You could make an argument for Edinburgh Castle, the Scott Monument or Skara Brae being Scotland’s most iconic building or structure.

But, for many people, nothing comes close to emulating the Forth Bridge, the great Victorian work that has featured on banknotes and coins, appeared in classic films such as Alfred Hitchcock’s The 39 Steps, been classified as a Unesco World Heritage Site and gained public recognition as the country’s greatest man-made wonder.

It has even entered the dictionary: the phrase “it’s like painting the Forth Bridge” becoming synonymous with a never-ending job.

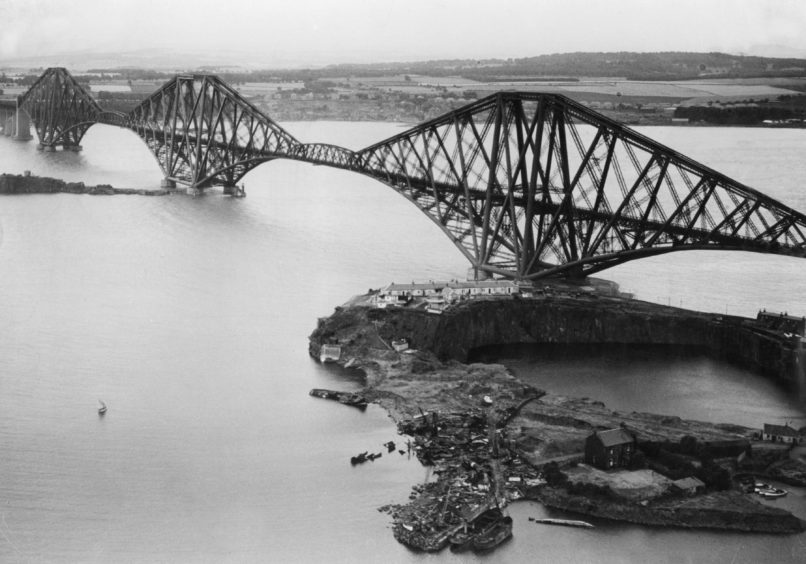

And despite the construction of two other majestic structures across the Forth, the original remains the most popular.

Yet when the idea of connecting the Lothians and Fife was first mooted in the early 1870s, and it was agreed that a new crossing was essential to cut journey times, the authorities handed responsibility for the project to Sir Thomas Bouch, who was already creating another bridge for the North British Railway – across the Firth of Tay.

And, if it had been left in his hands, we would never have witnessed the creation of the famous cantilever edifice that is viewed as a miracle of engineering.

Christopher Valkoinen works in the Search Engine library and archives at the National Railway Museum in York, where he manages the digitisation of myriad engineering drawings and other materials, some of them dating back centuries.

He is also a qualified steam locomotive fireman who is clearly in love with trains and machinery and the minutiae of how Britain’s vast transport network was established.

As the author of Railways: A History in Drawings, he has methodically highlighted the care and precision which underpinned the efforts of different companies to carry out ground-breaking work throughout the UK as demand for services surged.

But he hasn’t glossed over the cases when things didn’t go according to plan – and nowhere was that more evident than in the north-east of Scotland.

As he said: “From the late 1840s, railways reached north of Edinburgh to Perth, Dundee and Aberdeen, but all these routes involved either crossing the river (Forth) by use of a train ferry or a circuitous route via Stirling that was over 30 miles longer.

“A bridge was sorely needed and the task was given to Sir Thomas Bouch. For the Forth, he designed a suspension bridge with a central pier on Inchgarvie Island.

“However, work had just started on the venture when, in December 1879, the Tay Bridge collapsed as a train crossed in a storm, killing more than 60 people.

“The report into the disaster firmly laid the blame on Bouch, who was subsequently disgraced as an engineer and work on his version of the Forth Bridge was cancelled, (while he never recovered from the catastrophe and died the following year).

