Charlie Chaplin is one of the most famous names in the history of show business.

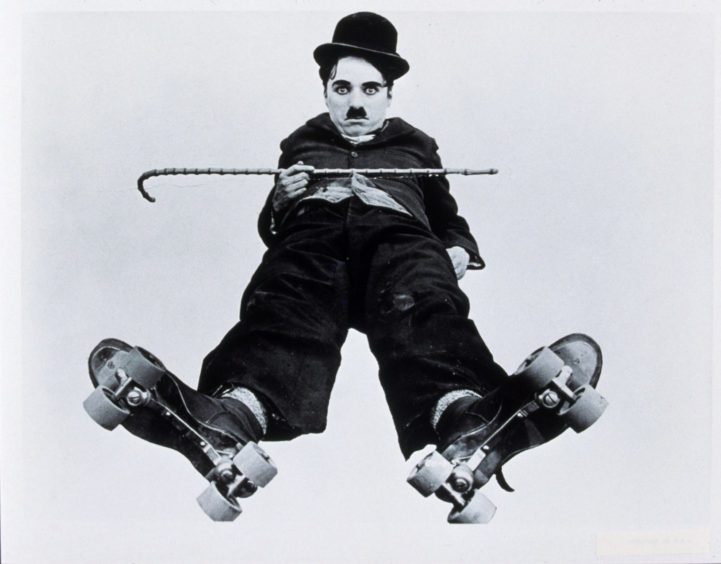

And there can hardly be a person alive who hasn’t seen an image of Chaplin, with his little moustache, downtrodden demeanour, and dogged determination to transcend life’s problems as a king of the road.

Yet, long before the Englishman moved to the United States, settled down in Hollywood and created the persona of The Tramp, who found love despite myriad travails, the young Chaplin was touring Britain and performing at venues in Aberdeen, Dundee, Glasgow, Edinburgh and other major cities.

Author A J Marriot, who has chronicled the early days of this comic pioneer and also delved into the history of Laurel & Hardy, has revealed how he was even involved in one of the earliest productions of a Sherlock Holmes play, which was staged while the detective’s Scottish creator, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, was still writing tales about the Baker Street sleuth.

And one of Chaplin’s visits – to the Tivoli Theatre in Aberdeen – was all the more poignant because he returned there almost 70 years later in what became a sensational exclusive for a north-east journalist.

Treading the Granite City boards

Mr Marriot, whose books were credited as inspiring the Bafta-winning film Stan & Ollie, directed by Peterhead-born Jon S Baird, has spent many years sorting out fact from fiction and his labours have provided an illuminating glimpse into the gruelling life experienced by the young Chaplin, as he journeyed the length and breadth of the country.

Born in April 1889 – in the same week as Adolf Hitler, whom he later famously caricatured in The Great Dictator – the youngster was a natural on stage and grew accustomed to travelling wherever he was allowed to tread the boards.

Mr Marriot said: “Although, for the first 21 years of his life, Chaplin remained based within the small area in South London where he was born, he made several appearances in Scotland, in various productions.

“The first batch came between 1899 and 1900, when he performed at theatres in Dundee, Aberdeen, Glasgow, and Edinburgh, as a member of the clog dancing troupe The Eight Lancashire Lads.

“It was four years before he returned, playing the part of Billy (the Page) in Sherlock Holmes, at theatres in Aberdeen, Dundee, Paisley, Dumfries, Kirkcaldy, Dunfermline, Perth, Motherwell and Greenock.

“Then came several appearances with the comedy sketch troupe Fred Karno’s Company of (London) Comedians, in which Chaplin formed the character which he then carried over into many of his films.

From football sketches to ‘mumming’ birds

“His earliest appearances with the Karno Company were in 1908 in The Football Match, which played in Edinburgh, Glasgow, and Dundee.

“Then, next up, he was in Mumming Birds at Aberdeen, Greenock, and Glasgow.

