Not everyone who comes to the Scottish Highlands and islands and falls instantly in love with them has quite the same passion as one young Victorian woman.

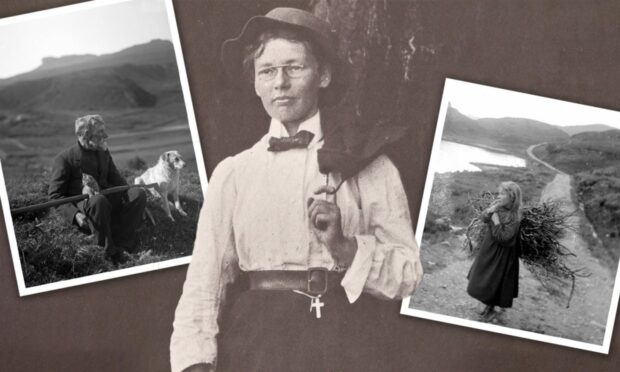

Mary Ethel Muir Donaldson was completely smitten upon visiting the Highlands from London at the turn of last century and went on to become an unconventional ethnographer, author of seven books and prolific photographer of a long gone era.

She’s all but forgotten now, but a tangible remnant of her legacy can still be seen in Ardnamurchan at what remains of Sanna Bheag house, the home she built for herself and life partner Isabel Bonus.

Otherwise, she is vivid only in the memories of a generation fast disappearing, and in her extraordinary collection of photographs taken between 1900 and 1930.

These are held in the Inverness Museum and Art Gallery and National Museum of Scotland collections.

Mary was born in Lambeth, London on May 19, 1876.

An early indication of her distinct personality was that she dismissed her given names, Mary Ethel Muir, preferring to be known as MEM, or MEMD.

When her godson Walter dubbed her Uncle Tonal, she was well pleased, and that name also stuck.

In the Highlands and islands, she was generally referred to as ‘Herself’.

It’s unclear what funded her independence and her travels, although members of Robin Erskine Waddell’s family, who were friends with the Donaldsons, believed it could have come from her father’s directorship of the Donaldson Shipping Line.

“Although I can find no evidence for it,” Robin says on his site ornaverum.org.

It seems MEMD was brought up by nannies and never went to school.

This didn’t stop her writing, or her scientific work studying chemistry and optics, allowing her to process her own glass negatives, prints and enlargements.

MEMD became a connection of the Waddells through her long friendship with his grandmother Hannah Findlay, and Robin remembers her visiting the family home.

“On the occasion of that visit to my parents’ house when I was about 8, she presented me with a picture-book of English Kings and Queens but I was horrified to see that she’d scribbled ‘Regicide’ in orange crayon across the portrait of Oliver Cromwell – I’d always been told it was very naughty to scribble in books.

“At some point in my early teenage years (perhaps after MEMD’s death in 1958), I was given a couple of thick quarto-sized ruled sketchbooks, containing a great many meticulous pencil drawings by Isabel Bonus, mainly of church architectural details and, I think, mediaeval or perhaps pre-Raphaelite women’s dress .

“As his godmother, she might have been expected to leave a substantial sum to my father Walter, though I don’t think she did.”

Unconventional and eccentric

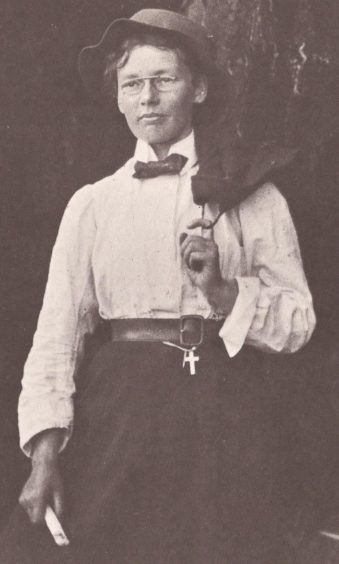

Her unconventional dress and eccentricity prompted Robin’s family to be ‘a little irreverent about her’, he admits.

He recalls a phone conversation with his aunt Jane Waddell Renaud, from which the following details emerged.

“Uncle Tonal was what Walter called MEMD when he was little.

“She enjoyed the joke.

“She always wore pork pie hats, stiff collars, wore her hair short and looked like a little man… She wasn’t entirely popular.

“She wanted to improve the local people’s lives [in Ardnamurchan] by building a road, I think to Fort William, but the locals strenuously objected.

“They thought, rightly, that it would ruin their way of life.

“She couldn’t see that.”

Collection of photographs taken by Mary Ethel Muir Donaldson

Aunt Jane also recalled that Compton Mackenzie may well have poked fun at her in his book, Hunting the Fairies.

Robin adds that having had no education MEMD’s writing style was dreadful, prompting her publisher to plead with her to have her manuscripts edited- to no avail.

As a Donaldson, she felt herself to be a proud member of the Clan Macdonald, as she records in her book Wanderings in the Western Highlands and Islands, when she enters ‘the land of Prince Charlie’.

