They were men from communities all across the north and north-east of Scotland who endured unimaginable horror in the Far East.

They were forced to work on such grim projects as the Death Railway and Hellfire Pass and many of the Gordon Highlanders who served in the Far East never returned.

The Second World War finally ended on August 15 1945 with the surrender of Japan, which offered a merciful release for the surviving members of the 2nd Battalion Gordon Highlanders who were captured when Singapore fell early in 1942.

In the aftermath of one of the worst setbacks during the whole conflict, around 60,000 men of the British and Australian forces were captured and became prisoners of war.

At first, the Japanese did not know what to do with so many captives and, having signed but never ratified the Geneva Convention, which was supposed to safeguard the PoWs’ welfare, they cared little for their wellbeing.

Prisoners were used as forced labour

After bombing Pearl Harbor and Singapore virtually simultaneously on December 7 1941, the Japanese swiftly took control of large parts of south east Asia and set their sights on conquering India.

They attacked the latter country through Burma and supplied their forces by ship, but many of these vessels were sunk by the Allies operating from bases in India.

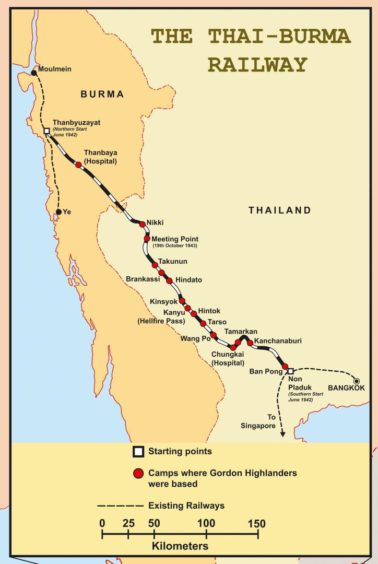

That convinced them they needed an overland route to Burma, so they decided to build a railway through Thailand and Burma, which would be linked to Singapore, where a railway line to Bangkok already existed.

This meant laying a railway line for a distance of almost 250 miles through dense, uncompromising jungle in mountainous terrain with a harsh climate where tropical diseases such as malaria, cholera and dysentery were prevalent.

The Japanese authorities expected to complete the railway in under 12 months but in such difficult country it was impossible to import mechanical means to aid construction.

They did, however, have a huge pool of expendable free labour and the only thing that mattered to them was that the railway was completed urgently.

In October 1942, the Japanese began to move thousands of their PoWs up to Thailand by train to start construction of the railway.

These so-called trains were, in reality, metal box cars which were blazing hot by day and freezing cold at night and the PoWs had to endure these conditions on a five-day, non-stop journey with very rare stops for water or food and no provision for toilet breaks.

On arrival in southern Thailand, the first task was to erect bamboo huts as sleeping quarters, but construction of the railway was given precedence.

Stewart Mitchell, the volunteer historian at the Gordon Highlanders Museum in Aberdeen, has chronicled the stories of these poor fellows and written a book, Scattered Under The Rising Sun, about the appalling conditions they experienced.

He said: “We only know the fate of many of the men through the bravery and cunning of Sergeant Dick Pallant, who completed a list of every man in the battalion before the fighting began in 1941 and updated his record about almost every man.

“This was at great personal risk, as the Japanese forbade the keeping of a diary or other records and he would have been severely punished or possibly even executed if the record had been found.

“This record now forms part of the collection of the Gordon Highlanders’ Museum.

The Gordons death toll was grievous

“Among these men forced to work on the Thai-Burma Railway were hundreds of 2nd Battalion Gordon Highlanders. Of the 1,000 Gordons in Singapore, almost 400 had perished by VJ Day.

“Many of these soldiers were at Nikki, on the Thai-Burma border, where they worked on the Kanyu cutting, which was some 400 yards long through solid rock.

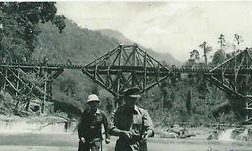

“The Kanyu cutting was done by hand, using nothing more than hammer and chisels to drill holes into the solid rock, into which was placed a stick of dynamite to blast the rock. The rubble was then removed laboriously by men with baskets.

“These explosions took place even though other PoWs were working nearby who were often caught by splinters of sharp rock which caused many injuries which were invariable liable to infection, which could lead to the amputation of limbs.

