Calls to reopen the Formartine and Buchan Railway, one of the lines lost to Dr Beeching’s cuts have been gaining momentum in recent months.

The first section of the Formartine and Buchan Railway opened on Thursday July 18 1861 with a route between Dyce and Mintlaw.

The railway rushed through the Formartine countryside past yellow broom and heather-clad hills.

It wound around “well-nigh mansions” and through wilderness where only “sturdy farmers” could penetrate the tough land.

It was farmers that pushed for the line to be built to help transport livestock to market.

The line didn’t follow the most picturesque route, nor did it follow the most practical one for engineering.

Instead, it zig-zagged through the countryside, dictated by landowners and investors who either wanted the railway close to their homes – or not.

The following year, a 13-mile extension was added from Maud to Peterhead, and in 1865, the 29-mile branch to Fraserburgh opened.

The railway survived economic ups and down, two world wars and the advent of the motorcar, but it couldn’t dodge the swingeing cuts of Dr Beeching.

Dr Beeching’s reports of 1963 identified 5,000km of track and 55% of stations which he recommended to be closed to make the railways more efficient.

The loss of the Formartine and Buchan line is regarded as a short-sighted decision that isolated already rural communities, and one that many want reversed.

Join us as we hark back to the hazy days of steam on a whistle-stop tour through Formartine and Buchan from Dyce to Fraserburgh.

Dyce

When Dyce Station opened in 1861, it had four platforms – two for the Great North of Scotland Railway (GNSR) and two for the Formartine and Buchan Railway.

A busy commuter station these days, it’s hard to imagine that it closed in 1968 as part of Beeching’s cuts with one of the GNSR lines also removed.

The station reopened in 1984, and in 2019, the track was redoubled to Inverurie.

Dyce had an impressive signal box at the south end of the platform, which, until it was demolished in 2019, was the last surviving GNSR example.

Parkhill

Approaching Parkhill Station, the first passengers of 1861 enjoyed views over Parkill House and its policies to the right.

The quaint and quiet station was not regularly used, and the most excitement there in years was the mystery of why the station clock stopped in 1911.

The riddle was solved by a clockmaker who discovered that a 10ft shoot from a rose tree on the platform had crept its way into the clock.

The lack of passenger traffic didn’t go unnoticed – when British Rail carried out a survey in 1949 and found only 34 passengers used it that year, the station closed in 1950.

Newmachar

Upon leaving Newmachar, the railway entered one of the deepest cuttings on the line.

Intense and heavy labour was needed to split the rock to allow the track to climb into the open country beyond.

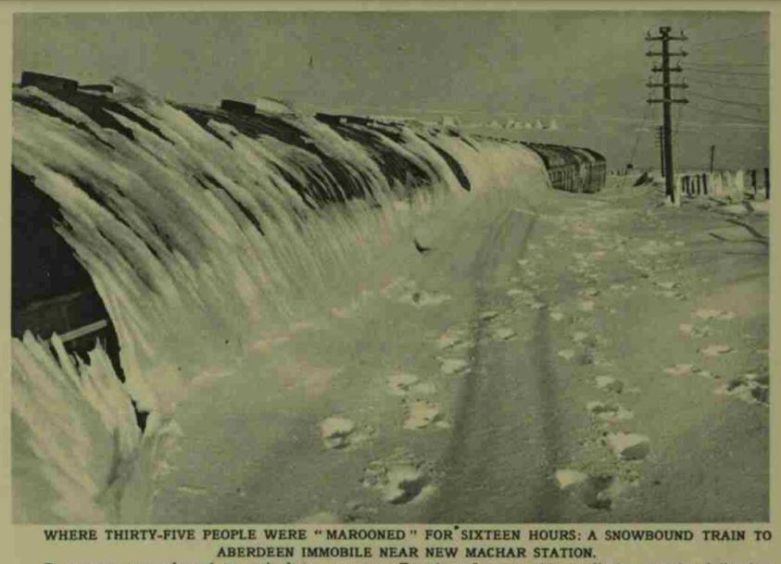

The deep cuttings – particularly one to the north nicknamed ‘Satan’s Den’ – meant the line often became blocked with snow in the winter.

One incident in January 1960 saw 57 passengers trapped in a stranded train for 16 hours near Newmachar Station.

The train was engulfed in snow after a blizzard swept across Aberdeenshire, blocking the four main rail lines.

The station, which also had north and south signal boxes, closed in 1965 and was turned into a family home.