“If is good to be a clanswoman, it is better to be entering upon your own clan territory, for the then, however landless you may be in reality, you feel fastening upon you a pride of possession such as is unknown to the pedigree-less proprietor who is landed only by purchase.”

Connection with crime writer

Author Jennifer Morag Henderson first came across MEMD when she was researching her biography of Inverness crime writer Josephine Tey.

She became so intrigued that she did further research and now gives talks about MEMD.

She said: “I discovered that she and Tey had written to each other.

“This was fairly unusual for Tey, as she didn’t often discuss her writing with anyone. MEMD had initiated the contact when she wrote to Tey with some comments and queries about one of her books, and Tey had then read MEMD’s latest book, which she thoroughly enjoyed.

“MEMD’s writing perhaps feels rather dated to a modern reader, but she had strong opinions and was not afraid to share them, and this obviously appealed to Tey – a woman with strong opinions of her own.”

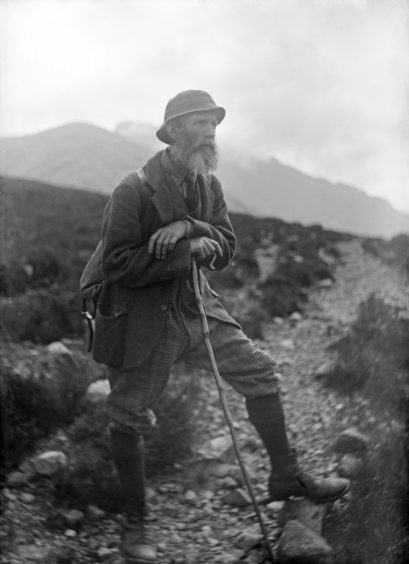

Jennifer also found out more about the subject of one of MEMD’s most enchanting photographs, Girl with Firewood.

She said: “The girl in the photo was called Christina MacVarish, and she was 12 when the photograph was taken in 1910.

“She lived with her four older brothers near Loch Morar.

“Her father drowned at sea when she was a baby.

“When she grew up, she married a gamekeeper, and they had nine children.

“However, one child died from leukaemia, aged only seven, and her husband had been badly wounded at the Somme and never fully recovered.

“Christina was widowed in her 40s. She lived until the 1980s, however, and became a proud grandmother to 23.”

Jennifer acknowledges Tales of the Morar Highlands by Alastair Roberts for part of this story.

Brush with the law

MEMD wasn’t afraid to brush up against the law.

The headline in the Oban Times of Friday August 3 1934 shouts “Authoress In Court In Oban- Motor Car Charges”.

She had allowed one of her employees to use her car without third party insurance; she had employed him as a driver without him holding a driving license; she lied on a application for a driving license for another employee, saying he was over 17, and she permitted him to use the car without insurance.

Police evidence was presented in court, including an account of how when questioned by police, MEMD “appeared to resent his questions and got very nasty.”

Fortunately from MEMD, Sheriff Chalmers held that she was the victim of misrepresentation by one of the employees and admonished her, with a fine of 10 shillings.

Sanna Beag

MEMD made her presence most vividly felt in Ardnamurchan.

She clearly took to the peninsula with a passion, to the extent that she built a home there, Sanna Bheag.

MEMD chose a spot with stunning views over Eigg and Rum for her home.

Sanna Beag was a large single-storey stone building in a rough T-shape, roofed with heather, built in around 1925/26.

She used local crofters and stonemasons from Tobermory in the constructions, and played her part in thatching the roof.

In vernacular style, they knocked the bottoms out of zinc buckets for chimney tops.

The house had its own hydro-generated electricity- it’s thought her brother John Muir Donaldson, a respected engineer, might have had a hand in this.

It was consecrated by the Rt Rev Bishop MacKenzie of Argyll and the Isles in what was the first Episcopalian service in the district for more than 200 years.

Tragedy strikes

Tragically MEMD’s home only had a life of around 20 years, burning down in 1947.

This prompted her to move to Edinburgh, where she died in 1958.

Isabel had died in a nursing home in 1941, possibly due to acute peritonitis.

Robin said the report was that medical attention was seriously delayed because of the continued lack of a well-metalled road between Ardnamurchan and the world outside.

The two are buried together in Oban.

MEMD wrote much on the Episcopalian faith, and left a considerable legacy to the Episcopal Cathedral of St Mary in Palmerston Place, Edinburgh for its refurbishment, further adornment of the chapel of All-Souls and its rededication to King Charles I and All Souls, according to Robin Erskine Waddell’s researches.

MEMD is remembered only for her religious work on their gravestone:

‘Here also lie the mortal remains of M.E.M Donaldson, her [Isabel’s] beloved friend who wrote books in defence of Scotland’s faithful remnant, the Scottish Episcopal Church. Departed this life on 17th Jan. 1958’

MEMD’s works include The Isles of Flame (1913), Tonal Mactonal (1919), Wanderings in the Western Highlands and Islands (1923), Islemen of Bride (1922), and Further Wanderings: Mainly in Argyll (1926), Scotland’s Suppressed History (1935), Till Scotland melts in Flame: Talks on Scottish Church history for young people, etc (1949). Many of these were illustrated by Isabel.