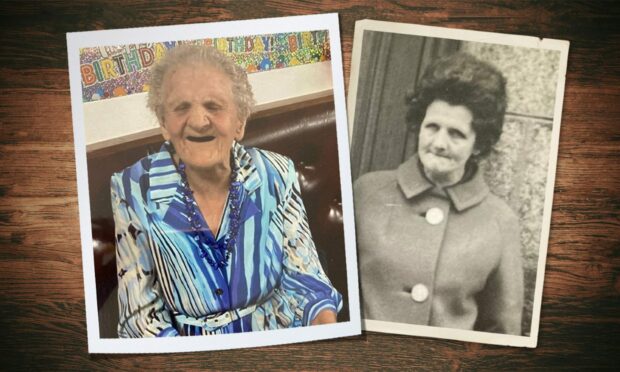

Losing her sight at 30 never held 101-year-old Rebecca Stewart back. The tenacious mother-of-six learned to swim in her 60s, partied just weeks before she died and spent decades raising money for charity.

“She didn’t want to die. More than 100 years old, living a full life… she was a very fulfilled, happy lady,” said Jean, Rebecca’s daughter.

Hardworking childhood

Rebecca Stewart – also known as Ruby – was born Rebecca Isabel Porter, in Drumbane Village, County Tyrone, Northern Ireland, on June 20, 1921.

Her father, Matthew Porter was a farm labourer, which provided the family with a cottage. Her mother Isabel suffered from bad asthma and died in her 30s.

Rebecca was the oldest of six children. She went to school in Clare, carrying a square of peat the entire five-mile walk to her classroom. Her contribution would be burned for heat; a reciprocal arrangement to pay for her education.

School finished for Rebecca around the age of 14 when she worked full-time looking after her siblings and cutting peat on the farm. However, when her dad got remarried she decided to leave home.

She took work wherever she could find it turning her hand to hotel work in Lisburn.

‘Hey red…’

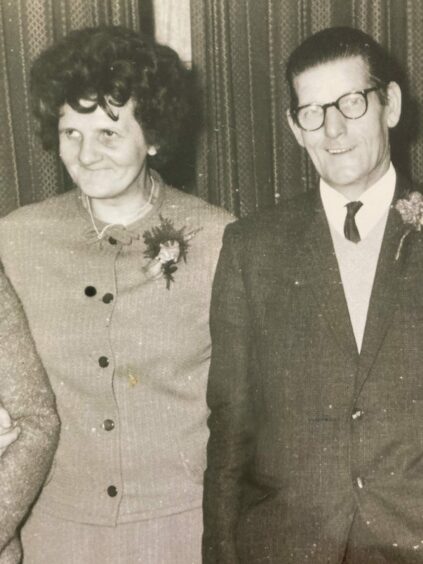

Aberdonian Fred Stewart was in The Royal Pioneer Corps, a British Army combatant corps used for light engineering tasks.

Stationed in Northern Ireland during his National Service a young Rebecca caught his eye.

With striking red hair, Fred – from Seaton – was smitten immediately.

“Mum would tell us stories of the soldiers saying ‘Hey red…’ – but it was my dad that she liked,” said daughter Freda.

The young couple married on January 6 1942 – but only after they had forged their parents’ signature because they weren’t quite 21 and needed permission.

They tied the knot in Lisburn Parish Cathedral – a protestant church.

Return to Aberdeen

Fred was soon stationed in England so Rebecca went with him, but she stayed in the UK when he was sent to Germany, working in the war office at the NAAFI.

After his posting to Germany Rebecca fell pregnant. They were living near the New Forrest so when Fred left the army the pair moved back to his home in Aberdeen.

Rebecca’s mother-in-law Jean was a comb maker, and Freddy, Fred’s dad, was a saw doctor. They had 14 children, although three died in infancy from whooping cough.

The young couple moved in with Fred’s family, sharing bunk beds in the front room.

However, a neighbour, sympathetic to their situation, offered them a room in her house instead.

Losing her sight

After the war, there was a housing shortage so Rebecca, Fred, Freda and then Jean were moved into shared prefabricated homes at Hayton Camp.

Jean said: “They had a quarter of one house with a heat source in the middle. Shared with three other families. It wasn’t an easy situation.”

But nor was Rebecca’s worsening eyesight. Diagnosed with retinitis pigmentosa she had begun to lose her sight at 18 but by the time she was 30 she couldn’t see at all.

Never held her back

As the family grew – adding Isabel, Marlene, Freddy and Dennis to their number, the Stewarts moved to Ferrier Crescent.

Opting for all home births supported by friends and neighbours, because you had to pay to get the doctor to come out, Rebecca’s family was her focus.

However, when Freddy was born with his chord around his neck, resulting in brain damage, Dennis was the only one born in hospital after that.

“I remember we all got put out in the lobby every time. Then we were all allowed back in to look at the baby,” said Freda.

‘We’d forget she was blind’

Fred worked as a labourer in the building trade while Rebecca ran their home.

Adjustments like having no coffee table on the floor and Rebecca memorising where everything was meant she learned to carry on despite her disability.

“You never knew mum was blind. We would forget to tell people actually and if you brought someone home they’d say ‘why didn’t you tell me your mum can’t see?’ And we’d have to say we forgot,” said daughter Marlene.

Living in Ferrier Crescent was a great source of community and support for Rebecca – who only ever saw her first baby.

But in 1979 the family moved to a new home in Marquis Drive. Later that same year Fred passed away.

Determined to keep going

Following Fred’s death, Rebecca embraced the changing season in her life. Rather than letting her world become smaller, she continued to find new ways to experience life more fully.

She attended guide dog training in Forfar which brought her first dog Dee and then Millie into her life.

Rebecca also began supporting Grampian Society for the Blind, now North East Sensory Services, and made full use of their gym on John Street.

If she wasn’t out on the streets near Asda, Bridge of Dee or Marks and Spencer in town, she was using the rowing machine at the gym, attending keep fit classes or learning to swim.

‘She embraced everything’

Rebecca also loved dominoes, she visited Ireland with Freda, where she met her sister Peggy, and especially loved trips out and about around Aberdeen.

“She liked going to Duthie Park because she could remember colours she would ask us to describe the flowers. She loved that.

“Mum also taught herself to swim using a rope by the side of the pool. She just embraced everything,” said Marlene.

Wednesdays were also an important day of the week for the centenarian. She and best friend Margaret would pour themselves a wee brandy and listen to Foster and Allen all afternoon.

Happy 101st birthday

On June 20 Rebecca celebrated her 101st birthday surrounded by friends and family.

“My mum just loved being the centre of attention. We went for tea recently at the Northern Hotel and had all the workmen who were there gathered around her asking her questions about being more than 100 years old.

“Can you imagine all the changes she’s seen over the years, and all the challenges… and still she really didn’t want to die.”

Rebecca passed away earlier this month following cancer.

Her funeral raised £400 for two charities close to her heart: Talking Books For the Blind and Torch Fellowship.

She is survived by her six children, 15 grandchildren, 24 great-grandchildren and two great-great grandkids.

Conversation