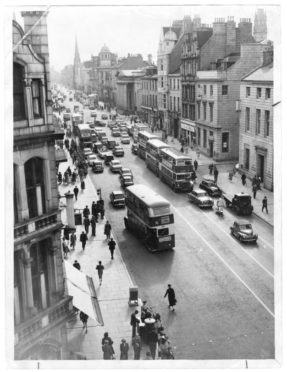

Can you imagine Union Street without the Music Hall? It is one of Aberdeen’s best-loved and most revered buildings, but it was earmarked for demolition in the 1960s.

Radical plans were put forward to completely redevelop the middle of Union Street by knocking down every building between Huntly Street and South Silver Street.

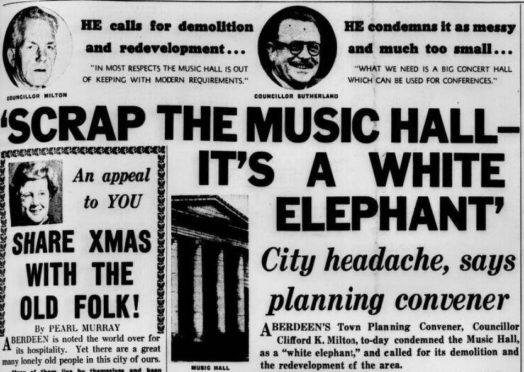

And in December 1961, the historic Music Hall was top of the hit list.

The concert hall, built in the late Georgian era, was worlds away from sexually provocative acts like Elvis Presley topping the music charts in the early 1960s.

City leaders considered the Music Hall old fashioned and unfit for purpose, in fact councillor and pioneering city architect T Scott Sutherland described it as a “morgue”.

Music Hall History

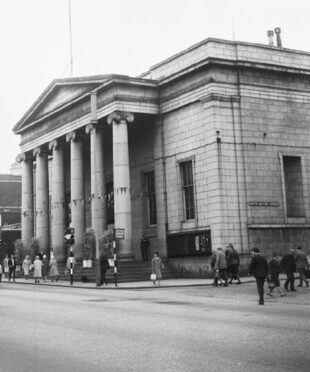

The Music Hall was designed by celebrated Aberdeen architect Archibald Simpson, initially as the city’s assembly rooms.

Opening in 1822, the assembly rooms provided a ballroom, billiards room, parlour and banqueting hall for the upper echelons of Aberdeen’s polite society to socialise and entertain.

But as the Victorian era progressed there was demand for a venue that could bring entertainment to the masses.

The banqueting hall was replaced with a concert hall big enough to house an orchestra, and the building reopened as the Music Hall in 1859.

Prince Albert travelled from Balmoral to chair the opening event at the Music Hall – a science conference.

And for decades, the hall remained a favourite place for music, fundraisers and talks, but its popularity waned with the arrival of the cinema age.

With its fortunes fading, the Aberdeen Music Hall Company sold the building to the town council for £34,000 in 1928.

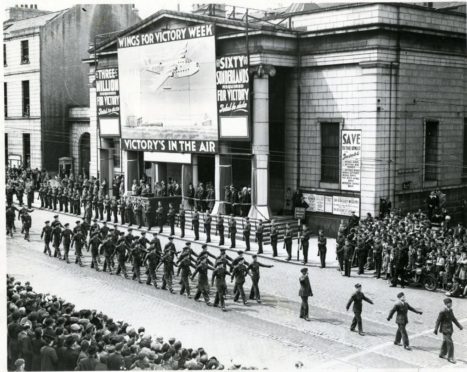

The hall was transformed into a roller rink in the interwar years and saw continued use as a venue, and was even used as a Post Office to deal with the Christmas rush during the 1930s.

But by 1961 was considered too small for the modern age with acoustics that were “less than satisfactory”.

As far as a legion of city councillors was concerned, this stuffy old building had to go.

‘The place is a morgue’

“I know I shall be bringing myself into conflict with certain sections of the community when I suggest that the whole Music Hall area should be demolished and redeveloped, but that is my opinion”, said Councillor Clifford Milton.

Developers Murrayfield Real Estate Company had approached the council about buying the Music Hall and surroundings buildings with a view to flattening the area to build shops.

Planning convener Mr Milton and many of his council colleagues thought this was a dream opportunity to offload some of Union Street’s dreary old properties in pursuit of progress.

He added: “The Northern Club has remained empty for years and the Music Hall and YMCA buildings have been nothing but white elephants to the community.

“The whole area has been a headache to us.”

He acknowledged the buildings “had architectural merits” but said “that should not be allowed to stand in the way of progress”.

Roderick Maclean, the executive director of Murrayfield, said they thought they’d need to retain a granite facing on the Music Hall, but the iconic granite pillars and steps “would almost certainly have to be removed”.

Murrayfield wanted to incorporate the venue as part of a “giant development” of modern shopping facilities, offices, a concert hall and car park.

Councillor Sutherland – the architect behind many of Aberdeen’s Art Deco buildings – was keen for progress.

All for the redevelopment of the site, he felt Aberdeen had outgrown the Music Hall, that it was too small, and went as far to say: “The place is a morgue. Inside it is a mess – awkward and wasteful.”

