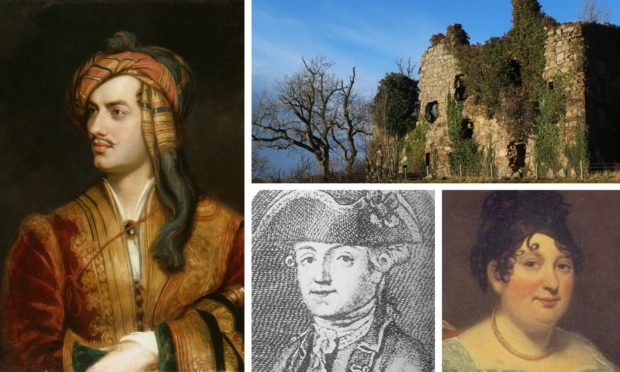

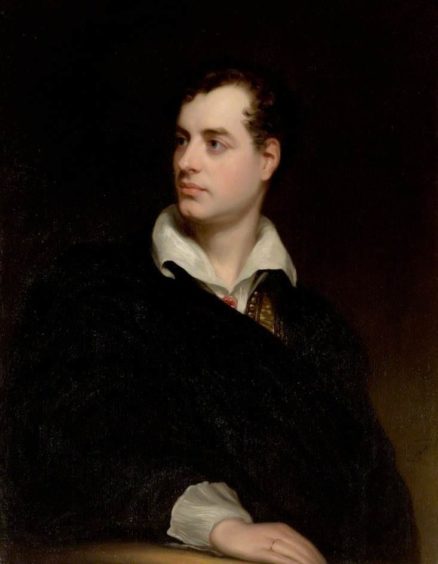

Mad, bad and dangerous to know – so one of Lord Byron’s many lovers dubbed him.

The poet spent his formative years in Aberdeen, leaving Scotland as a 10-year-old in 1798 when he became the 6th Baron Byron.

What part did his northern roots play in the drama of his life?

By 1816, mired in debt and sex scandals he was in permanent exile abroad.

It all went finally wrong for George Gordon Byron after accusations of incest with his half-sister, Augusta Leigh.

A discontented and eccentric lover, Lady Caroline Lamb made sure the word was spread throughout high society – it was she who described him as ‘mad, bad and dangerous to know’.

Byron possibly had a child with Augusta, something London society wasn’t prepared to overlook, and despite his riches and status as one of the greatest English poets and leading lights in the Romantic movement, he fell massively from grace.

Even considering the dissolute, decadent Regency period in which he lived (1788-1824), academics agree that Byron’s sexual attitudes and behaviour were extreme, and conditioned by his parentage and early experiences in Aberdeen.

‘Mad Jack’ Byron

His dissolute father deserted the family, leaving him with a vile-tempered mother and a sexually abusive nursemaid.

A clue might be in the nickname of his father, John Byron (1757-1791).

Known as Jack, he was described as ‘Mad Jack’ in an obituary of his famous son.

He was born in Plymouth, educated at Westminster School and became a captain in the Coldstream Guards.

The regiment was sent to Philadelphia during the American Revolution where the profligate Jack managed to run up considerable debts, a pattern he pursued throughout his life.

Back in London, he blew a £3,000 inheritance at the city’s tailors, hatters and sword makers, and took up residence in Pall Mall, embracing the life of a rakish young bachelor.

It wasn’t long before he was embroiled in a scandal that would change the course of his life, and eventually drive him towards Aberdeenshire.

He spotted the beautiful Amelia Osborne, Lady Carmarthen, during summer festivities at Coxheath military camp in Kent and the two embarked on a passionate affair.

The only problem was Amelia was married, and the pair recklessly flaunted their ‘secret’ relationship at Amelia’s Grosvenor Square home while her husband was away.

Upon discovery, Amelia eloped with Jack, pregnant.

Divorce followed, and in one fell swoop Amelia lost her lavish lifestyle, her place in society and guardianship of her three children.

Brutal and vicious

Jack was reputed to be brutal and vicious towards her, and the marriage was not happy.

Their first two children died in infancy, and Amelia herself died, probably of tuberculosis, a year after giving birth to Augusta Mary, the poet’s half-sister.

Jack found himself reviled by society, and badly in need of funds having squandered his way around Frankfurt, Paris and northern France for a while.

Family members persuaded him to return to England, and he headed for Bath in search of a wealthy wife.

Enter Catherine Gordon, a 22-year-old orphaned heiress taking the waters under the protection of her great-uncle, Admiral Duff.

She was the 13th Laird of Gight, having inherited the Gordon family estates.

(The genealogy website, Find My Past has just released a font of documents relating to the Gordons of Gight.)

Catherine stood out.

A 19th century account of her is less than flattering: “Though she had royal blood in her veins and belonged to the superior branch of the Gordons, it would not have been easy to find a gentlewoman whose person and countenance were less indicative of ancestral purity.

“A dumpy young woman, with a large waist, florid complexion, and homely features, she would have been mistaken anywhere for a small farmer’s daughter or a petty tradesman’s wife, had it not been for her silks and feathers, the rings on her fingers, and the jewelry about her short, thick neck… even in her twenty-fifth year she would waddle through drawing-rooms and gardens on the development of her unwieldy person.

“Miss Gordon’s education was very much inferior to the education usually accorded to the young gentlewomen of her period.

“Unable to speak any other language, she spoke her mother tongue with a broad Scotch brogue, and write it in a style that in this politer age would be discreditable to a waiting-woman.”

Could it have been her £23,000 fortune which first attracted the entirely broke and unscrupulous Jack Byron?

She was drawn to his good looks and entranced by his fine dancing – he spotted the opportunity and they were married within weeks, in such a whirl that Catherine later told relatives: “I was married on the 12th or 13th of May, I don’t know which, 1785 at St Michael’s church, and this is all I can inform you about it.”

Disappointment hit home fast when Jack discovered that Catherine’s wealth was tied up in land, and they would enjoy only a modest income at Gight Castle, a hunk of tower house some 25 miles from Aberdeen.

Catherine, completely infatuated, was bewildered when her husband showed his true colours in packs of lies and hot temper, and allowed her own violent mood swings to flourish.

Where previously a local composer had written a reel in her honour, Miss Gordon of Gight, they were now dancing to a different tune with the words:

Where are ye gaeng, bonny Miss Gordon?

O where are ye gaeng, saw bonny and braw?

Ye’ve married wi Johnny Byron,

To squander the lands o’Gight awa’.

This youth is a rake, frae England is come,

The Scots dinna ken his extraction ava;

He keeps up his misses, his landlords he duns,

That’s fast drawn the lands o’Gight awa’…

On the death of his father, Jack discovered that he’d been virtually disinherited.

To pay off his debts, Gight was sold to Lord Aberdeen for £18,000, leaving the couple with only around £5,000.

One agent estimated their expenditure in their first eighteen months of marriage to be almost £9,000 – around £700,000 in modern currency.

Mad Jack’s antics recorded

There’s a telling article in the P&J about ‘Mad Jack’, from December 11, 1928.

It describes Catherine as a ‘cross, spoiled creature’ and Mad Jack as ‘more than half daft’.

He seems to have encouraged the estate workers to drink and dance from morning until night.

He shot birds every time he was out and would buy them back from the tenants for whatever coin came to hand from his pocket, which could even be a whole crown.

Catherine’s reaction to this was not thought to be rapturous.

On one occasion Mad Jack rode his favourite horse up the outside stair of Gight church, and almost in the door, “when the decent male worshippers got hold of the horse and pushed him back ‘efter the tail’. The mad rider never came off all the time until he was down on level ground.”

Mad Jack then dismounted and paid a woman handsomely to lead him out to the minister’s stable.

The poet is born

The couple took off for France, but without Jack, Catherine ended up in lodgings in London to give birth to their only child, George Gordon Noel Byron on January 22 1788.

Catherine named him after her own father George Gordon of Gight, a descendant of James I of Scotland, who died by his own hand in 1779.

She soon headed north to home territory.

Mad Jack made a reappearance in lodgings she had taken in Queen Street, Aberdeen, but was quickly sent on his way.

Catherine was depressed and being driven deeper in debt by Jack’s continual demands for money.

He eventually died, probably of TB, in France in 1791.

Byron’s childhood

After Jack’s death, Catherine’s circumstances were even further reduced, and she and the young poet-to-be moved to Broad Street, Aberdeen.

George was by all accounts, intelligent, rebellious and troublesome, often falling out with his mother.

He attended Aberdeen Grammar School, where he learned the rudiments of a classical education.

Latin displeased him so much he vowed he hated poetry.

But it’s considered Aberdeen played an important part in his cultural heritage.

He was an assiduous reader of library books, and often visited the theatre.

But traumatic emotions coloured his formative years.

He blamed his mother for his deformed foot and frequently told her how much he hated her.

Sexual abuse by servant

He was sexually abused by the family servant, May Gray from the age of five, keeping this to himself until he confessed it to a solicitor when he was 10, at which point Gray was dismissed.

But the emotion and confusion would never leave Byron – those who have studied his life agree the sexual license for which everyone knew him, had its origins in this childhood trauma.

Another May taxed his sensibilities – aged eight, he fell madly in love with his cousin May Duff when they met in Deeside or Aberdeen, with an emotional intensity hard to comprehend.

He went into convulsions years later when he heard she was getting married.

When Byron’s great-uncle, posthumously labelled the “wicked” Lord Byron, died on 21 May 1798, the 10-year-old George Gordon became the sixth Baron Byron of Rochdale.

He moved from Aberdeen to the ancestral home, Newstead Abbey, in Nottinghamshire, heir to the equivalent of £9m.

Following in the footsteps of his father, his life proceeded coloured by scandal and debt, affairs with married women, actresses and young men to the point that he had to exile himself abroad.

But in his work he hints of his love for his northern roots.

In Hours of Idleness, penned when he was 19, he writes:

England! They beauties are tame and domestic

To once who has rov’d on the mountains afar

Oh! For the crags that are wild and majestic

The deep frowning glories of dark Loch na Garr.

See more like this: