He was the man who spent more than 50 years interviewing and recording for posterity the memories of Scottish veterans of the First World War.

Jock Duncan, the acclaimed north-east folk singer, who has died aged 95, transcribed numerous recordings, word for word, on his old manual typewriter, creating a unique archive of the stories of the many youngsters who left the farms of Aberdeenshire, Angus and Perthshire for the fields of Flanders and France and the shores of Gallipoli.

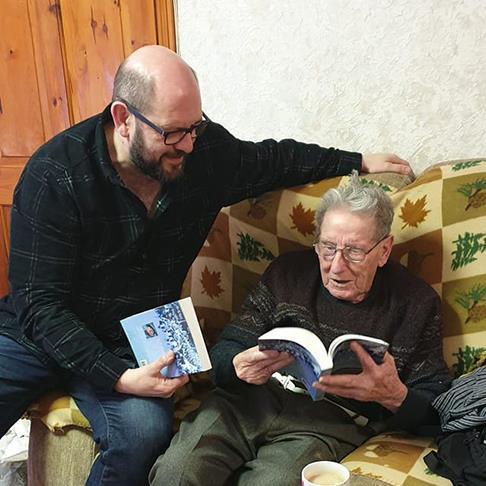

Friends and colleagues have paid tribute to somebody they regarded as a “national treasure twice over”, both for his rich musical contribution, which has earned him inclusion in the Scottish Traditional Music Hall of Fame, and his tireless work on ensuring the voices of the Great War were collated in his book Jock’s Jocks.

Jock offered support and inspiration to generations

Frieda Morrison, the director of Scots Radio and one of the members of the Doric Board described his contribution to his country’s history and heritage as “immeasurable”.

She said: “Jock has been one of the most treasured members of the Scottish cultural world for many years. He has been a support and an inspiration to generations of traditional singers and was always encouraging and supportive to the many people who called on him for advice and information.

“He was that important link in the chain that connected us with so many aspects of the past, that had relevance to the present and the future – he jist didna hud back.”

That view was echoed by Sheena Blackhall, who is often described as the “Queen of Doric” and ‘ackowledged in taht language’ the impact which Mr Duncan had made.

She said: “Ma granny’s sister Kate an her man, the Watts o New Deer fermed, (an still own) Fadlydyke Ferm.

“I larned cornkisters [bothy ballads] frae ma granny jist as Jock wid hae dane frae his fowk.

“It is a land steeped in sang and Jock Duncan wis a great champion o the Doric, generous tae a faut, an he weel deserved the mony competitions he won in the Bothy Ballad Tradition.

“He is a great loss tae the culture o the Nor East, a muckle stane caad inno the dyke that’ll be ill [hard] tae replace.”

Iona Fyfe, the award-winning Huntly singer, admitted she had been very nervous before performing in front of Mr Duncan several years ago.

She said: “I remember Jock judging me at the Turra Bothy Ballad competition. I was terrified. It was like singing for bothy ballad royalty.

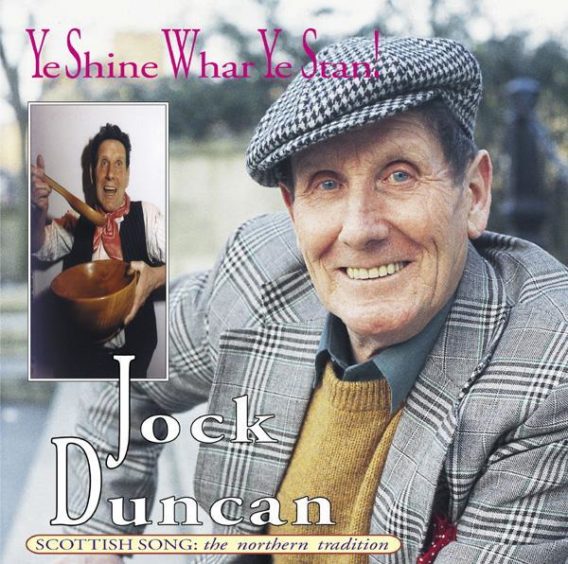

“I spent ages trying to find his album Ye Shine Whar Ye Stan.

“Then I finally found it at a folk club CD sale in Haddenham in Oxford!

“People loved him all over the world.”

A lad o’ pairts who thrived on the farm

Mr Duncan, who was born on the farm of Gelliebrae, by New Deer in 1925, grew up at a time when horses were still in daily service and thrived in the agricultural domain.

By the age of ten, he could drive a horse and plough expertly, an experience that he subsequently put to powerful use in performing his famed Tradesmen’s Plooing Match song, complete with imaginary livestock.

Music and song were an everyday part of the Duncan household.