Georgian heritage

Murrayfield had already acquired the Royal Northern Club, formerly Crimonmogate House, at 204 Union Street.

Another attractive Georgian building designed by Archibald Simpson, it was a town residence for Patrick Milne of the prestigious Crimonmogate estate near Lonmay.

From the 1870s it became home to the Royal Northern Club, a society for landed gentry and military officers.

After the Second World War, the building changed hands several times.

In 1947 plans were mooted to turn it into a bank, in 1959 it was resold to be transformed into dance hall, garage and filling station, but it remained empty.

The Victorian YMCA next door, a building still very much in use, proved harder to purchase and the developers had to provide new premises for the club.

They were creeping closer to their goal of demolishing the whole block between Huntly Street and South Silver Street – and the Music Hall.

But a surprise intervention from the Scottish Secretary in January 1962 put the brakes on the extreme scheme.

The Music Hall must go

The powerful and formidable Secretary of State for Scotland in Harold Macmillan’s government, John (Jack) Maclay, felt the Music Hall had architectural merit.

He told Aberdeen Town Council they must have his permission before any alterations were made to the then 140-year-old building.

Mr Maclay wanted it made a category A-listed structure, which recognises buildings “of national or international importance, either architectural or historic or fine little-altered examples of some particular period, style or building type”.

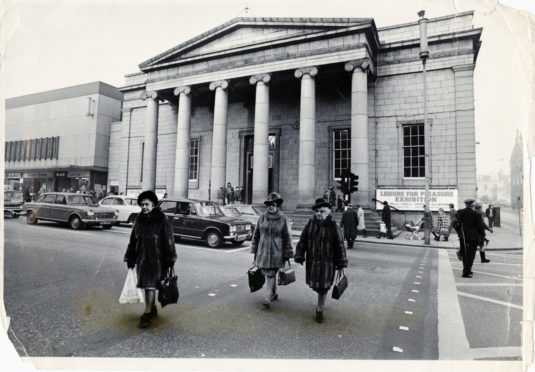

On February 28 1962, the Music Hall became an A-listed building, making potential changes more challenging.

But Councillor Milton retorted that “the council had never had occasion before to ask Mr Maclay for permission to demolish a category A building”.

He added: “I don’t think it’s an insuperable obstacle.”

In fact he went as far to say it was the will of Aberdonians.

“The general view of the people of Aberdeen is in favour of the demolition of the facade of the building at least and the removal of the steps in front of it”, he said.

“It will be many years before Aberdeen loses its character, if it ever will be lost, and I don’t expect it ever will be.

“But just as the horse and gig had to go to make way for motor transport, so must out-of-date buildings go.

“I have a sentimental interest, naturally, in the Music Hall, but I accept the fact it must go.”

City ‘selling out its heritage’

But not all Aberdonians agreed.

In fact a growing band of critics and city academics were publicly condemning what they called the “chrome and plastic facelift” on Aberdeen’s Granite Mile.

Ian Fleming, head of Gray’s School of Art, and members of Robert Gordon’s Technical College said many others were “seriously disturbed” by the plans for the Music Hall and Royal Northern Club.

The campaigners said: “These fine old buildings give grace and dignity to Union Street, a dignity which still survives in the face of tawdry facades of plastic, chromium and hideous mosaic creeping over it like a disease.

“The town council ought to think well before it succumbs to catch-penny proposals of ‘development’ and sells out its heritage to men who care for nothing but their own gain.

“It would be a dreadful bit of vandalism if these two buildings were pulled down.”

While Nan Shepherd, Scottish writer and chairwoman of the Aberdeen branch of the Saltire Society, said she would be sad to see the frontage of the club building lost.

And that the society felt the “whole facade from Huntly Street to South Silver Street was dignified and well-balanced”.

The views were echoed by the Amalgamated Society of Woodworkers who put forward a motion to Aberdeen Trades Council to formally oppose plans to demolish the Music Hall.

As woodworkers, they said they had a “special interest in seeing that Aberdeen’s old and interesting buildings are not removed” and felt the interior could be modernised but the building did not need pulled down.

Not for sale

By February 1963 the Union Street demolition had begun.

Murrayfield announced that negotiations had concluded on the Royal Northern Club, YMCA and other buildings between Huntly Street and the Music Hall.

Director Mr Maclean said they had no choice but to flatten the buildings as they had been rendered uninhabitable by vandals and were a danger to the public.

The wrecking ball was brought in and the firm hoped the £200,000 scheme would be completed by 1965.

Billed as the first comprehensive redevelopment of the city, the firm said the buildings had been designed to “blend into their surroundings”.

The scheme saw shops and offices built nearby, but crucially, the Music Hall was not touched as part of the plans.

After the campaigners’ backlash and “bitter controversy in the council chamber” about the “merits and demerits” of the venue, the council decided it was not for sale.

The council instead decided to task their own officials on deciding how best the hall could be retained and improved.

Today the Music Hall stands proud, and stands out against the hallmarks the 1960s left on Union Street.

And after an award-winning £9 million refurbishment, which was completed in 2018, the historic and much-loved building will continue to provide a cultural heart in Aberdeen.

See more like this: