A radical plan to create a pier, a lido and a new suspension bridge in Aberdeen were among suggestions drawn up as part of a vision for the city’s future during the Festival of Britain in 1951.

The national celebrations, which took place between May and September in 1951, were designed to provide a stimulus to the country following the austerity which followed the Second World War.

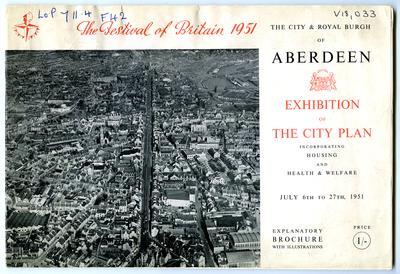

And the public were invited to attend an exhibition of a transformational city survey and plan, prepared for the Corporation of Aberdeen by W Dobson Chapman & Partners, a town planning consultancy.

The event, which also included exhibits by the housing and health and welfare departments, was held in the Music Hall from July 6 to 27.

Proposal would have increased cruise ship potential

It included a proposal to construct a pier and a lido at Aberdeen beach, along the lines of the structures in such places as Brighton and Blackpool, and was designed to boost tourism levels and capitalise on the city’s proximity to the North Sea, while seeking to increase the potential for cruise ships to visit the region and offer a boost to both Aberdeen and Aberdeenshire.

The plan also called for an extensive new council housing programme to tackle some of the worst urban deprivation in any British city.

Barney Crockett, the Lord Provost of Aberdeen, told the Press and Journal about the proposals and what had motivated them.

He said: “The Festival of Britain was a landmark event, a celebration of a future not yet delivered but overflowing with promise.

“Whilst the national focus was on the South Bank of the Thames, every part of the UK embraced the opportunity to take part, each with its own theme.

“It was no coincidence that Aberdeen chose planning as its theme. The people needed a better environment and especially better housing.

“Aberdeen was, by a long way, the poorest housed city in Great Britain. 60% of homes had no individual WC compared to 30% in the rest of Scotland.

“Amazingly, 5,000 homes had no washing facilities of any kind within the home, more than all other Scottish cities combined and 20 time more than in Glasgow. A quarter of homes were over crowded even by the standards of the time. No wonder the cry was for council housing.

“Experts were called in to assess the situation. A monumental report was produced, and the proposals were put on display at the Music Hall.

“As well as housing, leisure and tourism was not ignored in the city plan and there were extravagant proposals for the development of the beach area including a lido and a pier.

“In the event, much of the housing was built but many of the others plans were put on long term hold as the role of local government was reduced.”

Vast changes were envisaged in development plan

The Evening Express reported in July 1951: “When Lord Provost [William] Reid opened Aberdeen Corporation’s town planning, housing and health welfare exhibition in the Music Hall, he was giving a send-off to a feature that aims largely at providing an impression of the city of the future.

“Under the town development plan, vast changes are envisaged, but it will be well into next century before they finally materialise.

“By means of scale models, plans and pictures, the exhibition lays emphasis on the new housing estates and the plans for the redevelopment of the central areas. Scale models reveal the layout of the neighbourhood units that will eventually stretch out the city boundary – Kincorth, Kaimhill, Mastrick, Summerfield and Northfield.

“The Tullos industrial estate model is on view; so is the proposed lay-out of the beach with a new pier and lido; and of the suspension bridge that will eventually span the harbour navigation channel from Greyhope Road on the south side point near the Round House.

“It will be high enough to allow the free passage of all ships which are ever likely to use the port.”

What was the Festival of Britain?

It was an event which reverberated throughout Britain and highlighted a series of ambitious new visions for the future.

Visitors to London thronged to the South Bank and marvelled at a plethora of technological innovations, which were displayed on what had previously been a 27-acre bomb site surrounding Waterloo Station.

Inspired by the Great Exhibition of 1951, and devised by Labour politician Herbert Morrison, it was staged across the country throughout the summer 70 years ago, and promoted science, technology, industrial design, architecture, arts, culture and sport.

A large-scale programme of events was arranged in every part of the UK with the aim of serving up, as the organisers hoped: “a tonic for the nation”.

Most of the activity centred on London, which attracted millions of tourists from May to September, but there were extensive arts and cultural festivals in Perth in May, Inverness in June and Aberdeen in July, while HMS Campania, a Royal Navy aircraft carrier, was used as a floating exhibition hall and docked in Dundee and Glasgow.

The whole country got on board for the ride

Displays were organised on a grand scale in every major British city. Heavy engineering was the subject of an exhibition of industrial power in Glasgow.

The South Bank in London, which was the main centre of attention, featured ‘upstream’ and ‘downsteam’ pavilions with shows about everything from schools and health to homes and gardens and sport and cinema, and included an abundant array of restaurants, cafes, dairy bars and tea shops.

Linen technology and science in agriculture were documented in a “Farm and Factory” festival in Belfast. And a smaller sampler selection of the South Bank proceedings was staged on the Campania which travelled round the coast of Britain throughout the summer of 1951.

The public response was phenomenal.

Historian Kenneth Morgan described the event as a “triumphant success”, during which time “millions flocked to the South Bank site, to wander around the Dome of Discovery, gaze at the Skylon, and generally enjoy a festival of national celebration.

