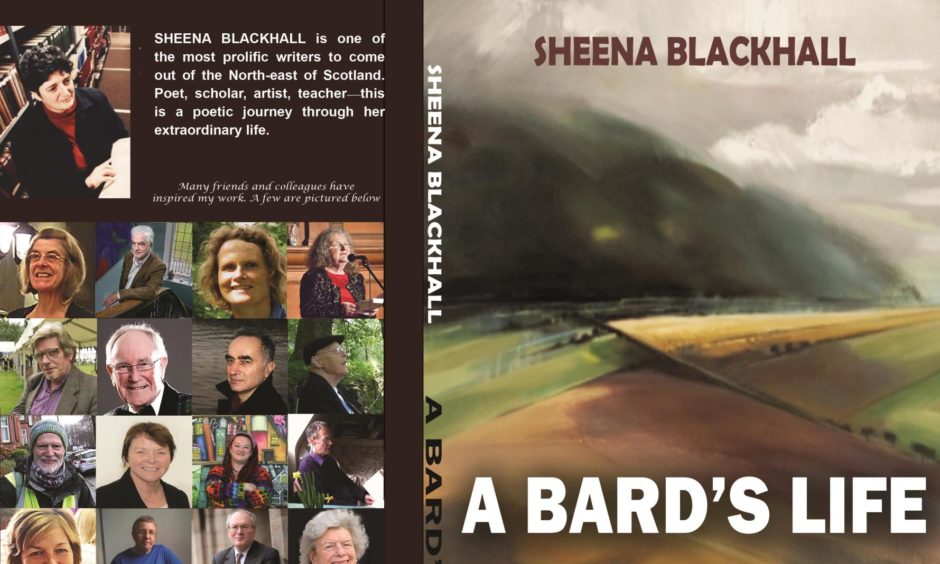

She is one of the most well-known faces in the north-east for her distinctive poetry and prose and constant championing of the Scots language.

But Sheena Blackhall’s life has encompassed far more than words and music, culture and academia, as she has revealed in an often harrowing new autobiography.

It details how, while working as a student teacher in 1966, she was attacked by a pupil who was a survivor of the Aberdeen double-murderer James Oliphant; an ordeal which led to her trying to take her own life and being rushed to Woolmanhill Hospital.

A Bard’s Life also relates how Ms Blackhall was placed under emergency section in the Buchan Ward at Cornhill [psychiatric] Hospital in 1987 and released after 10 days into the care of her elderly parents, who helped her recover from a traumatic period.

The work, which is being launched this month, features her recollections of the many positive experiences and plaudits which the 73-year-old has amassed on her travels.

Yet she hasn’t flinched from chronicling the grimmer chapters on her journey through Aberdeenshire and Aberdeen to such destinations as the Smithsonian Institute in Washington – where she and a colleague survived a sniper’s bullet on a trip to a mall.

Chaos in the classroom sparked a near-tragic outcome

In the early 1960s, Aberdeen was rocked by the murder of two children, June Cruickshank, six, in 1961 and George Forbes, seven, in 1963.

Eventually, following the biggest-ever investigation by police in the Granite City, a 39-year-old labourer, James John Oliphant was arrested and charged with the killings and subsequently sent to Carstairs State Mental Hospital [where he died in 1988].

Officers had been questioning him about an attack on another boy when he broke down and confessed to the full extent of his crimes.

A matter of three years later, Sheena Blackhall, who was just a teenager herself, was starting life as a student teacher when she was the victim of a shocking incident.

In the book, she has written: “I was flung to the floor by a child survivor of an attack by the murderer Oliphant. That night, I made a suicide attempt.

“I was revived at Woolmanhill casualty and referred to Dr J D Gomersall at the Ross Clinic in Aberdeen for counselling.”

Ms Blackhall spoke further about the incident to the Press and Journal this week.

She added: “[The boy] was very disturbed, smashing things, and the management were trying to get some help for him. Because he had been molested and traumatised, his family had sent him to ju-jitsu classes.