“He was replaced by two engineers, John Fowler and Benjamin Baker, who proposed a cantilevered design, using two large spans, each of 1,700ft.

“These were the longest cantilevered spans of any bridge in the world at the time and only the Quebec Bridge in Canada (constructed in 1919) has ever surpassed them.

“In response to the Tay Bridge disaster, where defects in the iron used had contributed to the collapse, Fowler and Baker chose to build the new bridge entirely from steel – it was the first time any structure in Britain had been built exclusively from this material.

“At 360ft above high water, it was also the highest edifice in Britain, except for the spire of Salisbury Cathedral and the dome at St Paul’s Cathedral (in London).”

It was a vast and hazardous undertaking, which was often carried out in storm-tossed or frozen conditions, in an era long before the advent of health and safety regulations.

At the peak of the work, about 4,600 men were employed on the construction and it has been estimated that as many as 73 of them perished while involved in the venture.

There’s one famous image of a riveter walking up one of the cantilever spans, eating a sandwich, with a cigarette in his hand, and he looks as if he is enjoying a Sunday stroll in the park, rather than standing without a harness miles above the water.

The Sick and Accident Club was founded in 1883, and membership was compulsory for all contractors’ employees.

It provided medical treatment to men and sometimes their families, and would pay them if they were unable to work.

The organisation also paid for funerals within certain limits, and offered grants to the widows of men killed or the wives of those permanently disabled.

Eight men were saved from drowning by rowing boats positioned in the river under the working areas.

But despite the problems caused by the weather and the challenge of bringing the scheme to fruition, Fowler and Baker were painstaking in their execution.

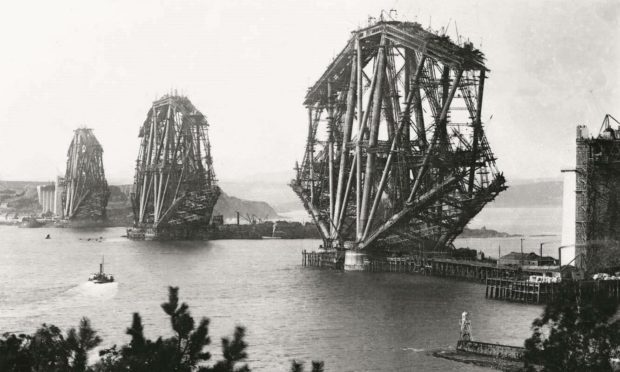

Mr Valkoinen added: “Construction began with the foundation for the three main piers, as well as the approaches on each side of the Forth.

“The main structure was then built up from the piers, gradually reaching outwards towards each other.

“Each new addition was mirrored on both sides of the pier to ensure that the extra weight was counterbalanced.

