believe that he wanted to take all the credit for their collaborative efforts. But this notion was nonsense, as was demonstrated when the results were published in the February 1922 issue of the Journal of Laboratory and Clinical Medicine.

Macleod actually declined co-authorship because he considered it was Banting and Best’s work: hardly the attitude of a man who desired to hog the limelight.

A mixture of progress and paranoia in the laboratory

Despite their success, there remained the issue of how to get enough pancreas extract to continue the experiments.

But together, the three researchers developed alcohol extraction, which proved to be far more efficient than other methods.

This convinced Macleod to divert the whole laboratory to insulin research and to recruit the biochemist James Collip to help with purifying the extract.

The first human clinical trial was unsuccessful.

Banting was insufficiently qualified to participate and felt sidelined the longer the work advanced.

By the winter of 1922, this fragile character was certain that all Macleod’s colleagues were conspiring against him and Collip, who was increasingly frustrated with the tension in the laboratory, threatened to leave because of the strained atmosphere.

Yet, amid all this recrimination and rancour, there was stunning progress.

In January 1922, the team performed the first successful clinical trial, on 14-year-old Leonard Thompson and it was soon followed by others.

Macleod’s presentation at a meeting of the Association of American Physicians in Washington on May 3 1922 received a standing ovation from the audience, but Banting and Best refused to participate in protest.

At that time, demonstrations of the method’s efficiency drew huge public interest, because the effect on patients, especially children with type 1 diabetes, who until then were bound to die, seemed almost miraculous.

Macleod was always proud of his part in the process. But, perhaps understandably, he had grown weary of the egos battling for supremacy behind the scenes.

A return to his roots for the pioneer

He returned to Scotland in 1928 to become Regius Professor of Physiology at Aberdeen University and later became Dean of the University of Aberdeen Medical Faculty.

He died in 1935 and is buried in Aberdeen.

There is also a plaque near his old house although, as somebody who never sought the limelight, his name might be better known in Canada than it is in his homeland.

However, the Macleod Centenary Group has been set up in Aberdeen to support JDRF in its mission to find a cure for type 1 diabetes.

It comprises a broad range of people across many organisations, including Aberdeen University and Aberdeen FC, who have pledged to mark the centenary by raising the profile of JDRF, awareness of type 1 diabetes and the significance of insulin.

Carol Kennedy, regional fundraiser in Scotland for JDRF, which is the world’s leading type 1 diabetes research charity, said it was important to recognise Mr Macleod’s place in history and use his achievements as the catalyst for making new scientific breakthroughs in the future.

She said: “We want to ensure that as many people as possible realise the vital contribution John Macleod made in helping so many people with diabetes through his pioneering work with insulin.

“The charity exists to find a cure for type 1 diabetes and its many complications. At a global level, our volunteers and staff have already been responsible for raising more than £1 billion to support research.

“But we know there is still a lot of work to be done and the latest projections estimate an increasing number of young people are being diagnosed with this condition.”

In Scotland, it impacts 32,000 people, 6,000 of them children.