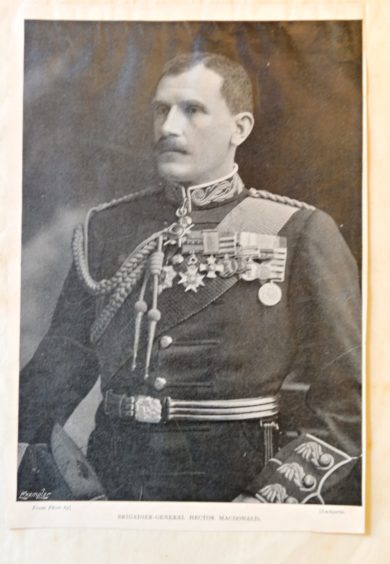

No Scottish private had ever risen to the exalted ranks of Major General in the British army.

None was more decorated for bravery and leadership in battle.

None was a Gaelic speaker from a humble Ross-shire croft, knighted and made an ADC to Queen Victoria.

And can any general boast two monuments to his memory on his home turf?

Yet Hector Macdonald, ‘Fighting Mac’, was to die tragically by his own hand aged just 50.

His popularity was such that people simply didn’t believe he was dead and there were various ‘sightings’ of him all over the world for years afterwards.

His funeral, intended to be small and private in Edinburgh, was attended by 30,000.

Days later, a lament was penned in his honour by James Scott Skinner.

Hector the Hero is still in the repertoire of every fiddler and piper.

They just don’t make them like Major General Hector Macdonald these days – so where did it all go wrong?

Humble origins

Born in West Rootfield farm, Mulbuie, in 1853, Hector’s background would have given him a certain grit.

The land around the farm had been the subject of clearances within living memory, with bitter tales of cruel evictions no doubt vivid in people’s minds.

Hector’s biographer Thomas Coate in 1900 says: “The poorly fed but industrious crofters tore a precarious subsistence from stony, hungry soil, reclaimed from what had been for centuries the tough rearing ground of whin and heather.”

The croft houses were higgledy-piggledy black houses, the implements primitive.

But Hector’s circumstances weren’t the worst.

Dingwall ceilidh maker, storyteller and author Ewan McVicar has researched Hector’s early days.

He said: “His father had come to Rootfield from Kilmorack, three miles south west of Beauly. He was a travelling ‘dry-dyker’, a builder of rough stone dykes and walls of houses.

“On his travels in Stratherrick he met Ann Boyd, descended from the Ayrshire Boyds who were earls of Kilmarnock.

“Ann was a strapping comely lass. Shortly after, the two were married.”

A ‘hardie stirkie’

Hector was the youngest of five sons, described as a ‘’hardie stirkie’, already showing signs of things to come as a vigorous leader in boy’s battles.

He was neither tall nor small, but broad, strong, sturdy and tough.

He helped his father round the croft and earned money for the household as a herder before entering into the employment of a Mr Robertson, a junior Baillie in Dingwall.

He was willing and painstaking, Hector’s biographer Thomas Coates writes, but, strangely for a soldier who was to depend on horses during battle, his employer found him ‘an awful bad horseman, and many a good thumping I gave him for one of his cantrips in the saddle.’

“Once Robertson returned unexpectedly and discovered Hector galloping around one of the fields on a pony with a fork for a sword, imitating his master and giving out orders in a stentorian voice, to an imaginary regiment.

“The sudden appearance of Mr Robertson so upset the aspiring field officer that he fell off the pony’s back.”

Aged 15, Hector was apprenticed to a Dingwall draper and went to work at the Clan Tartan and Tweed House in Inverness.

Hector’s military career begins

This wasn’t much to the taste of the soldier within Hector, as a couple of years later he joined the Inverness-shire Highland Rifle Volunteers and, lying about his age, he deserted his five-year apprenticeship aged 17 and went on to enlist with the 92nd regiment, the Gordon Highlanders.

