When the Art Deco Capitol cinema was unveiled in the midst of The Great Depression, it was dedicated to the people of Aberdeen.

The 1930s were characterised by astronomical unemployment, and widespread financial ruin and despair, in what came to be known as “the devil’s decade”.

But in dire times, cinema provided escapism from the hardships of daily life.

During the 30s, five new cinemas were built in Aberdeen in the exuberant Art Deco style.

But when the Capitol opened in 1933, people questioned the scale of such a project during the slump.

Aberdeen Picture Palaces Ltd said they had modernised the old saying “in times of peace prepare for war”, and created their own motto: “in times of depression prepare for prosperity”.

The directors said they had not built the cinema for today, but for “the people of Aberdeen, their children and their children’s children”.

It was a symbol of hope – cinema was soaring.

But with the rise eventually came the fall.

And like many of Aberdeen’s old cinemas, the exciting glamour of the Art Deco cinemas faded too, existing now only in the memories of Aberdonians.

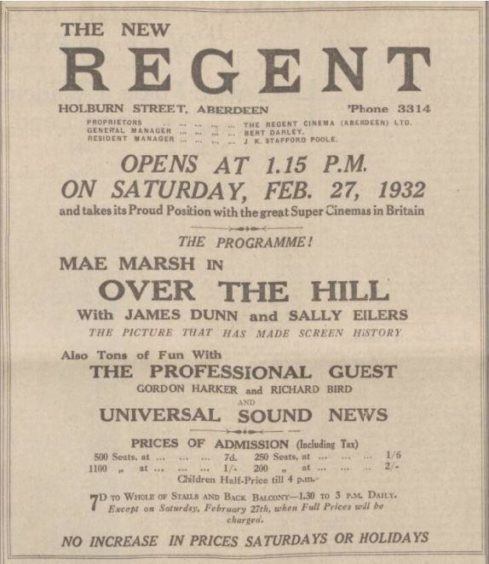

The Regent

It took only seven months from the laying of the foundation stone to the doors of the Regent Cinema opening on Justice Mill Lane in 1932.

Designed by renowned Aberdeen architect T Scott Sutherland – who specialised in cinema design – the unusual Art Deco meets Baroque style theatre stood out for its “dignity and beauty”.

Built on the awkward, sloping site of the former Justice Mill, engineers had their work cut out incorporating the 30ft height difference and diverting the old mill pond.

The enormous task of excavating the site and erecting huge beams pushed the cost to £32,000 (£2.6 million in today’s money).

Aberdonians couldn’t quite believe the feat was achievable and upon completion, one commentator said “from whatever angle one views the structure, it pleases the eye”.

The Regent’s handsome granite facade faced Holburn Street and featured striking bands of terracotta and neon lighting.

Three sets of double doors led patrons into a spacious foyer of polished oak panelling with silver detailing and the auditorium beyond, which had a 2100 capacity.

A neutral color scheme with highlights of blue, red and brown complemented gold velvet seating and hand-welded balustrades.

It was equipped with the latest sound technology from America for “talkies” and although the Regent was considered the cutting-edge of cinema in Aberdeen, a stage was also constructed “just in case of the revival of vaudeville“.

The Regent’s inaugural showing was Over The Hill featuring Mae Marsh and was Marsh’s first film that featured sound.

Just a few years after opening it changed ownership, and again in 1940 when it became the Odeon.

In 1947, the capacity was reduced to 1865 people and a renovation in 1974 converted the cinema into a three-screen operation with one large auditorium and two mini screens.

The cinema closed in June 2001 and became a fitness studio, today run by Nuffield Health.

