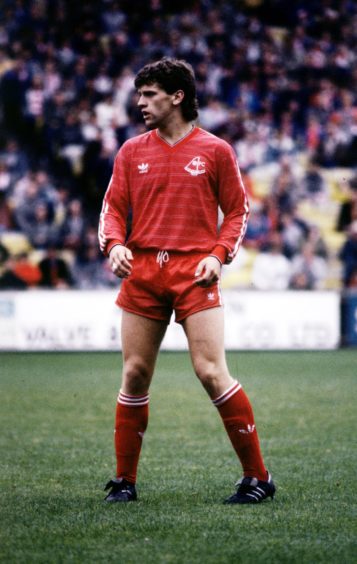

It’s hard to imagine these days how regularly the likes of Eric Black enjoyed picking up trophies to the stage where it almost grew routine.

Even as a teenager, the Bellshill-born player who moved up to Nigg with his family when his father secured a job in the burgeoning north-east oil industry found himself at the centre of high-profile matches where any nerves were soon dissipated by the realisation he was part of a unique period in Aberdeen FC’s history.

Black, who enjoyed basketball, was adept at out-jumping opponents and frequently left defenders clutching at shadows, so it’s hardly surprising that his elevation was swift after he was spotted by goalkeeping great Bobby Clark.

Yet, with hindsight, one wonders if he was thrust into too many contests as a teenager and in his early 20s, which explained why he was forced to retire at the age of 28.

Not that he was complaining about his pivotal role in the Pittodrie prize procession.

The celebrations arrived in a giddy whirl for Black after he made his first-team debut in Willie Miller’s testimonial match against Spurs (who included Steve Archibald in their ranks) in August 1981 – and although he was just 17, he was already beginning to learn the truth about what it required not only to meet and beat these formidable opponents, but also continue to satisfy the exalted standards of Alex Ferguson.

It was no longer enough to be content with second or third place in the league or finish on the wrong side of an “honourable” defeat in a Cup final. As Black recalled, the attitude in the dressing room as the Dons’ reputation increased through Europe was that rivals should be scared and intimidated by them, not the other way around.

And it worked. Ferguson had instilled such a positive winning mentality in his troops that they never even considered the possibility of losing in showpiece finals.

They were by no means favourites when they travelled to Glasgow to tackle Rangers in the 1982 Scottish Cup final, not least because no club from outwith the Old Firm had lifted a domestic trophy in more than 10 years, but that didn’t matter.

Instead, after Black came off the bench to help Aberdeen score three goals in extra time and record a resounding 4-1 triumph over the ageing Ibrox line-up, it marked a quite remarkable spell for the youngster who collected eight major honours – including the European Cup-Winners Cup – in just 180 appearances from 1981 to 1986.

It had never happened before to anybody at Pittodrie.

And, to be fair, it will probably never happen again.

But Black and his confreres were in the stratosphere and became accustomed to jousting with giants and dealing with them the way David slew Goliath.

Yet, in retrospect, even he admits it was an extraordinary and “ridiculous” sequence of results which led to the Dons becoming the masters of their domain for several years.

He recalled: “No wonder I used to think we’d come, play a season, pick up two or three trophies, go on holiday for a few weeks, get a bit of sun and then come back and win another two or three! I didn’t know anything else.

‘I was extremely lucky in my career’

“I had nothing else to compare it to and you don’t really think about these things while you are playing. I was extremely fortunate to land with the quality of footballer that was around about me and the management team as well.

“But, of course, it’s quite ridiculous to pick up a trophy every 20 odd games, isn’t it? There are people that go through their careers and play 800 games and never lift a trophy, so I still count myself as being extremely lucky in that regard.”

The crowning moment was Gothenburg and a 2-1 success over Real Madrid in 1983. No matter how many times it is mentioned, that outcome still induces the vapours among some supporters who were part of the crowd inside the saturated stadium in Sweden.

Prior to the Cup Winners’ Cup Final, Ferguson presented his illustrious opposite number Alfredo Di Stefano with a bottle of whisky – on the canny advice of Jock Stein in order to give the Real Madrid boss the belief that Aberdeen were just satisfied to be there in the European spotlight.

It was another piece of psychology which worked a treat, along with Fergie’s low-key build-up to such a massive game and his determination to focus on nothing else but the match itself, even if it meant keeping the media in the dark about such matters as injuries to Dougie Bell – who wasn’t in the match squad – and Stuart Kennedy – who made the cut, although Fergie knew that he wouldn’t be able to play.

As for Black, who opened the scoring for his team in the sixth minute, the whole occasion passed him by in something close to a blur. He was jubilant, but shattered, triumphant but knackered. Others hit the bar, but he went to his bed.

Black later told AFC programme editor Malcolm Panton: “The significant thing about Alex’s preparation was that he didn’t make a big deal of it. We were prepared as we always were and Archie Knox came back with a detailed dossier after watching them.

“We had covered their strengths and weaknesses during the week, but he played it down so that we wouldn’t be overawed because there was massive media interest.

‘It was a momentous achievement’

“His message was a bit like: ‘Yeah, they are a good team with a lot of good players but we can beat them’. And we certainly believed that. We weren’t in awe of them at all. Yes, we were respectful of them, but we knew we could compete with them.

“And, of course, we did more than that on the night. There was just the delight at the end of the game, just that unbridled joy when the full-time whistle sounded.

“You knew something had been achieved that was quite phenomenal, if truth be told. Regardless of whether you look at it now or look at it then. It was a phenomenal achievement, and to be part of that still makes me feel very proud.”

Just a few months earlier, in February 1983, Black scored a superb hat-trick in a 3–1 win against Celtic and, nearly 40 years later, he remains the last visiting player to achieve that feat at Parkhead. One might have anticipated he would have earned rich praise from the normally hard-to-please Ferguson.

Erm, one would be wrong.

On the contrary, Black said: “I remember getting hammered after the hat-trick at Celtic Park, he went daft. I think it was probably that he didn’t want me to get carried away.

“But I remember it to this day, I got absolutely slaughtered after the game. And that wasn’t abnormal, to be fair! I was only young at the time, so that’s the way it was. It certainly kept us in check, that’s for sure.”

In 1986, Black joined French club Metz after a deal with Arsene Wenger at Monaco had fallen through. He was still only 22 years old. Yes, he had attained all these medals and silverware at what seemed like the very outset of his football career.

But, although he still appeared in the first flush of youth, the injuries began to pile up. After five seasons with Metz, during which time he won the Summer Cup – the forerunner of the League Cup – within weeks of arriving in 1986 and the French Cup in 1988, he was forced to retire from the game due to a chronic back problem in 1988.

Ferguson later admitted that the problems suffered by Black and other youngsters whom he had managed at Aberdeen were due to them playing an excessive number of games at a young age. But that was the culture which existed in the 1970s and 1980s and it wasn’t as if there was no reward for the Pittodrie squad of that vintage.

Black, for his part, had few regrets about having to retire prematurely. And he was in loquacious mood when he was inducted into the Aberdeen Hall of Fame in 2019.

He recalled: “It’s really nice, we [the Gothenburg Greats] keep in touch, there’s a kind of WhatsApp thing that somebody set up, so there’s always one or two comments on that. But it’s nice, it’s got a nice feeling about it.

“You know, I think when you win things together, I think it definitely makes a stronger bond, and obviously the success we had up here made it even better.

“I find myself a lot of the time thinking about what good footballers they were, and how tough they were, and they could fight people, they could play against people, but they were good people, fundamentally decent people.”

As indeed is Mr Black himself.