After training in Aberdeen’s Castlehill Barracks, Hector’s military career was under way.

He rose rapidly through the non-commissioned ranks to become a Colour Sergeant by 1880.

Ewan relates in his booklet, Hector The Hero of the North, that he was sent to soldier in India and “for eight years played his part in the labour and ceremony of the Raj.”

Ewan recalls one of Hector’s own stories of the time: “The commanding officer called for me and said: “Corporal Macdonald, I have no fault to find with you and I am going to promote you to the rank of sergeant.

“Remember this, that a sergeant in the 92nd Highlands is equal to a Member of Parliament in the United Kingdom.”

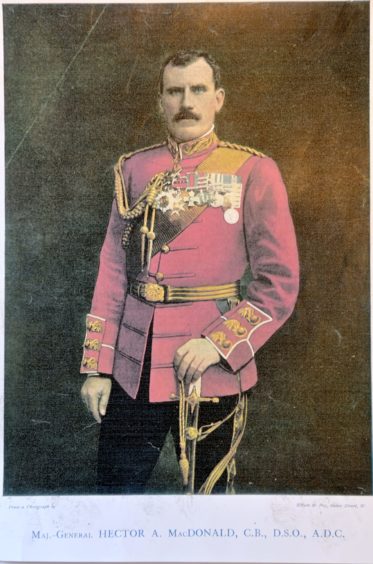

His rise through the ranks was meteoric and Hector went on to distinguish himself in battle in campaigns in Afghanistan, South Africa, Sudan and Egypt earning 10 decorations, 14 clasps, mentioned 11 times in dispatches and thanked by both Houses of Parliament.

He served as a subaltern in the Boer War of 1880-81 and though he was taken prisoner, he fought so bravely the Boers gave him back his sword.

Saving the day in the battle of Omdurman

The pinnacle of his career came in the battle of Omdurman (now a suburb of Khartoum in central Sudan) under Lord Kitchener.

Ewan writes that Kitchener had thought the battle won, and turned his attention away from the field.

“Hector saved the day. His men were charged by a previously unseen mass of dervishes, and Hector manoeuvred his well-drilled troops so remarkably that he became the media hero ‘Fighting Mac.’

“When the fight was over Macdonald’s troops had an average of only two rounds left per man.”

On a lap of honour around Scotland after Omdurman, Hector returned briefly to his homeland, visiting Inverness, Dingwall, Tain and Invergordon where civic holidays were declared.

Ewan says: “In Tain and Invergordon Macdonald was given a guard of honour by the local volunteers and in Invergordon his carriage was drawn along the High Street by local men.

“Bands played ‘See the Conquering Hero Comes.’

“In Tain his Highland roots were celebrated with a banner in Gaelic reading welcome to our Highland hero and he was presented with an address in the form of an illuminated star, which included pictures of Inverness, Tain, Omdurman, Majuba Hill and Kandahar.”

Hector continued to cover himself in glory commanding the Highland Brigade on various fronts in the Boer War of 1899-1902.

He was knighted in 1901 and appointed Aide-de-Camp to Queen Victoria.

But in 1902 things began to go wrong.

Accusations of homosexuality

Hector had been sent to command British troops in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka).

Ewan explains: “There he was accused of homosexual behaviour with local boys, an offence punishable by military law.

“He returned to the UK, then was advised to clear his name through a court martial, but on the way, in a Paris hotel, he read a sensational account of the accusations in the Paris edition of The New York Herald, and Hector shot himself.”

He was 50.

Some historians believe the charges against him may have been trumped-up by his influential enemies.

Rumours had been circulating by jealous colonial officials after Maj Gen Macdonald was posted to Ceylon.

They felt they should not have to answer to a man they claimed to be of “low breeding”.

Liberal MP for Ross and Cromarty, James Galloway Weir, said two years later that Sir Hector had been ‘driven to his doom by a society clique.’