“When I leaned forward to grab his arm to stop him smashing another pupil’s windmill, he used my forward stance to fling me. I landed on my back, not injured but winded, and the class was in uproar. That was on the Friday. I was in hospital in Saturday [having her stomach pumped] and back in the school on Monday, but not in class.

“The head had concocted some story about wanting me to draw a tank of fish because I was supposed to be good at art. But X [the boy] was much more of a victim than me.”

The pride and plaudits behind the pain

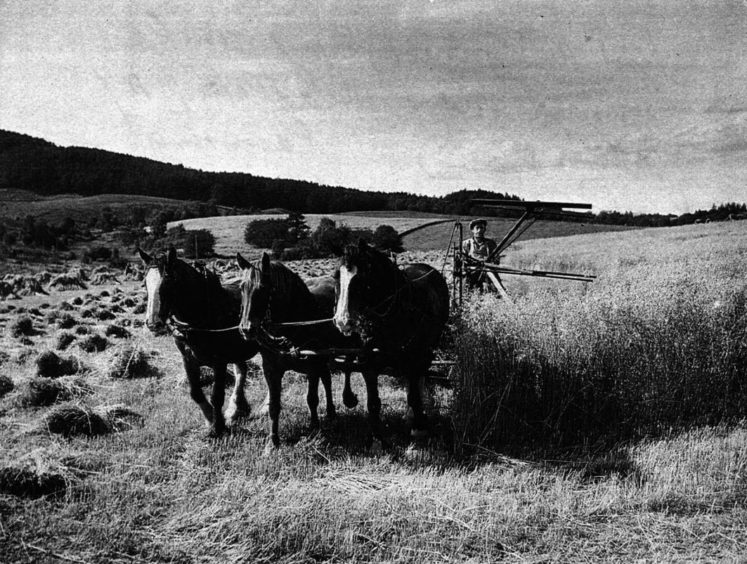

There is no doubting the significant body of work which had been created by Ms Blackhall, who was originally inspired to take an interest in local songs and poems by her maternal grandmother Lizzie Booth of Coull in Tarland.

In 2018, she received an honorary masters from Aberdeen University, a place with which she has always enjoyed a close relationship while becoming one of the most recognisable figures around her roots.

For almost two decades, she has contributed to the work of the university’s Elphinstone Institute and consistently played a part in its annual May Festival.

The Laureation Address for Ms Blackhall three years ago was delivered by lecturer Professor Thomas McKean, who is one of the driving forces in enhancing traditional languages and dialects from across the region.

His speech, which was made entirely in Doric, celebrated her myriad contributions to literature and tradition and he said later: “Sheena represents the best of north-east identity and does it with style, confidence, perception and grace.”

Tackling anti-Scots prejudice

Nowadays, given the popularity of her work, it might be difficult to recall the struggles which Ms Blackhall has endured when striving to highlight the Scots language.

As an indefatigable character, she was determined to bring her efforts to a wider public, but it didn’t happen without a plethora of setbacks and a bruising battle not just with cultural officials, but herself.

She said: “In 1987, my work was rejected by Aberdeen Artists Committee again. Then, in May, I was placed under emergency section in the Cornhill and released after ten days, an outpatient, into the care of my parents (my father was 80, my mother 78 and disabled) and they also had care of my children.”

It wasn’t the longest time she had been confined in a hospital bed.