Jock’s mother was a fine pianist who organised musical sessions in the front room and accompanied the fiddlers she invited.

His older sister Marion sang and brother Jimmy played the fiddle.

A regular visitor to these sessions was the celebrated John Strachan, a local gentleman farmer who went on to sing on BBC broadcasts and appeared on the 1951 People’s Ceilidh, a milestone event in the Scottish folksong revival.

Mr Duncan remembered, as a youngster in the 1930s, singing along with Mr Strachan and learning ballads such as Bonnie Udny and Rhynie from him.

He was also assisted by George Kidd, the grieve at the neighbouring farm, and his schoolteacher at Fyvie.

The information these individuals passed on, as much as the songs, added to the richness of the youngster’s recitations at concerts across Scotland.

Following service with the RAF in the Second World War, he briefly returned to farming and formed The Fyvie Loons and Quines bothy ballad concert party before starting a new job with the Hydro Board which took him first to Caithness and thence to Pitlochry where he said later he was in his element.

Jock became a recording star in his 70s

This redoubtable character never lost his Doric speech or his love of ballads and, in 1975, he entered and won the bothy ballad competition at Kinross Festival, which proved the launch pad for a long run of similar successes at folk festivals where his enthusiastic and entertaining renditions became the stuff of legend.

In 1996, at the age of 71, Jock recorded his first album, Ye Shine Whar Ye Stan!, followed five years later by Tae the Green Woods Gaen.

He was awarded a Herald Angel for services to ballad singing at the Edinburgh International Festival in 2000.

This formed part of a unique family hat-trick with his sons Ian and Gordon receiving the same award, Ian for his work with the Vale of Atholl Pipe Band and Gordon for his solo piping and composing talent.

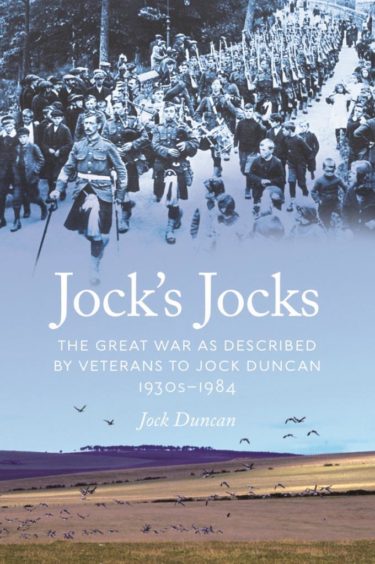

The book was a labour of love for Jock

Mr Duncan realised that the memories of so many north-east soldiers might be lost forever unless he worked to gather them together.

During a long period from the 1930s to the 1980s, he amassed the reminiscences of 59 men from 14 regiments, including the Gordon Highlanders and the Black Watch, and these were published by National Museums Scotland.

They captured the sense of pride, fear, frustration and other emotions which were felt by the men in the trenches, who had often travelled abroad for the first time.

They also caught the earthy humour and Doric language which was cherished by Mr Duncan during his long life and were later turned into a play.

One of the Gordons saw the Red Baron’s death

Running through the soldiers’ first-hand reports of Mons, Gallipoli, Loos, the Somme, Ypres, Passchendaele and Cambrai are harrowing descriptions of the unprecedented human sacrifice of the 1914-18 conflict.

Not even the famous Christmas truce of 1914 offered a respite from the blood and guts.

According to Alford man Jimmy Reid, of the 6th Gordons, one of the duties of the ceasefire was to “collect aa the deed bodies an beery them… that wis nae picnic, some just bits and hid to be collected into bags an’ the stink beat hell”.

However, another member of the regiment, A MacEwan of Banff, was among the first to discover the body of the famous Red Baron [von Richthofen] in 1918.

He recalled: “We had just been relieved in the front line by the Black Watch and we were going to our huts for a rest when it happened. It was just dawning in the early morning when we watched the Red Baron’s planes coming over.

“They came at us with their machine guns blazing, but we took cover in the ditches and fired back with our rifles.

“Suddenly, we saw two of our planes come at them and one of them got the Red Baron’s plane. It came down and crashed beside us. I went over and saw him sitting there as dead as a doornail. I was later mad at myself for not taking away a souvenir off it.

“We learned later on that the pilot who shot him down was a fellow called Ron Brown. Later in the day, the British came over with 12 planes and dropped wreaths of flowers on the spot where he was killed.”

Mr Duncan later said he had been surprised by how calmly the troops spoke of the myriad horrors which they had all endured throughout the hostilities.

But he added there was also a gallows humour to many of their accounts. John Will, of the 5th Gordon Highlanders, summed up the stoicism in their ranks.

The Turriff man said: “I got my callin up papers after I hid been a eer [year] in France.”

Jock’s Jocks is published by National Museums Scotland.