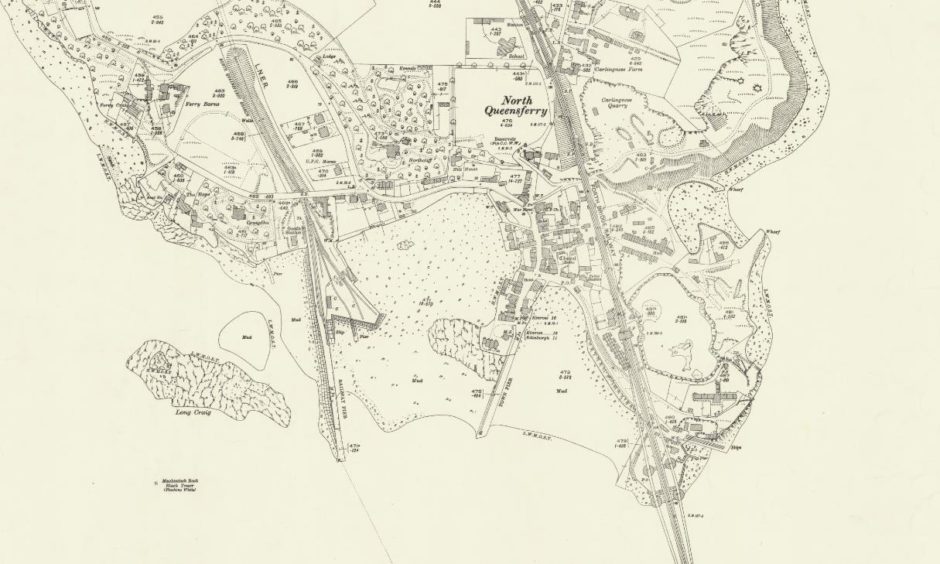

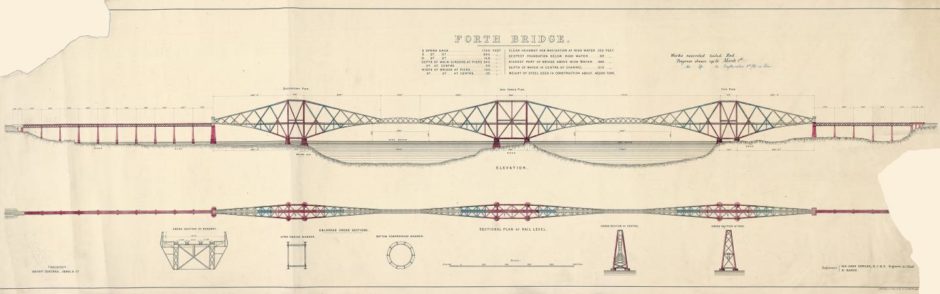

“The drawing reproduced here (above) tells the fascinating story of the bridge’s construction.

“As each section was completed, it was tinted red on the drawing (the erased pencil marks next to the date show that this was done several times) with the last of the red tints being added in March 1888.

“The areas tinted in blue show how the structure progressed over the next six months to September.

“And the bridge was opened on March 4 1890 by the Prince of Wales (who was later Edward VII) after taking eight years to be completed.”

Prior to the opening of the Forth Bridge, the railway journey from London to Aberdeen had taken about 13 hours, running from Euston and using the London and North Western Railway and Caledonian Railway on a west coast route.

However, once the new structure was in place, competition intensified along the east coast route from the Great Northern, North Eastern and North British railways and starting from King’s Cross, with unofficial racing occurring between the two consortia, which drastically reduced the journey time to about 8½ hours on the overnight runs.

This reached a climax in 1895 with sensational press reports about the “Race to the North” which spoke of trains travelling at breakneck speed during the day and night.

Thankfully, the new bridge proved up to the challenge.

The new book – Railways: A History in Drawings, published today by Thames Hudson – includes a wealth of evocative pictures, drawings, maps and photographs of some of the most famous names in the history of British railways.

