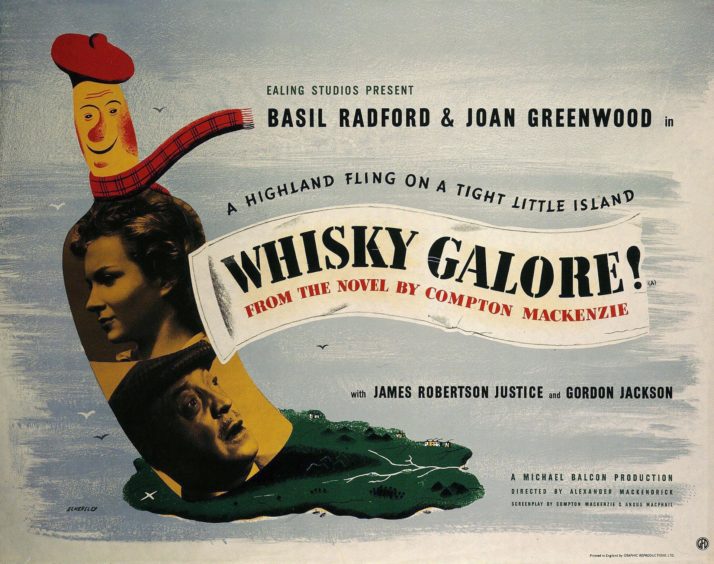

It is one of the most cherished films in the cinematic canon.

But would it have enjoyed such success if the studio bosses had stuck to their original title of Golden Treasure or Liquid Treasure?

You might have an inkling of the movie in question from its French nomenclature: Whisky-A-Go-Go.

But, after it was released to initially modest reviews alongside Kind Hearts and Coronets and Passport to Pimlico in 1949, the work’s story spread through word of mouth and it was gradually acclaimed as a classic tale of canny islanders cocking a snook at bureaucrats.

And even now, Whisky Galore, the Ealing production based on Compton Mackenzie’s novel of the same name is regarded as one of the greatest films made in Scotland.

The author based his book on the real-life travails of the SS Politician, the cargo ship which ran aground off the coast of the Hebridean island of Eriskay in February 1941.

But although Mackenzie used the incident as the starting point for his legacy to the southern isles, he made no cheap jokes at the expense of the islanders and reserved most of his satirical bite for the officials, whether police officers or customs and excise men, who tried to prevent the natives from “rescuing” the 22,000 cases of malt whisky stored in the hold.

In the process, the writer brought the events brilliantly to life – and he helped with the script of the film and even performed in a small role in it – but his account did not tell the whole story of what happened to some of the islanders, including pensioners being threatened and plenty of younger men being locked up in Inverness Prison.

Scotch on the rocks

It was a battle of wills which began after the SS Politician made her way past Islay, then to the west of Skerryvore lighthouse and into the sea of the Hebrides.

However, in difficult conditions with poor visibility, she ran aground on rocks at about 7.40am on February 4, despite the efforts of the wonderfully-named captain Beaconsfield Worthington.

He and the 51-strong crew did their best to extricate the stricken vessel from its plight, but the hull had been breached, copious amounts of water was flooding into the engine room, and the captain ordered the men to abandon ship.

After the radio operator sent two messages – the second of which stated that they were “ashore south of Barra island, pounding heavily” – the men were eventually taken to Eriskay.

They spent the night there, billeted in small groups in the homes of the islanders.

And, despite this happening in the midst of the Second World War, where the message “careless talk costs lives” had been clearly communicated, some of the sailors told their hosts that SS Politician’s cargo contained prodigious amounts of whisky – and also £3m worth of Jamaican banknotes.

It sparked the interest of the islanders and, in a twinkling, some made a decision which placed them directly at odds with the authorities.

From their perspective, the cargo was salvage, and if they could retrieve it, would become finder’s keepers. The die was cast.

A distilled drop of Hebridean history

In the weeks and months ahead, there were all manner of cat-and-mouse activities between the residents and those tasked with upholding the law.

In one corner stood redoubtable local stalwarts such as Donald Hector McNeil and James, Neil and Roderick Campbell; in the other was the formidable Charles McColl, the Lochboisdale customs officer who was directly answerable to the area’s surveyor of His Majesty’s Customs and Excise, who was based in Portree, Ivan Gledhill.

McColl, in particular, lived up to PG Wodehouse’s definition: “It is never hard to tell the difference between a Scotsman with a grievance and a ray of sunshine.”

Under cover of darkness, the islanders rowed out to the wreck, scrambled over the side, using rope ladders, and took hundreds of cases of whisky from the hold. These were hidden in baby’s prams, cupboards, in fields, attic boxes….anywhere they could be stashed. And if they couldn’t be hidden, they could always be drunk.

Hardy souls even travelled from other islands such as Barra, the Uists and Lewis when they learned about the liquid cache, and although the chief salvage officer, Commader Ivo James Kay, arrived at the scene of February 8, he could do little to stall the raids on the SS Politician as word spread about its giant trove.

McColl, though, was implacable. As he and Gledhill stepped up their hunt, he made it clear he wanted any offenders to be charged, not under the common law of theft, but under the far more punitive Customs and Excise Act.

