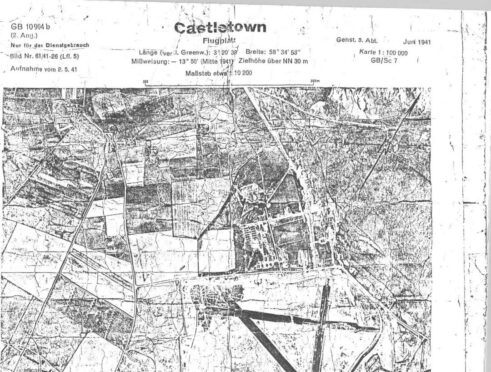

It’s hard to overstate the strategic importance of the far north of Scotland during the last war.

Because of its proximity to Scapa Flow, Britain’s most important naval anchorage, it was inevitable that the northern mainland would be within the enemy’s sights.

The government could forsee how Occupied Caithness would trap Britain into a pincer between Occupied France and Norway.

And if the Germans could control this section of the North Sea, it would spell disaster for the Allies’ transatlantic lines.

All to aware of danger

As war approached, Caithness residents were all too aware they were right on the frontline, and pretty defenseless.

The local rumour mill must have gone into overdrive in the village of Castletown in the summer of 1939 when two officials were spotted surveying the Upper Quarries area.

In late September, a stone crusher and tar plant were installed at the Upper Quarries, and machinery and men arrived on the farm of Thrudistoft.

An aerodrome quickly started to take shape, and would become RAF Castletown.

The base’s history has been documented in a booklet ‘Castletown Recalls 1939-1945’ produced by knowledgeable local people for Castletown Heritage Society.

In it John Swanson recalls: “ Excavations of runways were completed and approximately forty to fifty lorries were parked around the quarry.

“The carting of hard-core to Thurdistoft for bottoming went on day and night for many months. In due course the required amount of crushed stone had been delivered to Thurdistoft and stage two then started.

“The tar plant got going and the transporting of tar was again a round the clock effort.

“There were many drivers from outwith the county and they were all accommodated in and around the village of Castletown.”

To make way, people had to be displaced, homes bulldozed.

Construction begins

Construction began in 1940, and the base opened in basic form just as the evacuation of Dunkirk was beginning, and Norway was falling to the Germans.

A single officer and 10 airmen from 504 Squadron moved in before things were quite ready- the landing strip wasn’t finished so the first couple of planes in ended up hurtling down a slope, damaging their undercarriages.

The pilots heroically grabbed the wings of the rest of the incoming planes to try and slow them down.

By June 7 more personnel, stores and equipment had rumbled in and RAF Castletown became an operational fighter station of No 13 Group Fighter Command.

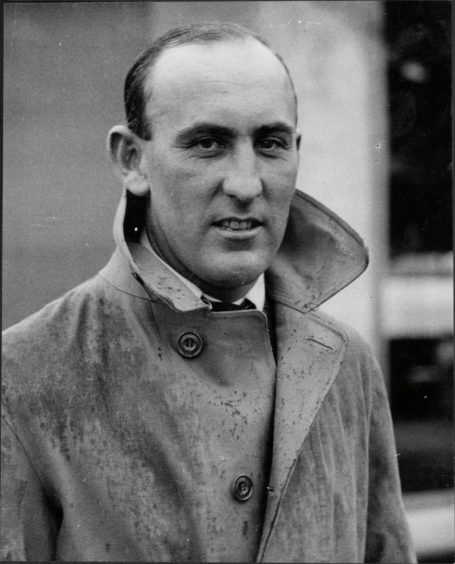

Local historian Drew Gutteridge discovered that the base’s first commander, David Atcherly, was a bit of a character.

“David, then a young man of 36, and his twin brother Richard were already well

known and respected figures within the service.

“Both brothers were highly individual and somewhat unorthodox characters. While David was in Castletown, Richard was commanding RAF Drem near Edinburgh, and a keen sense of competition developed between them regarding station defence.

“David won the day when he managed to ‘recover’ a 47” deck gun from an abandoned navy sloop.

“The gun was inevitably named Big Bertha and was mounted on a concrete platform at the west end of Dunnet Beach- you can still see it if you look with the ring of bolts for mounting the gun and the letters RAF picked out in pebbles at one side.”

Somehow Atcherley had managed to obtain 130 rounds of ammunition for this gun from the Royal Navy depot at Chatham.