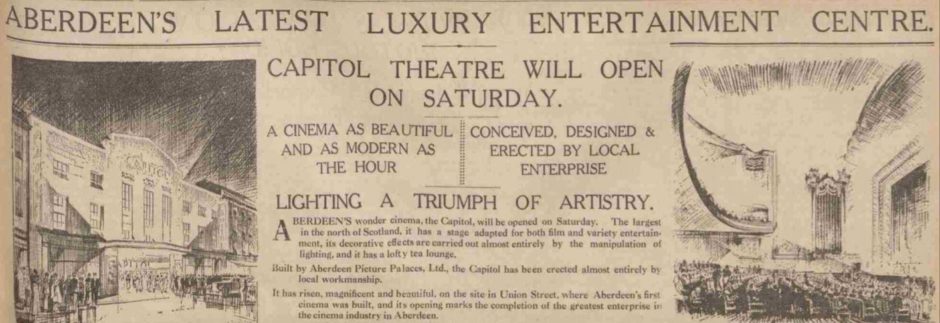

The Capitol

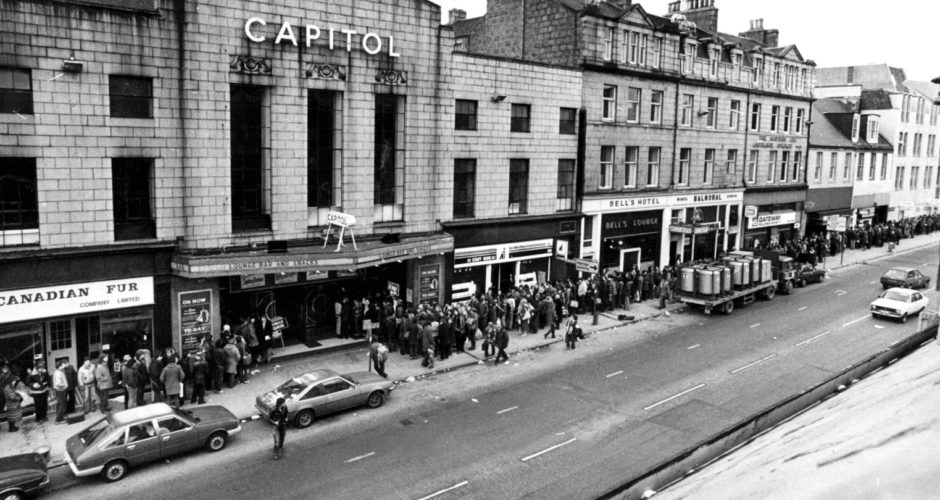

The Capitol cinema arose from Union Street “magnificent and beautiful” when work was completed in February 1933.

Billed as an Art Deco “triumph of artistry”, the Capitol was built on the site of Aberdeen’s very first cinema, the Electric Cinema.

Designed to “please the eye and charm the ear” in the spirit of pure entertainment, it featured the latest advances in cinema and theatre.

A pioneering lighting system, a mezzanine tea lounge, a Compton theatre organ and the biggest cinema auditorium in the city made the Capitol “as modern as the hour”.

The handsome Rubislaw granite facade reflected the architectural lines of Union Street, while a contrasting bronze canopy created a striking entrance.

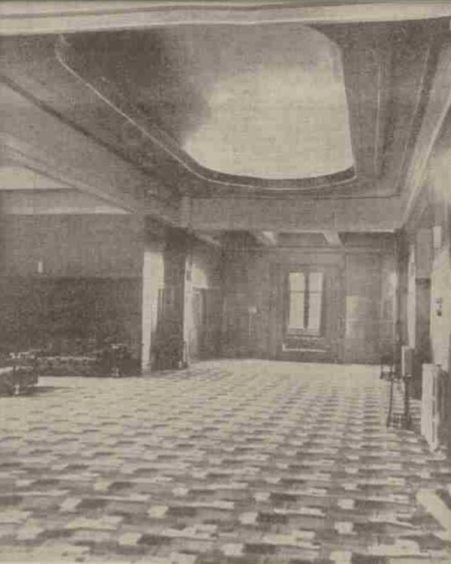

Once inside, the elegant and understated interior was an Art Deco dream featuring terrazzo flooring, blush-coloured mirrors and walnut panelling.

A sophisticated restaurant, decked in a colour scheme of purple and gold, overlooked Union Street.

Visitors were treated to a soda fountain, a musical quintet, a polished oak floor for dancing and a ladies’ cosmetic room.

