If there’s a more intriguing inscription on any of Aberdeen’s many memorial benches we’re yet to find it.

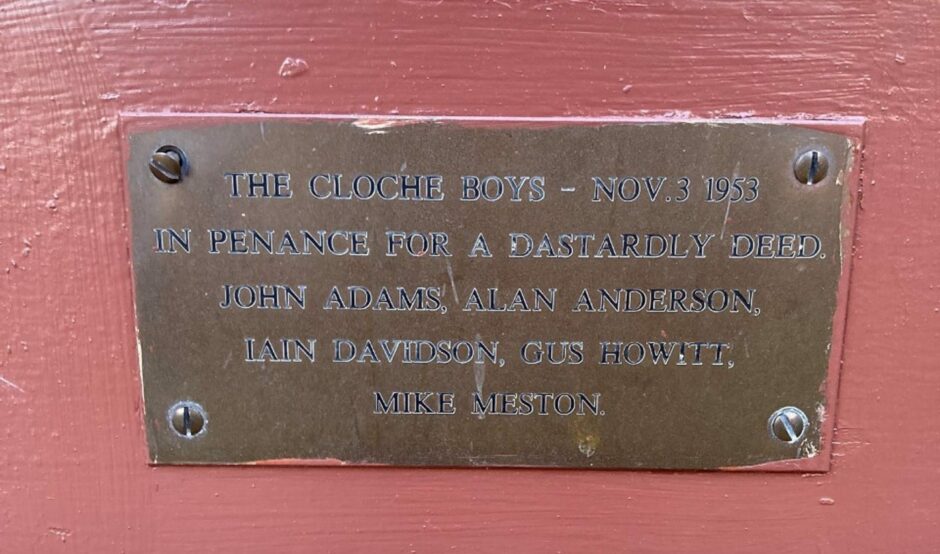

In the grounds of Aberdeen University’s King’s Quadrangle a single wooden bench carries these mysterious words: “The Cloche Boys – Nov 3, 1953 in penance for a dastardly deed,” followed by the names John Adams, Alan Anderson, Iain Davidson, Gus Howitt, Mike Meston.

Tipped off about this perplexing plaque by a reader of our A Place to Remember series, they don’t come more inscrutable this one.

We had to investigate.

The curious tale

By delving into Press and Journal archives, Aberdeen University Special Collections and by tracking down the son of one of those named, we’ve unearthed a story to rival the stealing of the Stone of Destiny.

It all took place under the veil of darkness, in 1953 when five Aberdeen students devised a cunning plan to remove the bell from their university library.

Despite the many theories that abounded at the time, it was actually a blend of student tomfoolery and pay back for “the very sour old man who used to be on night watch”.

Believing that he took “some sort of pleasure” out of making an horrendous noise in the crucial last minutes of each evening’s study time, a plot was hatched.

But it would be almost half a century before the culprits – who were simply known as the Cloche Boys – coming from the French for bell – would be identified.

The idea

In a transcript from an interview given to the university in 2000, three of the Cloche Boys revealed the story behind the bell theft.

Alan Anderson began. He said: “It was October 1953, and term had not long started. After a year in Göttingen I was still a bit unsettled and viewing an exam-less junior honours year with little enthusiasm. In this mood I bumped into Iain Davidson and John Adams, both into final year history and both similarly disaffected.”

At this point Anderson said: “Let’s do something.”

They wandered into the library, saw the bell and decided to take it.

He added: “I could borrow a cousin’s car. We would need a driver, so Gus Howitt was recruited. We would need publicity. Mike Meston’s father was deputy editor of the Press and Journal. Mike was recruited.”

The ‘dastardly deed’

Their machinations evolved and on Tuesday November 3 – a dry night – Anderson attended the Union’s German club.

It finished at 9pm giving him time to drive to King’s and park outside where Howitt collected the car. He then went into the library where he met with Davidson and Adams.

From there, Adams and Anderson climbed a staircase that led to a window on the roof. They climbed out and bolted the window behind them.

Shortly after – around 9.40pm – the bell was rung.

Davidson hid behind the bookstacks in the modern languages bay until the library had been checked by the night watchman.

Anderson said: “He then let us in off the roof and we went down to collect the bell which stood half way along the floor of the library to the left side. We muffled the clapper and Addie and I picked it up and followed Iain.”

The getaway

The bell hung on a wooden frame about “five feet by three feet”.

While they navigated their way out of the darkened building and through the office of Dr Douglas Simpson, the librarian, Meston kept watch.

When they got the all clear – in the form of Meston flashing a signal – they came out into the tower, then the Quad and down to the playing fields.