“With the need to complete the railway, the Japanese forced their captives to work for 18 hours every day, continuing after darkness.

“At Kanyu, the Japanese lit bonfires of bamboo to give light.

“For the PoWs looking down into the cutting filled with fires and witnessing their comrades toiling, almost naked and emaciated due to malnutrition and disease, it was like a vision of hell. Kanyu cutting was therefore christened Hellfire Pass.”

Some survived but many others perished

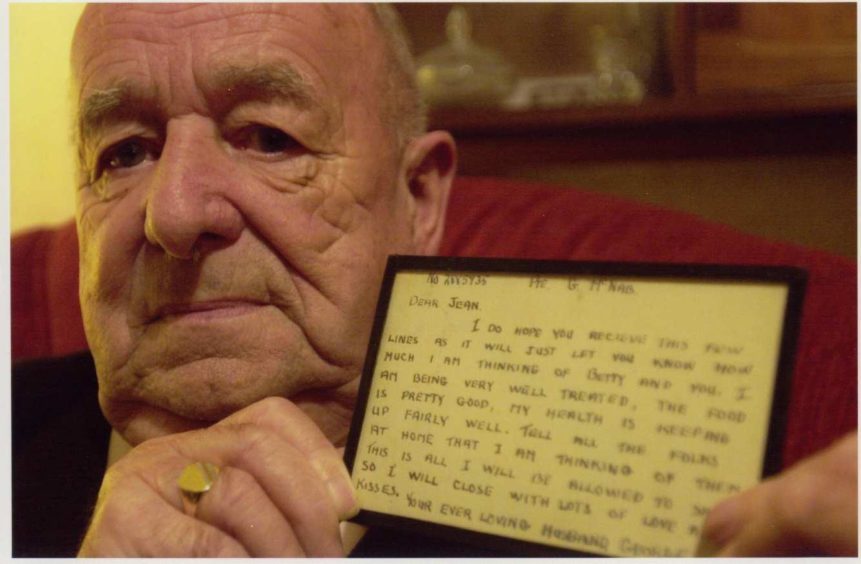

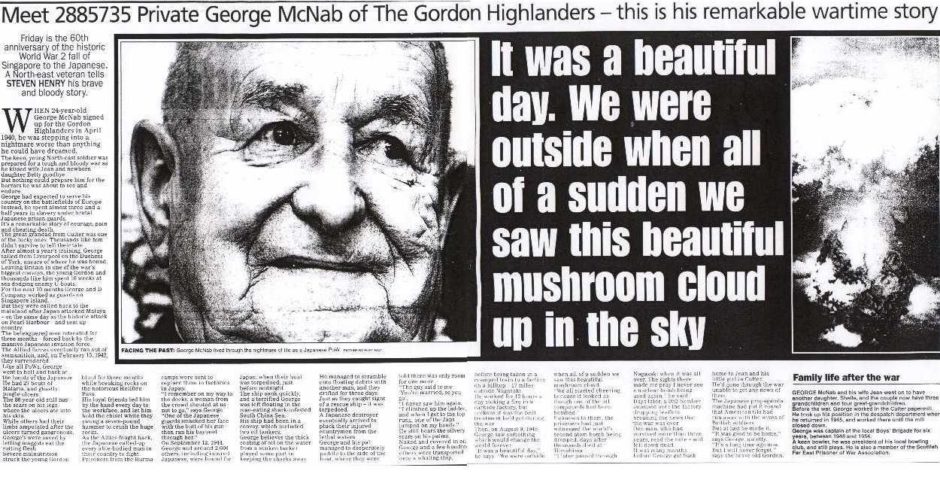

George McNab, from Peterculter, was sent to Thailand in April 1943 as part of “F Force” and was fortunate to survive an awful series of privations.

He developed temporary blindness for four months, due to malnutrition as a result of the poor diet of watery rice with no vegetables or meat.

He was required to continue working in the Kanyu cutting, despite his disability, or he would have been denied any food.

But he was saved with the valuable assistance of his fellow Gordon Highlander Sergeant James “Tibby” Burnett, from Turriff.

The latter tied a rope to George and they worked together, with him holding the chisel while Tibby wielded the hammer.

To make matters worse, George had no fewer than 14 attacks of malaria and his legs were a mass of infected jungle ulcers, which meant that – eventually – he had to be evacuated to Chungkai Hospital where he was treated by a British doctor.