“Up and down the land, lesser festivals enlisted much civic and voluntary enthusiasm. A people curbed by years of total war and half-crushed by austerity and gloom, showed that it had not lost the capacity for enjoying itself. Above all, the festival made a spectacular setting as a showpiece for the inventiveness and genius of British scientists and technologists.”

This was a bold claim. But there were other reasons why the festival struck a chord with so many people and not least in Aberdeen.

Tackling horrific poverty in the Granite City

Just 70 years ago, the chronic poverty and slum life in the north-east’s biggest city was on such a massive scale that it compelled politicians, social planners and architects to work together to devise solutions.

A brochure, produced to tie in with the event, featured a striking photograph looking up Union Street from Holburn Junction to the Castlegate. The back cover highlighted a section of the city model with proposed designs for the same area, which had been created by J B Thorp of London.

Many of the suggestions were radical, such as the notion of constructing a new pier to cater for visitors to Aberdeen Beach and relocating Robert Gordon’s College to Marischal College, while demolishing large numbers of slum dwellings and replacing them with modern high-rise flats.

Some of the concepts were more practical than others, but there was no doubting the very real housing crisis which had to be tackled.

The festival went with a swing in Aberdeen

Even as officials were grappling with a variety of post-war social problems, many residents in Aberdeen were determined to accentuate more positive aspects of north-east culture during the Festival of Britain.

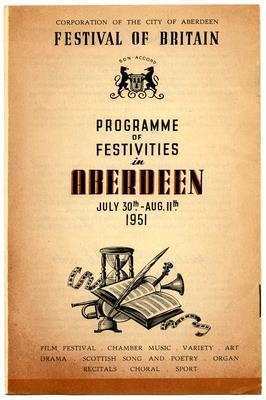

A colourful poster with a theatre-influenced design listed the programme of events which were held between July 29 and August 11.

The celebrations were organised by a wide number of groups, headlined by the Aberdeen Festival Society and the Corporation of Aberdeen in association with the Arts Council Scottish Committee.

Events comprised a church service, exhibitions of art and of crafts, theatre performances, concerts, and sporting competitions. The participants included the Arion Choir Ensemble, the Children’s Theatre and the Band of Royal Corps Signals who joined forces with local singers and instrumentalists.

The festivities took place at several venues around Aberdeen including Cowdray Hall, the Music Hall, King’s College Library, Gaumont Gallery and the News Cinema – and they were a major success with the public who had been starved of such mass entertainment for many years.

Isabel McLennan was among those who attended several of the performances and she recalled how they had lifted her mood and brought joy to the city.

The 82-year-old recalled: “My parents took me down to London on the train at the start of the school holidays and we were all amazed by the Skylon and the other technological innovations which were at the South Bank.

“It was the first time I had been out of Scotland, but we were made to feel very welcome when we walked into the exhibition area. It was packed with people and you could see how excited many of the visitors were.”

She continued: “When we returned to Aberdeen, we were looking forward to watching some of the shows at the festival in the city and there was something for everybody….there was a film festival, Scottish song and dance, drama shows and poetry competitions and sporting events and it was terrific.

“My dad said that it was like a gala day, only it lasted for the best part of a fortnight. Maybe we should have something like that again in Aberdeen after we have recovered from this pandemic?”

The Festival of Britain was a huge success

When the festival finished in September 1951, it was estimated that almost half the population of Britain had attended at least one of the events.

The guide book to the FoB described its legacy: “It will leave behind not just a record of what we have thought of ourselves in 1951 but, in a fair community, founded where once there was a slum, in an avenue of trees or in some work of art, a reminder of what we have done to write this single, adventurous year into our national and local history.”

The public certainly agreed. More than 75,000 people flocked to the various shows at the Aberdeen festival and 51,400 Dundonians boarded HMS Campania to examine some of the treasures on display.

The South Bank Exhibition attracted nearly 8.5million visitors, the majority of them British, but with 15% from the United States and large numbers from different parts of the Commonwealth, including Australia and Canada.

There was nothing on this scale again in Britain over a sustained period until the 2012 London Olympics.

A variety of festival reports can be watched via the British Pathe website.

Aberdeen reached the final of festival cup

Sport was also part of the programme and the Dons were involved in the Saint Mungo Cup, a one-off football tournament which was held in Glasgow.

The competition was contested by fourteen Scottish Division A clubs, together with Clyde and Queens Park from Division B, and the Dandies produced some excellent displays, defeating Rangers, St Mirren and Hibernian to reach the final, where they were beaten 3-2 by Celtic, despite taking a two-goal lead in front of a 81,000-strong crowd at Hampden.

The Glasgow Corporation, who had organised the tournament along with the Glasgow Football Association and provided the cup as their donation to the Festival of Britain, were left red-faced when the triumphant players and manager Jimmy McGrory examined the trophy and discovered that it was decorated with ornate life belts and mermaids.

It emerged it had been created in 1894 as a yachting prize, prior to being used again in 1912 for a competition between Provan Gas Works and a City of Glasgow Police team.

But, in every other regard, the festival was a triumph.