Roger Hutchinson, the author of the book Polly, which covered the whole issue, said: “He wanted them not to be treated as pilferers, but as full-blooded looters of His Majesty’s Treasure; a charge which, in wartime, would be tantamount to treason.”

More than 30 men ended up on trial in Lochmaddy

Searches were carried out across properties, not just on Eriskay, but on a range of crofts in South Glendale – virtually the full extent of the village on South Uist. But despite carrying out extensive investigations, which continued into June, they seemed to retrieve more pieces of kitchenware, cloth and fire-fighting apparatus (from the ship) than cases of Scotland’s national drink.

One of the police reports said: “Spirits were found, but there was abundant evidence that many of the goods had been hurriedly unearthed.

“Attempts to trace the places to which the goods had been removed suggested they had been taken by boats either to a more remote part of the coast or to the small islands in the vicinity. The sites where goods had been removed were frequently in the middle of growing crops.”

Eventually, 32 men from South Uist and Eriskay appeared in person at Lochmaddy Sheriff Court between June 10 and 13.

As Mr Hutchinson told me: “They entered pleas of not guilty, not out of any capricious bid to escape punishment, but because they genuinely believed that, whatever wrongs they might have committed, theft from the SS Politician was not among them.”

The courts, though, took a different view. As did McColl and Gledhill.

Many were sent to Inverness Prison after the trial

There was a frisson around the courtroom when Charles McColl gave evidence to the court at Lochmaddy in June 1941.

He testified gravely, in fastidious detail, how the accused had stolen goods from a ship which was still seaworthy. He made it clear that there was no room for levity in treating the islanders who had carried out the theft of whisky and other items.

The sheriff agreed and the punishment was more than had been expected by most of the 32, who were mostly aged between 25 and 50, but included one 82-year-old.

Only one of the group was found not guilty. Nine others were dismissed from the court with their cases not proven. Proceedings were dropped against one teenage boy from South Glendale, following a report prepared by the local minister.

But his elder brother, who had also been involved, bore the brunt and was sentenced to 20 days’ imprisonment. And so were 18 others, who were ordered to be taken down to Inverness Prison, more than 200 miles away by sea and land.

With the exception of a couple who escaped with minor fines, 19 men were put behind bars for periods ranging from 20 days to two months.

The officials still pressed for harsher punishments

All these events happened out of the public gaze. Given the restrictions on reporting in wartime, the privations suffered by the SS Politician hadn’t appeared in print or on air.

Well, for the most part. However, after the ship ran into the rocks, the story spread that the Nazi propagandist William Joyce – better known as Lord Haw-Haw – had broadcast the “news” she had been lost with all hands.

The one British newspaper which covered the trial was the Highland News, which mentioned on June 24 that “a number of men had appeared in Lochmaddy to answer to a charge of theft of whisky and other articles.”

In other circumstances, it would have been a world exclusive. But the name of the ship wasn’t mentioned, nor any of the relevant details: in wartime, revealing the details of British citizens removing items from a stranded UK vessel was considered unpatriotic.

That should have been the end of the affair, but Messrs Gledhill and McColl were dissatisfied with the verdicts. The former wrote to Procurator-Fiscal John Gray to protest about their leniency and followed that up with correspondence to London.

He described the sentences as “quite inadequate to act as a general deterrent to the population of these islands, who in my opinion, will probably seize their next opportunity to indulge in further looting and damage.”

The end of the story…and the inspiration for a novel

Eventually, the chief constable of Inverness-shire, William Fraser, grew tired of all the allegations that he and his men had not co-operated properly with the customs officers.

As Mr Hutchinson wrote: “The authorities in the Highlands and Islands, not to say those down in London, were heartily sick of the tawdry business of the SS Politician.

“Nobody else from the southern isles would gain a criminal record as a result of their association with the stricken ship.”

Mr Gledhill finally went away with his tail between his legs. Mr McColl was viewed with suspicion and resentment for the rest of his days on Eriskay.

As for the captain of the SS Politician, Mr Worthington was cleared of all blame and returned to sea, in charge of SS Arica, which was sunk by a U-boat in November 1942.

But while that might have been the end of the true-life story, the whole case intrigued a writer in his 60s who was living on Barra at the time.

In 1947, Compton Mackenzie’s Whisky Galore was published, the book captured the public’s imagination, and then Ealing Studios came calling for a screenplay.

And the rest, as they say, is up there on the silver screen for posterity.

The film was especially popular in France

Roger Hutchinson was in France more than a decade ago when he realised the universal appeal of the film Whisky Galore.

After talking to a few of the local people on his travels, he was asked to introduce a special screening of the Ealing comedy and, with the help of an interpreter, offered a few thoughts on the 1949 movie.

As he recalled: “That was in 2008 and there must have been 20o residents in the hall and they sat enthralled throughout the film – and then they cheered it at the end.

“It showed me that the humour of these islanders had struck a chord and the idea of cocking a snook at authority had also appealed to them. The film endures.

“There were no crusading Customs and Excise officers in the book or the film. No pensioners were threatened with severe legal action and nobody was sent to jail.

“But, in his inspired flight of fancy, Compton Mackenzie took a rough and sober canvas and painted brilliantly upon it with primary colours.”

Polly: The True Story Behind Whisky Galore is published by Mainstream.