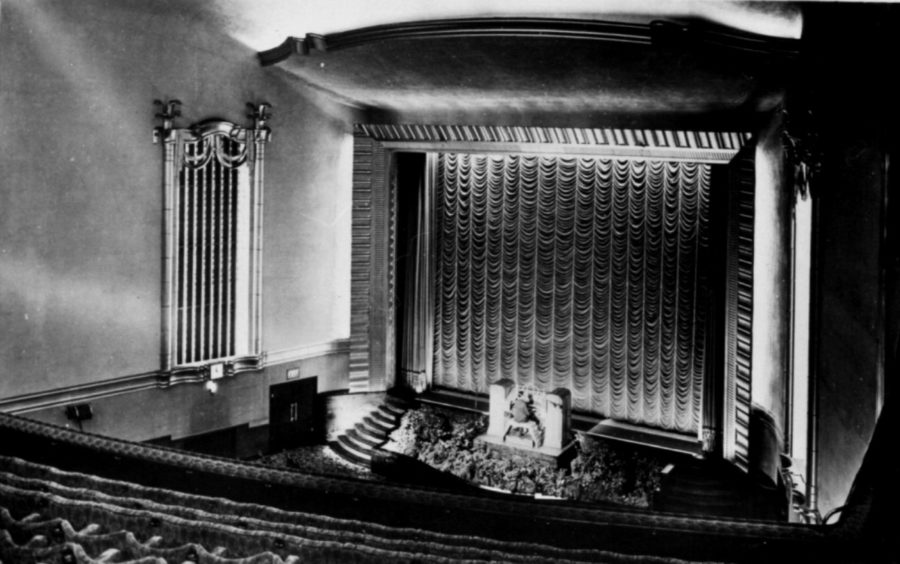

And downstairs, the main auditorium had sweeping, curved lines, decadent silver leaf decoration and delicate plasterwork.

Underneath the embellishments, the structure featured the heaviest steel beam that had been used in construction in Aberdeen at that time, weighing in at 38-tonnes.

And the jewel in the Capitol’s crown was “the organ that disappears”.

The Compton organ was described as being capable of “faithful imitation of human and other sounds”, as well as regular music.

A hydraulic lifting system meant the organ – and attached organist – could be raised and lowered from the orchestra pit below, as if into thin air, during performances.

And the Holophane lighting system was the first of its kind in the UK allowing different coloured lights to be projected during performaces.

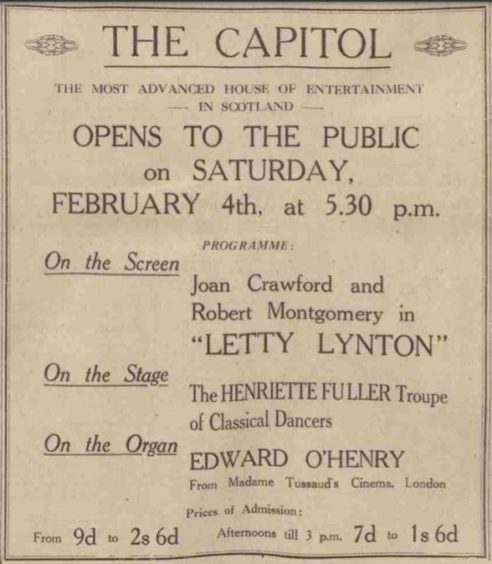

The opening ceremony of the “most ambitious enterprise in Aberdeen cinema” saw proprietors Mr and Mrs Hay unlock the premises with a gold key.

Guests admired the quiet dignity of the vestibule, and the occasion was especially significant as “it had been achieved by Aberdeen brains and Aberdeen workmanship”.

The public queued for two hours around the corner in heavy rain desperate to get a first glimpse of the opulent addition to Union Street.

And to see the first film to be shown there – Letty Lynton starring Joan Crawford and Robert Montgomery.

An all-singing, all-dancing debut, the film was accompanied by a London dance troupe and Edward O’Henry on the organ.

As cinemas went into decline in the 1960s, the Capitol stopped regular film showings and became better known for hosting rock concerts.

A myriad of stars tread the boards over the decades until the theatre’s shock closure in December 1997.

With no prior announcement, it was the guitarist of a Beatles tribute band that informed stunned revellers their final number, Let It Be, would be the last song to be played live in the Capitol.

The Oscars bar remained open and the original Art Deco features remained unscathed until the venue was transformed into Jumpin’ Jaks nightclub in the early 2000s.

It too closed in 2009 and the old venue sat empty, derelict and damaged by water ingress, until developers moved in in 2013.

The Capitol has since been restored to its former Art Deco glory as an office development, with original features like the canopy entrance, light fittings and motifs saved and restored.

The Astoria

When the avant-garde, Art Deco Astoria opened in Aberdeen in 1934, it was a trailblazer for cinema design in Scotland.

It was a “super cinema” built on a vast site called Central Park in Kittybrewster in the days before multiplex and – at a cost of almost £3 million – no expense was spared.

Unmistakably Deco, the cinema was another the vision of architect T Scott Sutherland.

His plans described how the imposing granite facade was “built on sumptuous lines”, while inside, viewers would enjoy the latest in screen technology.

Everything for the luxurious Astoria, except the organ sound equipment, was built or handmade in Aberdeen to the tune of £40,000 (£2,927,595 in today’s money).

The whole frontage was electrifying – illuminated day and night in blue, yellow, green and orange neon lighting.

Nicknamed ‘liquid fire’, the spectacular neon lighting continued under the canopy and into the foyer.

It was the first cinema of its kind in Scotland to pioneer such a dazzling display.

Stepping into the “lofty and dignified” foyer was like walking into a palace.

In 1934, the average Aberdonian would have felt like a film star sauntering onto a glamourous Hollywood set.

The colour scheme was light pink, ivory and brown to complement the finest walnut wall panelling, while the solid walnut doors were adorned with cast bronze fittings.

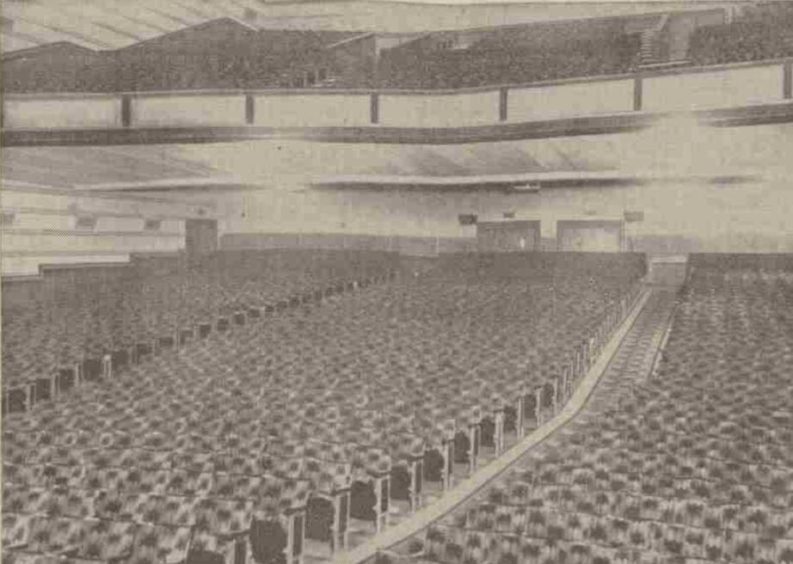

Two miles of green and brown plush, patterned carpet covered the floors, to “harmonise” with the mile of brown and terracotta moquette fabric needed for the seating.

Around 30 tonnes of castings were needed to make 2060 tipping chairs for the main auditorium, and it took 102 local men and women five months to upholster them.

A soft, carpeted sweeping stairway lead to a balcony and lavish lounge, as well as a boardroom and offices.

But the jewel in the crown was the huge proscenium – the archway framing the stage – which was dressed with opulent green curtains and silver screen made of satin.

Debuting the latest developments in cinema lighting, the proscenium featured red, blue and green hues.

These colours could then be blended through a specially-made modern mixer to project hundreds of different shades into the auditorium.

Cinemagoers were in for an audiovisual experience like no other, and when it came to the projector, only the best would do.

Ahead of the opening, managing director for the Astoria Bert Darley said: “Above all, modern cinemas require highly efficient film equipment.

“The sound-recording system is the first of its kind to be installed in Scotland.

“It is of the RCA (Radio Corporation of America) type, with high fidelity horns and a RCA super-simplex projector.

“The result is that difficult sounds to reproduce, such as the crumpling of a piece of paper, can be faithfully reproduced.”

In addition to technology, a special feature of the Astoria was a Compton organ – the first in Scotland to be illuminated, and only the second cinema in Aberdeen to have its own organ.

The eye-catching organ was also mounted onto a kind of railway so it could be pulled onto the stage.

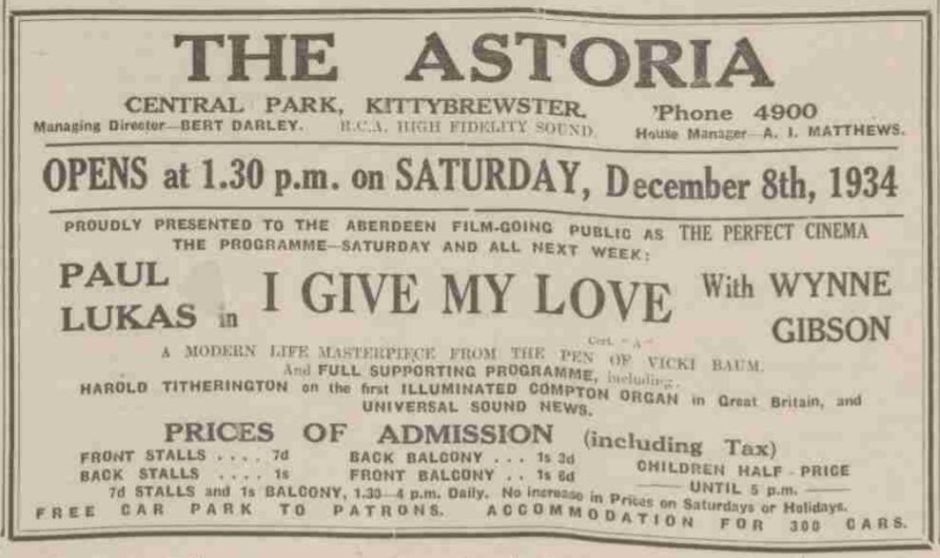

Excitement and anticipation built ahead of the Astoria’s opening, but it wasn’t a silver screen starlet who performed the opening ceremony on December 8 1934.

Instead, the grand honour was bestowed upon 72-year-old Robert Gibb of nearby Cattofield Terrace.

The local pensioner took such an interest in the Astoria that he visited the building site daily – including Sundays – since work began.

The first film shown was ‘I Give my Love’, starring Paul Lukas, with the Astoria’s Harold Titherington accompanying on the illuminated organ.

Prices of admission (including tax)

Front stalls . . . 7d Back balcony . . . 1s 3d

Back stalls . . . 1s Front balcony . . . 1s 6d

– Children half-price until 5pm –

7d stalls and 1s balcony, 1.30-4pm daily,

no increase on prices on Saturdays or holidays

The cinema went from strength to strength, and the Astoria provided other-worldly escapism during the war years.

It escaped a near-miss itself during the Aberdeen Blitz when a 500-kg explosive detonated just west of Kittybrewster Station on the other side of Great Western Road.

But with the rise came the fall – cinema dramatically fell out of fashion in the 1960s.

The Astoria, despite its innovations, wasn’t immune.

Like many other palatial picture palaces in Aberdeen, it closed in August 1966 before reopening two weeks later as a bingo hall.

But just four months later it closed for good, to be replaced with a shopping precinct.

Little over 30 years after the state-of-the-art Art Deco masterpiece was built, it was pulled down stone by stone, girder by girder in 1967.

Stripped of its sumptuous interiors and roof, all that remained was a steel skeleton, before it too collapsed into the dust.

The special organ was offered for sale to nearby Powis Academy, music master at the school Robert Leys, along with 10 senior pupils, dismantled and removed the instrument.

The youngsters traipsed up Great Northern Road carrying organ pipes, but it was another year before it was restored to working order, taking centre-stage in the school’s assembly hall.

Sadly the organ was lost during a devastating blaze when a former pupil set fire to Powis Academy in 1982.

The Majestic

Another T Scott Sutherland super cinema, the modern Majestic was built in 1936 to replace the La Scala.

The Victorian opulence of the La Scala cinema gave way to masculine, Art Deco lines as the Majestic towered over Union Street.

It was described as an instant landmark when it opened, and a building of beauty and efficiency.

The stately structure of Kemnay granite was illuminated at night in neon, and a huge floodlit display sign showed what was on the bill each day.

Cinemagoers were promised to be astounded by the exquisite vestibule which had five sets of double doors, panelled walls and panelled stairways.

Patrons’ feet “would sink into rich carpets” in the green and cream auditorium, where there was row upon row of rose-coloured seats.

The view from the balcony was one of “dignity and simplicity”; the blocks of square seats below were softened by a majestic curved ceiling.

And on the upper floor there was a milk cocktail bar, a soda fountain and a tearoom, as well as cosmetic rooms for the ladies.

Times had changed – no organ or orchestra were incorporated in the build.

Instead, the Majestic was equipped with the best acoustics and modern projecting apparatus, as well as audio provision for the deaf.

And when the 1800-seater cinema opened on December 10, it took the ratio of cinema seats per Aberdonian to one for every seven residents.

The Granite City could boast a higher number of cinema seats per head of population than London.

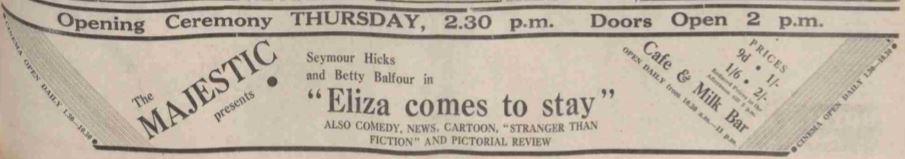

The opening film was “Eliza Comes to Stay” starring Betty Balfour and Seymour Hicks.

People queued for hours on opening day to clap eyes on the latest Deco addition to the city, while an opening ceremony of 1400 guests took place inside.

Its predecessor, La Scala earned a seedy reputation during the war when it attracted street walkers hoping to hook up with soldiers.

And the Majestic’s management were at great pains to emphasise that they would exclude “sordidness” from their programmes.

The Majestic’s existence was relatively short, it wasn’t standing for forty years before it was torn down in 1973 for offices.

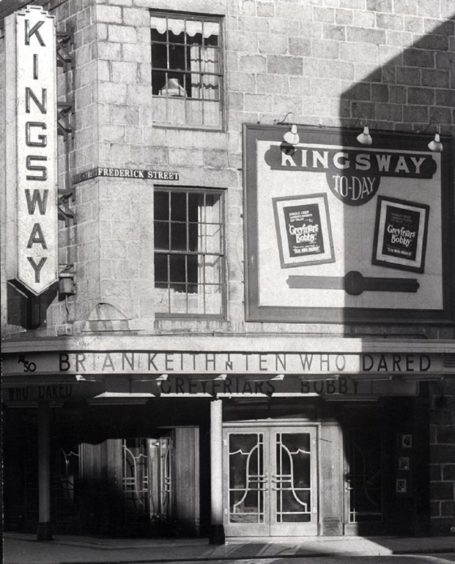

The Kingsway

When the Kingsway was opened by the four Donald brothers in 1939, there were inklings of trouble brewing in Europe.

It was declared that it could be used for “entertainment, education, recreation and relaxation”.

But just a year later it would be packed out with shows raising funds for the war effort.

Nearly 2000 Aberdonians turned up to the ceremony conducted by depute lord provost Milne, a friend of the Donald brothers’ late father, James.

James Donald had set the bar high in Aberdeen’s cinema circles with the family business at one point owning 12 of the city’s 16 cinemas.

He laid the foundation for the Kingsway in 1934, but the project stalled after losing backing.

After Mr Donald’s death, the determined brothers finally brought it to fruition in 1939.

Commending the four businessmen, Mr Milne said it was a cinema that catered for all classes in the city.

This was mainly because the unique corner site meant there was a separate entrance for the riffraff in the cheap seats off Frederick Street.

With rumblings of another war on the horizon, Mr Milne also said the Kingsway would “have a beneficial effect on jaded nerves and tired bodies”.

Architect Leslie Rollo was complimented for his work on the vast Art Deco venue.

But unlike other state-of-the-art cinemas unveiled in the city in the 30s, he would not allow it to be referred to as a “typically modern” building.

His curious insistence was down to the fact he had read in a newspaper that Nazis were defending prison camps saying nothing was wrong with them; they were “typically modern buildings”.

The opening film was “A Man to Remember” starring Anne Shirley, but the curtain came down on the cinema in 1963.

The venue became the largest bingo hall in the north of Scotland and was a runaway success.

To this day it remains a popular bingo hall and the last of the city’s Art Deco cinemas to survive as an entertainment venue, born out of a decade bookended by despair and war.