Udny

Arriving at Udny, the new station was described as a “blooming rose surrounded by thorns”, the travel writer was not impressed with the surrounding wasteland.

However, he did add that “the appearance at the station is made up for by the smiling country around”.

Perhaps more industrial than some of the other quaint stops along the line, Udny had two platforms, a station building, goods yard and signal boxes, as well as a large passing loop.

The station saw its last passenger use in 1965, the signal boxes limped on for another year, before the entire line closed in 1979.

Homes now stand on the sidings, but relics of the railway including old level crossing gates have survived.

Logierieve

The approach to Logierieve was a more pleasing sight for the passenger, with the little mansion house hanging “lovingly on the banks of the line”.

There was a single platform and upon it stood a pretty little station cottage surrounded by trees.

The picture-perfect stop was the scene of high drama in 1894 when a traction engine crashed through a nearby bridge crossing the railway, blocking the track.

A hefty vehicle, station staff had to think quickly to keep the network running – especially as the morning mail train was waiting to get through.

It was several hours before the traction engine could be raised, so passengers heading north and south transferred onto other trains at either side of the blockage.

The engines pushed their carriages until Ellon and Udny respectively, where turning loops meant the train could be put back in front.

The charming Logierieve station closed in 1965, but was converted into a home where walkers are now the only passersby.

Esslemont

The approach to Esslemont took passengers through “luxuriant fields” and local industry.

The train passed a busy brickworks, while the surrounding fields were heavy with crops, and the countryside dotted with crofts and farms.

The station was about a kilometre south of Esslemont, initially a single-platform stop with a cottage-like building, another platform was added in 1919.

When Captain Wolrige Gordon of nearby Esslemont Estate married Lady Florence Hay in 1895, the station was like a scene from The Railway Children.

To mark the occasion, flags and emblems were draped over the station and other buildings in Esslemont.

Esslemont Station was taken out of service in 1952, decades ahead of the line closing in 1979, and is now a home.

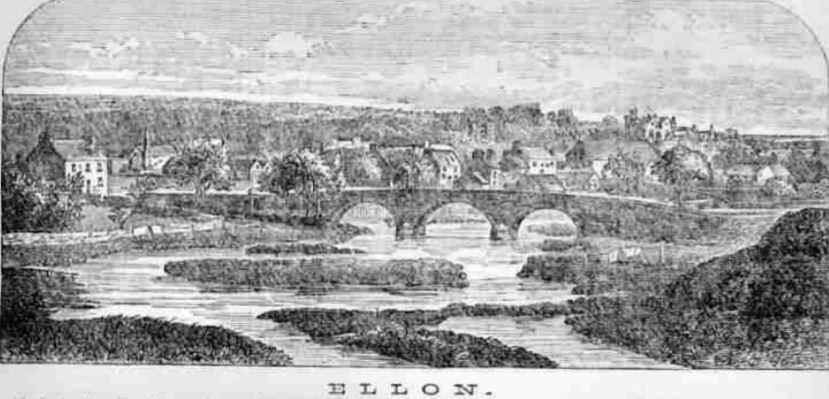

Ellon

When the railway opened, one highlight passengers were told to look out for was “the view of the little town of Ellon from the line, after you leave the cutting, it is one of the best that can be had of it”.

The idyllic part of the journey described “a bonny afternoon, with the sun glinting on pretty houses”, with the River Ythan “rolling and lolling, leisurely around the town”.

While the “proud tower of the magnificent Ellon Castle high over the town” could be seen from arriving trains.

Trains steamed into town across the picture-postcard style arched viaduct over the Ythan – like a scene on an old railway poster.

In town, Ellon Station was a busy one.

It was a junction stop with a branch line to Boddam as well as connections to Fraserburgh and Peterhead.

In its heyday there were three platforms and a large goods yard, and in 1896 the station was refurbished to accommodate a new waiting room and verandah on the central island.

Rails criss-crossed each other under the watchful eye of the signalman in the signal box, all overlooked by the nearby Station Hotel.

The branch line was the first to go, it shut in 1932, before the track was removed in the 1950s.

And by 1965, despite servicing a busy town, Ellon Station closed to all passenger traffic, the last train tooted its final whistle on October 2.

In 1973, a bid to reinstate a passenger service at Ellon and Dyce stations – and run a link from the city – was turned down by British Rail, before the line closed entirely in 1979.