The crofter’s son, always an outsider among the public school educated elite of the army, could have been the victim of a conspiracy to destroy him – but others say there were concerns about his promiscuous behaviour before Ceylon.

The Highlands had produced generals before Hector, but they were the sons of lairds and chiefs, essentially aristocracy.

It was little known at the time, but Hector had been married for 20 years and had a son. He had seen them only four times during his long years soldiering.

He had met 15-year old Christina McDonald Duncan while walking along the Water of Leith in Edinburgh in 1883, when he was 30.

They were married the next year in her parents’ house in Murrayfield.

After his death, instead of a funeral with military pomp and circumstance befitting his stature, Fighting Mac was reclaimed by Christina and buried in Dean cemetery in Edinburgh.

The funeral was supposed to be in secret, but 30,000 people lined the streets and more than three times that number filed past his grave in the following days.

Memorial plans got under way locally

Shortly after his death, a committee headed by the Duke of Argyll began to seek support for the construction of a fitting memorial on Mitchell Hill overlooking Dingwall.

This was designed by Glasgow architect James S Kay, a square tower in the Scottish Baronial style, 100ft tall, erected in 1907.

Ewan writes: “In September 1905, the foundation stone was laid.

“Beneath the stone was placed an iron box containing a biography of Hector, list of town councillors and burgh and county officials, copies of newspapers, a list of the Memorial Committee and officials and coins of the realm.

“What a lot of names being honoured by association.”

Constructing the monument wasn’t plain sailing.

The builder, Mr MacKenzie of Tain, constructed a light railway, using steam, to take the materials up the hill, prompting complaints by residents of a water shortage in their own supply.

Thousands turned out for the opening on May 4 1907, by the Marquis of Tullibardine.

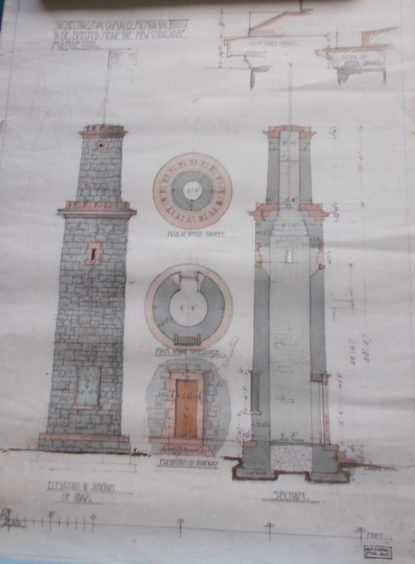

Plans to honour him in Mulbuie

Meanwhile in Mulbuie, a young architect, John Duncan Forbes, living not far from West Rootfield drew up designs for a memorial in Hector’s township.

They were exhibited in the window of Mr Uqhuart, a Dingwall tobacconist, and described as in the form of an ancient Scottish round tower, not of pretentious character, but still worthy of the district.

By 1906 the money for it had been raised by subscription, with the bulk of the funds coming from the poor people in the district.

Fundraising efforts included a packed concert in nearby Mulbuie school.

But curiously, much less has been recorded about this monument, Ewan notes.

“It’s not mentioned in the Buildings of Scotland, Highlands and Islands, by John Gifford and there is no mention of it in the Mulbuie school log book or the Ross & Cromarty county minutes of the time.

“It feels almost like a conspiracy of silence.”

Footnote – Hector the Camp Coffee soldier?

When the inventors of Camp Coffee decided they needed a new image for their brand they decided a Highlander in full regalia would fit the bill.

It’s said to be Sir Hector Macdonald on the label, originally being served Camp Coffee by a servant, with a more modern version showing the servant and Sir Hector enjoying a cup of coffee together.

An earlier version of this story wrongly suggested that the Victoria Cross was among the major general’s many decorations. Thanks to the readers who pointed out this error which we are pleased to have corrected.