“Almost every theatre in the country lays claim to Charlie Chaplin having played there, but the vast majority of these can be dismissed as wishful thinking rather than a matter of fact.

“But I have recorded almost every single one of the thousands of stage appearances which Chaplin made throughout the UK, including the venues, the dates, and the sketches or plays in which he acted.”

Chaplin was revered, then reviled in America

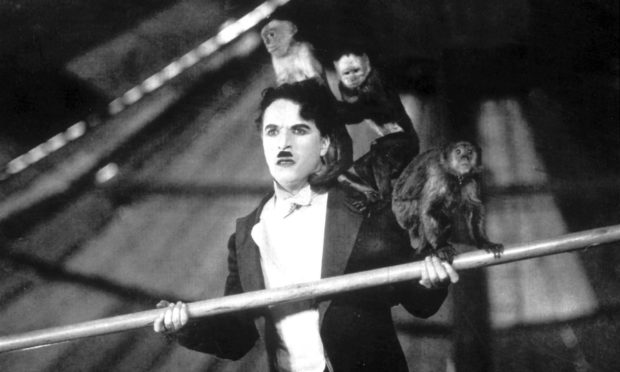

Chaplin’s prolific work rate, fertile imagination, acrobatic artistry and ability to bring a tear to a glass eye, made him one of Tinseltown’s most stellar figures, both during the silent film era and after the advent of talking pictures.

In his prime, he was feted for such works as The Kid and The Gold Rush and, spurning an immediate move to talkies, lavished care and a significant budget on two ambitious and highly-praised movies City Lights and Modern Times.

He helped bolster morale during the Second World War with his satire on Hitler – otherwise known as Adenoid Hynkel – and, even in his 60s, seemed destined to enjoy a lifelong love affair with Stateside audiences.

However, his reputation was battered and bruised in the febrile environment after the war when tensions grew between the US and the Soviet Union.

Chaplin was accused of having communist sympathies, and some members of the press and public found his involvement in a paternity suit, and marriages to much younger women, scandalous.

An FBI investigation was subsequently opened into his conduct in the aftermath of the McCarthy witch-hunt, with the rancour and recriminations forcing him to leave the United States and settle in exile in Switzerland.

And while, eventually, he was recognised by the American film industry with an honorary Academy Award for “the incalculable effect he has had in making motion pictures the art form of this century” in 1972, just five years before his death, it offered him no recompense for his treatment.

He was bitter and resentful of the persecution he had endured and refused to have anything to do with the media in his twilight years.

Or at least, that was the case until he visited Banchory for a holiday with his wife and locked horns with a resourceful wee loon from Maud

Tracking down a Hollywood screen legend

Jack Webster, a former feature writer with the Press and Journal, had grown used to interviewing some of the biggest names in sport and showbusiness.

He traded banter and fake blows with the great Muhammad Ali when the legendary boxer visited Glasgow in the mid-1960s. And he later produced such contrasting worlds as a biography of best-selling author Alistair MacLean and the official centenary history of his beloved Aberdeen FC.

However, Chaplin proved a far tougher nut to crack. Although Webster learned that the now-reclusive actor occasionally made very private visits to Scotland – a country which he loved – he had vowed “No more interviews” and lived up to that promise throughout the Sixties.

It seemed a forlorn hope that anybody would be capable of changing his mind, but then the information emerged in August 1970 that Chaplin had made a booking at the Tor-na-Coille Hotel in Banchory.

That led to Webster booking a room at the same venue, where he sat reading books and magazines in the foyer, day after day, hoping against hope for a glimpse of Chaplin’s limousine and a chance to approach the great man.

And finally, his patience was rewarded.

A foot in the door and the gem of an idea

As he recalled: “I watched the elderly Chaplin checking in with his much younger wife, Oona [the daughter of the renowned playwright Eugene O’Neill], but made no move until after dinner.

“When that was over, I now had to make my pitch. Because of his age, I made my approach to Oona, explaining that this was not a witch-hunt, but merely a desire to write about a childhood hero.