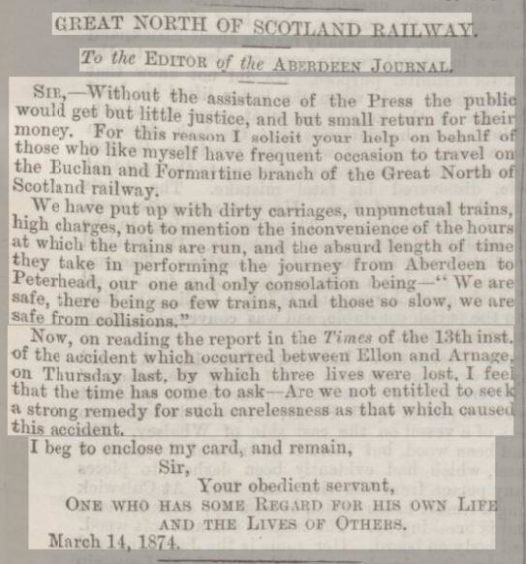

Arnage

Located near Arnage Castle, the station was another sleepy, rural stop with two platforms and a single-storey station.

Although the hustle and bustle was left behind in Ellon, Arnage had its fair share of incidents.

In 1874, a fatal collision occurred at Arnage when the 13.20 service from Aberdeen crashed into a light engine coming from the opposite direction – on the same line.

Two drivers and a fireman were sadly killed, and the story made headlines across the country.

The experienced driver of the bigger engine was “a strict tee-totaller” with years of “steady service”, and poor communication was blamed for the tragedy.

The Arnage accident resulted in calls for station masters to become responsible for giving signals to engine drivers to stop at stations where they were due to meet other trains.

Until then, drivers referred to a timetable which had thicker lines across columns showing where they crossed other trains.

Like the rest of the line, Arnage Station was taken out of service in 1965, but lives on as a home.

Auchangatt

Auchnagatt Station, or “The Gatt” as it was known locally, opened in 1861, and had a goods yard and loop.

Although not much was said about the station when it opened, a guide to the new railway did say that “a good inn stands opposite”.

And on local Auchnagatt holidays, passengers from the village were treated to cheaper fares to Aberdeen and Peterhead for days out.

Brucklay and Maud

It was predicted that the advent of the railway would turn the agricultural area of Brucklay into a thriving place.

When the station opened in 1861, it had two platforms, and when the Fraserburgh extension opened, another two were added.

The prediction had been right – it was a busy station, and its name was changed to New Maud Junction in 1865 when the additional branch line was brought into operation.

A report upon the opening of New Maud Junction declared: “This will now be an important station – in fact, next to the termini, it may be considered the most important.”

A network of tracks and sidings allowed trains from Aberdeen to be split or combined here, and proceed to Fraserburgh or Peterhead.

Latterly known as Maud, the station’s signal box was still in use up until 1969, four years after the station itself had closed, and the goods yard was used into the 1970s.

In recent years, the station has been given a new lease of life as the Maud Railway Museum, which tells the story of the busy station and its role in the Formartine and Buchan Railway.

The rebranding of Maud was not the end of the line for Brucklay, it reopened in 1865 as a new station further up the Fraserburgh line.

The second Brucklay Station was located for its proximity to now-ruined grand stately home Brucklay Castle.

A passing loop was added in 1891 and remained in use until the late 1950s, just a few years before passenger services were withdrawn.

The old station had been lying empty for 15 years when it was brought back from the brink.

In the mid-1980s, the building was lovingly restored by couple Leslie and June Henderson who turned it into a home.

Strichen

From Brucklay, the railway took passengers over a fine viaduct and into the “picturesque village of Strichen”, on the banks of the River Ugie.

A railway agent described the approach: “The station houses are extensive and commodious; and for the benefit of those who look to creature comforts in travelling, there are several good inns.”

The two-platform stop lasted for 100 years before it closed in 1965, although it was a popular stop for rail tours in the 1970s before the line was lifted.

The old station is now a home, but still bears the name and station clock on the platform side of the building.

Mormond

Steam trains struggled and strained against the steep gradient of Mormond Hill on the approach north.

Nearby residents joked that as the train got slower and slower, and the smoke got thicker and thicker, the engine could be heard saying “will-I-manage… will-I-manage”, “I-think-I-will, I-think-I-will” and then reaching the summit “I-kent-I-wid, I-kent-I-wid!”