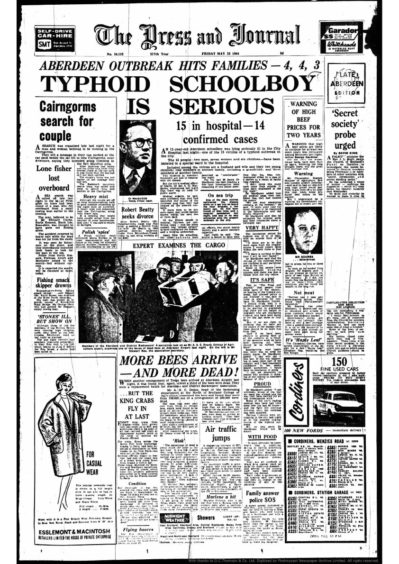

In 1964, during the typhoid epidemic in Aberdeen, an outbreak which attracted international banner headlines and required a lockdown of the area, Ms Blackhall caught the disease and, as a 16-year-old, was isolated in the city’s fever hospital in Urquhart Road.

As she has written: “For the first time, I experienced a kind of panic, a fear of incarceration that was claustrophobic in its intensity, an awful confined crushing sense of restraint.

“I wanted out and I wanted out straight away.

“Other patients, well enough to walk, crawled around each other like drugged locusts, eyes swollen with sleepless nights, strangers forced together by disease.

“At night, the moan and sob of the sick, delirious women rose and fell in the ward like the eerie wind in a dark tunnel, the tight-locked windows yielding neither the sun nor rain.

“The longer that I stayed in the ward, the less I resisted captivity. I slept, I ate, I slept and every waking moment was planned for me. Soon, it was the world beyond the glass that was unreal. It took a long, long time to build up the strength.”

Battling for the Scots language

Sheena Blackhall has discovered both the positive and negative impact of writing at such a prolific rate. It’s her way of reacting to life and she considers it “therapeutic”.

But, while the future of Scots is once again generating publicity and provoking debate, she gave me a cautious response when I asked if she was optimistic about the future.

She said: “[Such bodies as] The Doric Board, the Elphinstone Institute, The Burns Federation, Scots Radio, Rymoor Books, the work of our local writing festivals shows there are a long line of shoulders building the pyramid.

“Individual schools do great work promoting Scots. Sadly, Education Scotland removed all its material at a stroke a couple of years ago, history, language, song, story, the lot.

“[It was] like smashing a mirror. But the splinters pop up here and there.”

A close shave in a shopping mall

Ms Blackall has been happy to travel around the world, promoting the often rich and lyrical qualities of the language which she cherishes.

But the campaign hasn’t always been without its problems – and danger.

She recalled: “In the summer of 2003, I represented Scotland, through the Elphinstone Institute, storytelling and singing in Washington as a guest of the Smithsonian Institute, accompanied by [folk singer and piper] Stanley Robertson.

“We were chatting in a mall when a sniper shot the disposable cup out of his hand.

“He said: ‘They surely dinna like traivellers here either!”

Writing and dealing with Covid

Ms Blackhall has kept herself busy during the Covid pandemic. Unlike most of the rest of us, this woman already knows all about living under lockdown regulations.

Her new book is painfully honest, but features a wealth of poems, stories, reminiscences and recollections from her past. As the renowned Scottish author Alan Spence said in the foreword: “Sheena being Sheena, it’s no ordinary telling of her extraordinary story.”

The author told me she doesn’t make any grand claims and has never been one to “gallivant”, but she has clearly found the experience cathartic.

As she said: “My way of reacting to life is through the medium of poetry or short story. Some of it is descriptive, some is confessional, and I can ‘factionalize’ events by writing through a different age or gender, like wearing masks.

“The page is my confidant, my best friend, my listener. Anybody can write a biography….we’re all built like a stick of rock with LIFE stamped through it.”

‘The bairns aa luve their Doric’

In terms of responding to the Covid restrictions, she replied in the language which she has nurtured for decades: “It’s bin life as usual. The birdies are enjoyin the peace an quaet in the gairden, we even hid a roe deer chawin the girse.

“I’ve enjoyed Zoom sessions wi skweels. The teachers set them up and I can steer the bairns up tae high doh and nae worry aboot calmin them doon eftir.

“They aa luve their Doric”.

It’s true.

And nobody has toiled harder to bring that to fruition than Sheena Blackhall.

The book can be purchased at: https://www.rymour.co.uk.