Pioneer Corps volunteer

A bacon slicer proved to be the only bribe needed to find a volunteer to fire Big Bertha- it was all a corporal from the Pioneer Corps, accidentally left behind by his company needed to take up the challenge.

Therein also hangs an aside.

Drew relates: “This company of Pioneer Corps had arrived by train at

Wick and were unsure where they should report to.

“Atcherley heard about their predicament and, never one to let an opportunity go pass by, he shanghaied the lot of them and brought them to Castletown. They carried out many odd tasks about the station until someone discovered they should have been in Hackney Wick in London.”

Drew also learned from a local resident that Atcherley was prone to suddenly stopping his vehicle dead in the middle of the narrow local roads, getting out and charging up a hill or through a field to go an investigate something, holding up the traffic until at length he returned and drove on.

The base continues to take shape

It took a year or so to turn RAF Castletown into more than three grass runways and a collection of nissen huts and wooden sheds.

The aircraft were originally serviced under canvas.

Drew said: “Imagine this in a raging blizzard.

“The winds were so severe that the aircraft had to be tied down with huge screw pickets.”

Gradually more buildings were requisitioned for base, and life got a bit more comfortable, despite the vast increase of people who all needed to be housed, fed and watered.

There were officially 1227 personnel, including 60 officers and 113 Senior NCOs, but adding in personnel of two squadrons usually stationed at the base, Pioneer Corps carrying out maintenance and construction work, war ministry engineers , civilian contractors for heavy construction work, the RAF regiment in charge of station defence and the WAAFs, upwards of 2,000 is more accurate.

Castlehill House by the harbour became station HQ and HQ officers’ mess.

The new school building, old school building, infants school, Drill Hall, Free Church hall, ex-servicemen’s club and the Masonic Lodge were taken over as

sleeping accommodation for airmen.

Part of the headmaster’s house became the sick quarters for a while.

The old Mill housed the army unit for the defence of Dunnet Bay while the Dunnet Hotel was the squadron officers’ mess.

The Established Church was converted to become first the airmen’s mess.

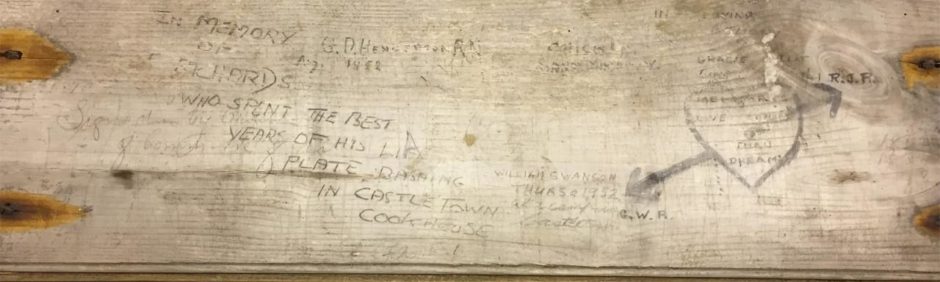

Intriguing graffiti from the time came to light there during the churches’ modern renovation.

Neil Buchan of Castlehill Heritage Centre recalls: “Next to the church was the cookhouse.

“A clear message pencilled on one panel says “in memory of F Richards who spent the best years of his life plate-bashing in the cookhouse.”

“Local war-time romances are perhaps implied in the inscriptions “In loving memory of Gracie Dallas Sept 1941” and “memories live longer than dreams” encircled by a heart and arrow.”

Wartime romances

Drew also remembers hearing about one particular wartime romance.

He said: “There was a young lass in the village who was in an office when a group of four or five airmen appeared looking for directions to the new aerodrome.

“She took a shine to one and spotted him later at a dance.

“They ended up getting married.”

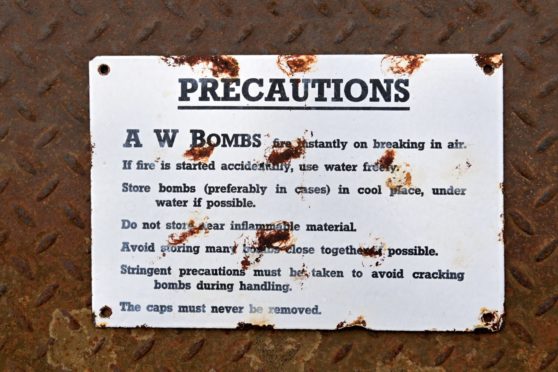

Meanwhile, the Castletown fighters were kept busy with patrol duties.