Mormond Halt, began life as Mormond Station in 1870 before the London and North Eastern Railway renamed it Mormond Halt in 1939.

The station building is unique in that the stationmaster’s house was built over the waiting room – to get inside he had to go around the back and climb a steep stone staircase.

It once had a prize-winning garden with “Mormond” spelled out in white stones, but it has long been reclaimed by nature.

The writing was on the wall for Mormond even before Dr Beeching swung the axe.

In 1950, it was announced the stop was to be added to British Railways’ “stations to close” list as only a handful of passengers used the four services a day that passed through.

It clung on until October 1965 when the line closed to regular passenger traffic.

Lonmay

After conquering Mormond, trains were well on their way to the Buchan coast, stopping first at Lonmay.

It was a two-platform station with a passing loop and goods yard – a busy one that services packed with fish from Fraserburgh would pass through.

The station faced the same fate as the rest along the line during railway closures, but unlike the others, the building did not survive after closing in 1965.

Rathen

Leaving Lonmay, steam trains meandered through “fine country” with splendid views of the mansion houses of Craigellie and Cairness on the approach to Rathen.

Another single-platform station, Rathen also had a goods yard and signal box.

During particularly poor winter weather, the deep cuttings between fields around Rathen meant trains often got stuck in snowdrifts several feet deep.

The station became ruinous after closing in 1965, but was brought back into use as a home many years later.

Philorth

On the approach to Fraserburgh, the line crossed an avenue leading from Cairnbulg Road to Lord Saltoun’s country mansion, Philorth House.

For the deep inconvenience, the lord – who had a £6,000 stake in the railway company – demanded a station, fully signalled and operated at the expense of the railway, on the basis that only he and his heirs could use it.

He also demanded that he could stop any train by request and have free use of the railway “to pursue and apprehend poachers”.

Incredibly, the railway obliged and the private Philorth Station opened in August 1865 and remained for family use only until 1926.

When it opened, it was said to be “the neatest and best finished” on the line extension to Fraserburgh.

In 1926, the station became Philorth Halt and remained in use until its centenary year, 1965.

Fraserburgh

After two hours of travel from Dyce, weary passengers would find themselves at Fraserburgh, the end of the line.

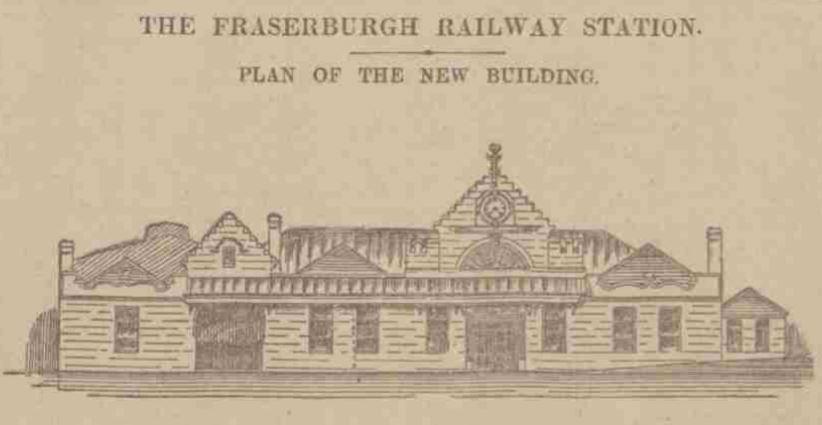

The original, small station opened in 1865, but was replaced in 1903 with a bigger granite building more befitting of the Broch.

As well as acting as a terminus for the Formartine and Buchan Railway, Fraserburgh needed a bigger station to accommodate the opening of the St Combs Light Railway.

The new station was to be “thoroughly up-to-date, with provision made to meet every modern requirement in the way of convenience and comfort”.

But the station was run down after the war, and in 1953 a Press and Journal reporter raised concerns about the state of the building.

He wrote: “Nothing appears to have been done to reconstruct this station. Great gaping holes in the roof and walls leave a skeleton of ironwork.

“The walls of the waiting room were covered with intimate little stories of the teenage loves of the Buchan district.

“‘Eliza loves James’, there it is for the whole world to see in dirty red paint.”

The station building and platforms were removed in the 1980s after the line closed in 1979.

The rails themselves were lifted and stored at Fraserburgh Station before being shipped to the EU and sold for scrap.

But the locomotive shed still stands, a lingering totem to a line that brought the city, country and coast together.