“We crossed the corner of the field to the wall alongside Regent Walk behind which Gus was parked. The bell was over the wall and into the car with Gus, Iain, Addie and myself and away. Mike was astride his motorbike,” said Anderson.

Next was a secret meeting with Aberdeen Journals.

The press man

In an isolated quarry “somewhere across the Don” the tricksters leaked the story to the papers.

Mike Meston said: “The fact that my father happened to be deputy editor of the P&J and happened to speak to a photographer, who happened to turn up somewhere near Persley… passing by at the appropriate time… a happy coincidence.”

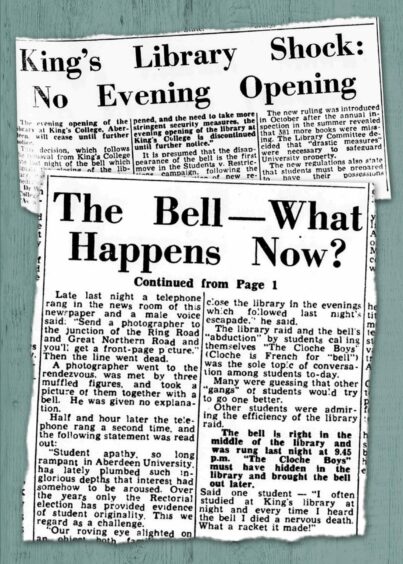

The story made page one of the Evening Express – although the reason offered for why it happened was also a rouse.

Dr Simpson also believed it was a reaction to new restrictions imposed on students rather than a heist to brighten the mood.

With the final stage of their subterfuge in action they drove to the home of Davidson who stored the bell in his parents’ coal cellar.

The accomplice

There were immediate repercussions. The library was to remain closed in the evenings.

While the “vast majority found it amusing” some other students were upset by the disruption so the Aberdeen five decided to put the bell back as soon as possible.

Davidson explained: “It was in my mother’s coal cellar. On the Friday afternoon, Gus Howitt had arranged with a taxi driver from a firm he occasionally drove with, to return it.

“Alan [Anderson] took it out of the cellar and up our tenement stairs and into the taxi.”

When the cab arrived at King’s, he parked outside, strolled in, and said: “I’ve got a bell for you.”

“I think his [the university sacrist] eyes popped out. But he did ask where it came from. ‘Oh I dinna ken, just twa lads gave me some money.’

“We did give him a big tip. It wasn’t knocked or damaged or anything,” said Davidson.

The secret kept

The bell was never used again after that – and remains in the University’s Special Collections within Marischal College today.

The five friends then donated a bench to the university in 1995 for the quincentenary year celebrations. The original plaque carried an error and on replacing it they decided to reveal their names.

It was only in 2000 that they shared the story with even close friends and family.

The ‘perfect crime’

Donald Meston, Mike’s son, said: “My dad was very evasive about it. Not to mention the fact my grandfather had sat on the story for decades too.

“Not a total surprise, given my dad went on to be a law professor, that they kept it quiet.”

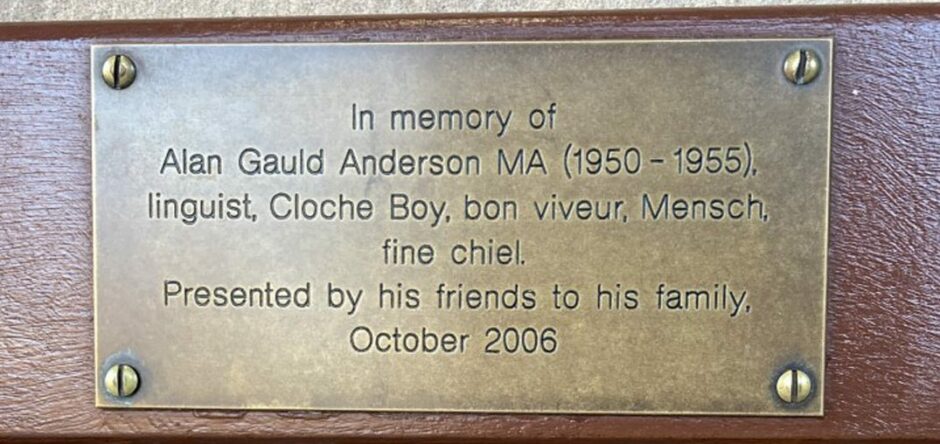

As far as our research shows, all five Cloche Boys are now believed to be deceased.

In the transcripts Davidson confessed that he hadn’t told a soul about them being behind the “dastardly deed” for 30 years.

To which the university interviewer replied: “The perfect crime.”

Conversation