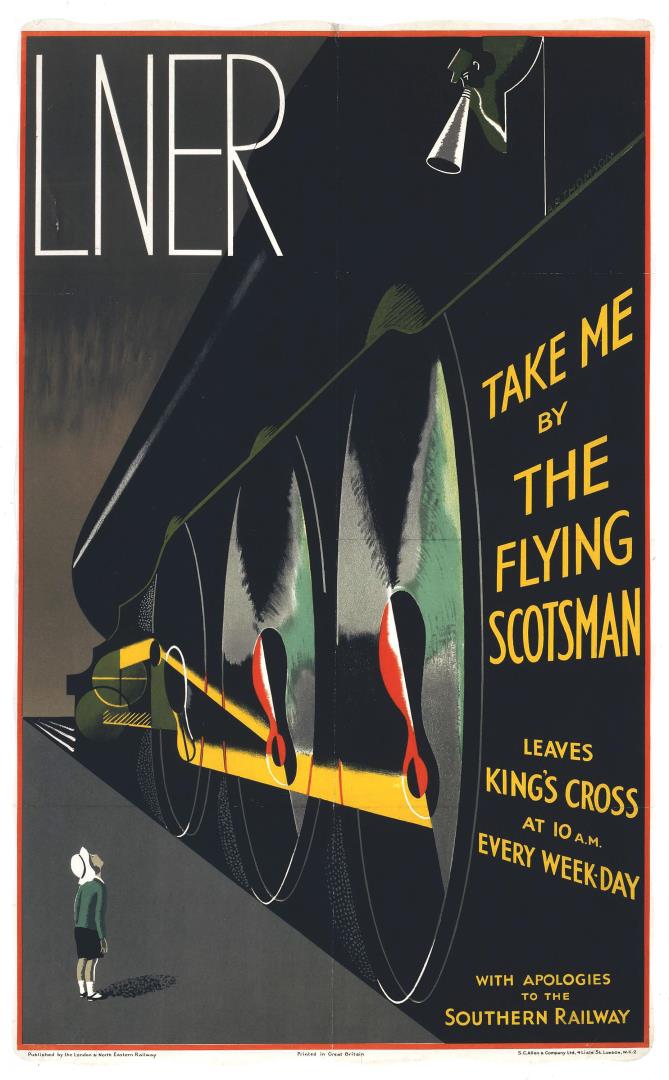

And there is a romantic mystique to an art deco poster for the Flying Scotsman, the famous passenger train that operated between Edinburgh and London on a regular basis via the East Coast Main Line.

The service began as far back as 1862 and although the distinctive name was not officially adopted until 1924, it has become part of transport lore and still commands audiences of youngsters, aged from seven to 70, whenever it embarks on its journeys.

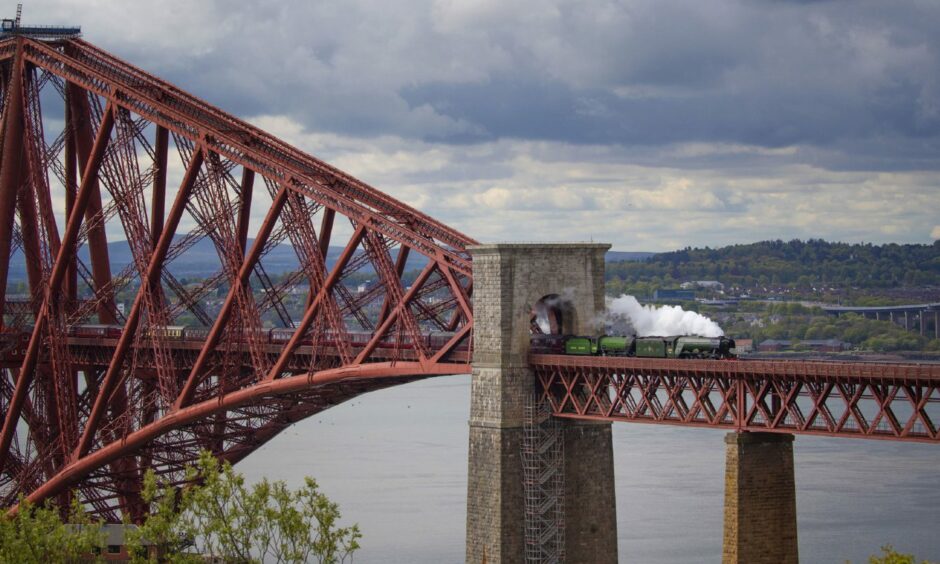

One of the photographs captures the Flying Scotsman travelling from Edinburgh to Inverness and where else would it be pictured than on the Forth Bridge?

There may be three imposing structures across the river, but while the Forth Road Bridge possessed an elegance all its own when it was unveiled in 1964, increasing traffic and corrosion of the steel suspension cables forced the Scottish Government to create the replacement Queensferry Crossing, which opened in 2017.

At various stages, the oldest of the structures has been covered with the construction equivalent of sticking plaster. But it has prevailed down the decades.

As Mr Valkoinen says: “In contrast, the first Forth Bridge, at 130 years old, is estimated to have another century of life left, provided that it is properly maintained.”