At the beginning of May 1941 No 124 squadron was formed at the base with an operational strength of 18 of the new Mk1 Spitfires.

Drew said: “Their offices are one of the few buildings still standing at Castletown, beside the Greenland road.

“Someone has inscribed 124 on the concrete path just beside the door.

“Its main duties were flying the usual coastal and convoy patrols, as well

as post training flying experience for new pilots to introduce them to operational

flying before being posted to units in the south.”

Inevitable accidents

Inevitably were accidents, one particularly tragic.

An exuberant young Canadian pilot, William Keegan, performed a victory roll while coming in to land in his new Spitfire.

Unfortunately he misjudged his height and ran through a wall, the aircraft disintegrating and scattering.

Keegan died from severe internal bleeding.

The 20 year old was defying an order from above not to perform victory rolls- four days earlier he had performed one coming into land, incurring wrath from the squadron commander.

One accident led to the amazing discovery some fifty years later of a connection between RAF Castletown and The Great Escape from Stalag Luft III.

Escaping the worst of rationing

But airmen found there were advantages in coming to this remote outpost.

In such an agricultural area, they could escape the worst of rationing by dining at Betsy’s Cafe- bacon and eggs was still on the menu.

Rations were supplemented by the station garden which produced 800 lettuces, and 6000 onions and leeks.

The Officers’ Mess also kept lobster pots in the bay.

Officers could spend their off duty hours shooting deer at Berriedale and dining on the venison at the Dunnet Hotel.

They shot mallard and widgeon at Loch Heilan and took grouse from the moor.

Christmas 1941

Christmas 1941 must have been memorable, with a slap up turkey dinner and Christmas pudding produced for around 1000 airmen.

Each was given a bottle of beer, an apple and 10 cigarettes.

By March 1942 they had a station cinema with two performances daily.

A concert party followed, with regular shows in the new cinema.

A squash court was built for officers, and the station had its own soccer, squash, hockey and cricket teams, competing regularly with other local services.

But life went on under a dark shadow.

Drew said: “Caithness and Orkney took a lot of aerial attacks while the phoney war was going on down south.

“Orkney was worse, with mass bombing attacks taking place from the start of the war.

“There were 100 search light batteries on the islands which lit up during an air raid.

“Children of the remembered the scene vividly, the sound of the bombers and the explosions, just across the firth.

“Aircraft from Castletown would be involved in the defence.”

After 1943, the war theatres had shifted south, and things began to unwind on the base.

The personnel drifted away to other postings and the station soon reverted to a Care and Maintenance status.

Sheep return

The Dundee Courier reported on November 7 1945: “Two Caithness RAF aerodromes, Castletown and Skitten, which played an important part in the defence of Britain and the attack on Germany, are now to play a different role- this time in the nation’s food resources.

“Both dromes have been let to farmers for grazing, the the warlike roar of fighters and bombers has given place to the peaceful nibbling of hundreds of sheep.”

It took a while for the re-settled Polish contingent to leave though.

The Courier of November 25 1947 reported that the last 100 had taken a special train south from Thurso, adding: “Between two and three thousand Poles were stationed in the former RAF camps at Castletown, Skitten and Dounreay, which were called Polish Recalcitrants Camps.

“Now only four Poles remain at each camp as temporary caretakers.”

There might have been a sigh of relief when they left.

Neil Buchan of Castletown Heritage Society said: “The behaviour of the Polish soldiers after the war was less than disciplined, with incidents of brawling and a stabbing in Castletown, which resulted in government action to station extra British troops here to maintain peace and order.”

The land was de-requisitioned in 1961, and bought back by the current owners.

None the less, the base retained an important place in local society for several decades.

Thanks to the generosity of the owners, all young people on the Thurso side of the county learned to drive on the runways.

Drew said: “The runway ended at the road. I remember when very small sitting on my dad’s lap steering while he operated the pedals.

“There was go-karting, model flying, stunt driving shows, and a flying club with its own aeroplane.”

“Nowadays, we frequently get the families of ex-servicemen based in Castletown coming back to have a look.”

The booklet ‘Castletown Recalls 1939-1945’ is available at Castlehill Heritage Centre.