“She reminded me of his antipathy to journalists and, in any case, they were leaving after breakfast and there wouldn’t be much time. But she would ask him and bring his answer in the morning.

“So I was down in good time when she appeared with the news. And no, he would not be changing his mind.”

Getting a good sign helped open the door

Jack, though, was a determined fellow. Having purchased a copy of Chaplin’s autobiography, he decided to ask for the legend’s signature on the book – and followed that up by requesting a wee message for his three sons.

If the ice hadn’t melted by this stage, it had definitely thawed. “I handed him my notebook and was intrigued to see that he was not only signing his name, but drawing for each of my boys a sketch of himself – the bowler hat, the moustache, the baggy breeks and the cane.

“While he sketched, I took the opportunity to talk to him, dropping in the odd question and finding, to my surprise, that I was getting answers.”

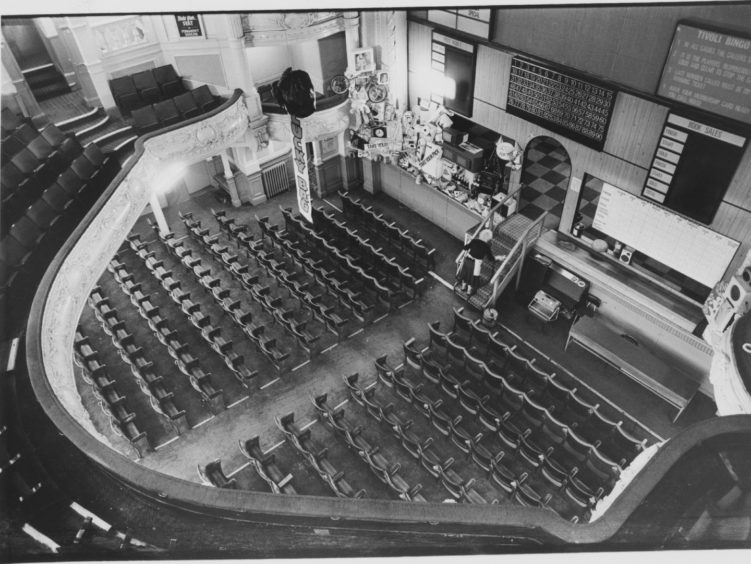

Then came the big breakthrough. “I reminded him that, in the early part of the century, he had appeared at the old Tivoli Theatre in Aberdeen. Yes, he remembered. He was an unknown teenager in the chorus of the troupe [as indeed was Stan Laurel]. And that lit the spark.”

One last trip to the old Tivoli

Webster, who died last year, could hardly believe what happened next. But it was a story which any journalist could have dined out on for decades.

In response to the question about the Tivoli, Chaplin replied: “That was before Stan and I went off to America.”

As Webster told him: “Well, the old Tivoli is still there.

“It’s now a bingo hall, but it looks exactly the same as when you left it all those years ago.

“How would you like to see it on your way through Aberdeen today?”

Chaplin said: “Yes, I’d like that. Just speak to the chauffeur.”

Jack said: “The first thing I did was to phone a photographer in Aberdeen. ‘Get down to the Tivoli, Ron, and I’ll be there in half an hour with Charlie Chaplin’.

“I wasn’t sure if he had fainted, but he was there when we arrived.

“On our way to the city, Charlie opened up. After all these years of avoiding the press, I think he sensed there was no harm in a chap like me.

“When we arrived at Guild Street on a fine summer day, there was nobody to be seen. But within a few minutes, word spread that Chaplin was here – and people began to arrive in droves.

“The crowd was still growing, to the point that we had to usher the frail old Charlie into his limousine. I shook his hand, thanked him, said goodbye and knew I had come as near as anyone to achieving that elusive interview.”

And, as Chaplin looked back at the Tivoli, he also waved his hand – as if recognising that he had returned to the roots of the sort of venue where his career had started so many years earlier.