The hospital facilities were extremely rudimentary but the medical staff worked miracles with home-made equipment, despite having precious few drugs.

After his recovery, he was taken to Singapore, as the prelude to being sent to Japan aboard the Kachidoki Maru.

Disease was rife among the prisoners

The battalion was a close-knit group and many of the men were related, with some 56 sets of brothers in the ranks.

James and Peter Milton, brothers from Aberlour, joined the Gordon Highlanders together on the same day in May 1933.

They were both sent to Thailand but James was with the ill-fated “F Force” at Kanyu, where he fell sick with dysentery, which afflicted many of the PoWs due to the poor sanitary conditions of the camps.

He was unable to survive the harsh conditions and died at Kanyu on May 28 1943 and is buried in Kanchanaburi War Cemetery, Thailand.

He was one of more than 60 Gordons who died of this terrible disease.

The deadliest of all the diseases faced by the PoWs was cholera. An outbreak in northern Thailand, around Nikki, caused the deaths of 38 Gordons who were working on the railway.

One of the first men to die this terrible death was Andrew Williamson, who was among 18 Fraserburgh men serving in the battalion. He died at Nikki on May 30 1943.

James Scott, from Braemar, had the awful job of cremating his comrades on pyres of bamboo.

His gruesome task was made all the more difficult in the wet monsoon season, as it was almost impossible to keep the fires burning and he had to beat off the vultures trying to feast of the corpses.

The Speedo regime took a heavy toll

Three brothers from Keith in Banffshire, John, Arthur and Alexander McGregor, were all serving together when captured and they suffered throughout their incarceration.

They were despatched to Thailand to work on the railway. John and Alexander arrived in October 1942, but Arthur was not sent there until April 1943 as part of “F Force”, which was probably the most unfortunate group of men to work on the railway.

When the Japanese realised their wholly unrealistic target for completion was not going to be met, they forced more PoWs, including those who were not fully fit, to work.

This was the so-called “Speedo” period, when the guards would constantly harass the men by shouting “speedo, speedo” to urge them on and brutal beatings often accompanied these verbal encouragements to work harder and faster.

Arthur and John survived the horrors of the conflict but on completion of the railway, in October 1943, Alexander was selected to be sent to Japan.

The Japanese were low in manpower with the majority of their military-age men having already been conscripted into their armed forces, so they used the PoWs to work in their home industries.

No escape at sea for many Scots

Mr Mitchell said: “The journey to Japan was extremely dangerous as the American Navy had control of the Pacific and was sinking every Japanese ship they encountered.

“Alexander set sail from Singapore on the Hofuku Maru, which was sunk by carrier-based aircraft on September 21 1944 and, unfortunately, he was lost at sea.

“He was one of the 72 Gordon Highlanders killed in this way that month. Brothers John and Henry Elder, from Inverbervie, Kincardineshire, were both on the Kachidoki Maru, which was sunk on September 12 1944 by the submarine USS Pampanito.

“John drowned but Henry was rescued by the Japanese and taken to Japan, where he died of exposure and pneumonia just a month later.

“Only a few others, such as George McNab, were lucky enough to survive the shipwrecks.

“When the Kachidoki Maru was hit by torpedoes, George managed to escape and clung on to a damaged raft with his friend, Alistair Paris.

“They floated close to each other for a time but soon drifted apart. As Alistair was almost out of earshot, he shouted to George: ‘If I survive this, I am never leaving the Black Isle again’.

George witnessed a giant mushroom cloud

“He did survive and was true to his word. George was rescued two days later, suffering from burns and cuts from the sinking ship, and taken to Fukuoka PoW Camp, where he was forced to work in a carbide factory and a foundry where the heat was unbearable.

“In Fukuoka, near Nagasaki, on August 9 1945, George was being marched to work when he saw a large bomber in the sky.

“Shortly afterwards, there was an enormous flash and what he described as a “beautiful” mushroom cloud.

“It was the dropping of the second atomic bomb, which heralded the end of the war as the Japanese surrendered unconditionally just six days later.”

The PoWs were soon liberated and returned home to Aberdeen, Aberlour, Arbroath and many other communities across Scotland, but many of them never fully recovered from the mental and physical scars of their horrific treatment.

For a long time, they were regarded as The Forgotten Army and the majority of these brave men are no longer with us.

But what they went through should never be forgotten.