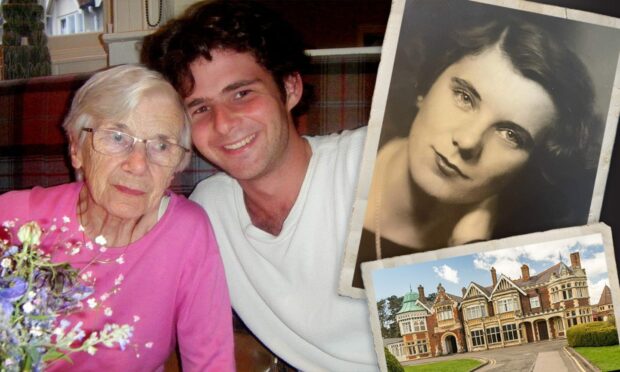

The grandson of Margaret Macfarlane, one of the last remaining members of the Bletchley Park code breakers, has paid tribute to his “5ft powerhouse granny” who died just weeks from her 103rd birthday.

The daughter of a farm hand from Old Deer kept her involvement with breaking code on the Enigma machine a secret for decades.

Humble beginnings

Isobel Margaret Law was born on August 19 1920 in Old Deer, one of four children for Jane Law and her husband James, a worker on a farm breeding Clydesdale horses.

Despite a childhood of poverty Margaret, as she was always known, showed academic promise from a very young age. Awarded a full scholarship to attend a private school in Aberdeen, she could not attend due to the cost of the uniform so, at 16, she went out to work.

Securing a secretarial job working with the son of Sir Alexander Lyon, it was always a source of pride for Margaret and her family that a girl with her start in life had earned such a good job.

Called to the war

After six years Margaret received a letter inviting her to sit an exam in Edinburgh. It was thought her employer, knowing how intelligent she was, had suggested his young secretary may be suitable for war service.

Her first time outside of Aberdeen, she scored highly in the Edinburgh exam. She was then instructed to take the train to Buckinghamshire, without explanation. What followed was an appointment at Bletchley Park with the code breakers.

Bletchley Park

Housed with a family in the Buckinghamshire countryside, she couldn’t tell her hosts what she did each day. Every morning she would disappear on her bike, and cycle back late at night. Although the days were long, Margaret loved mixing with people from all walks of life, brought together under exceptional circumstances.

As part of the Bletchley Park team she worked seven days a week in Hut Six. The hut responsible for cracking German codes from the Wehrmacht and the Luftwaffe, it was run by Cambridge mathematician Gordon Welchman.

One of the four initial recruits to Bletchley Park along with Alan Turing, Welchman oversaw the work that took place in the 18 by 9 metre-long hut comprising two rooms and no toilets.

Margaret directly used the Enigma machine – an extremely complex device reserved for skilled operators only.

The machine contained a series of interchangeable rotors, which turned every time a key was pressed to keep the cipher changing continuously. Margaret worked as part of a team operating the machines to translate coded German messages into decipherable English.

Defining moments

Until the 1970s no-one in Margaret’s life knew of her work at Bletchley Park. Having signed the Official Secrets Act it was only when books and films about Bletchley began to be released that she finally broke her silence.

Jamie Macfarlane, Margaret’s grandson believes her time in Buckinghamshire was definitive.

“My grandmother had an incredible sense of duty, and lived with an ethos of hard work and the importance of her contribution for the rest of her life. Her time at Bletchley also opened up a world of possibilities for her, however. She had a drive to experience new things, new people and new places… it was a world away from how she started in life. She was in every sense my hero.”

Falling in love

After Bletchley Park Margaret was sent to Berlin by the Foreign and Commonwealth Office to work as a private secretary to the government of the British occupied zone of Berlin.

There she met James Ferguson Macfarlane, a young Scottish soldier from Tarbert, Argyll. James, who had served in The Black Watch, had fought at Dunkirk, El Alamen, Normandy and southern Italy. However, he faced one more battle with Margaret.

The young woman, who had come to value her new found freedom, wasn’t too keen on settling down.

“She made him work hard,” said Jamie. “Grandfather was posted to Rhodesia and longed for her to be his wife. He wrote to her regularly but it was only on a return visit when she met him in Portsmouth that she agreed.”

The couple married at John Knox’s Church, Mounthooly on 10 March 1952.

Zambian adventure

Margaret joined James, who was working in Northern Rhodesia – now Zambia – initially in the tiny town of Monze with the grain marketing board.

Their first son Bruce was born there but later, following a promotion for James, the family moved to Lusaka where their second son Neil was born.

In Lusaka Margaret found work as the private secretary to the UK colonial minister of transport and works. She held this post for 10 years and was then retained as private secretary to the first Zambian minister of the same department after independence in 1964.

When she left in 1967 the Zambian Minister wrote her a letter.

“Mrs Macfarlane proved to be an excellent secretary, unperturbed when the pressure was greatest; meticulously efficient at all times, willing to ensure that the office was always on top of the job irrespective of the time involved.” He added that “much of the success of the minister during that period was due to her knowledge and efficiency”.

Ghana to Iran

From Zambia the family moved to Ghana. James worked for the United Nations as an adviser to the government on agriculture.

During this time James developed lung cancer and later a brain tumour. Margaret stopped working to look after James, who knew he must work one more year in order to qualify for a UN pension to support his wife.

With this in mind he took a job in Iran with UN Food and Agricultural Organisation. Margaret was based in Tehran enjoying Iranian life, and also taking the opportunity to travel across the country.

Her long held belief that “Scots are the reason the Empire worked” remained intact the more of the world she experienced.

Glasgow bound

When James’ health further deteriorated they returned to Scotland setting up home in Bruce Road, Glasgow.

On March 9 1977 James died aged 59. Margaret remained there until 1994.

Her lifelong mantra “it’s all grist to the mill” was lived in her new season of life as a widow. She made use of her time travelling the world to visit her sons in New York and the Middle East, studying with the Open University and taking cordon bleu cookery courses.

In her later years she moved to Kensington to be near her family.

Sharp minded

Watching Newsnight with a whisky, and devouring The Times each day, purchased – at her insistence – by a coupon were regular activities. As was maintaining a diet of hearty Scottish fayre.

For her 90th birthday Margaret’s family took her back to Bletchley Park. A special celebration took place where she was reunited with former colleagues.

“For her entire life my granny had a deep humility. Even there at Bletchley it wasn’t about her, it was about the place ‘where we won the war’.

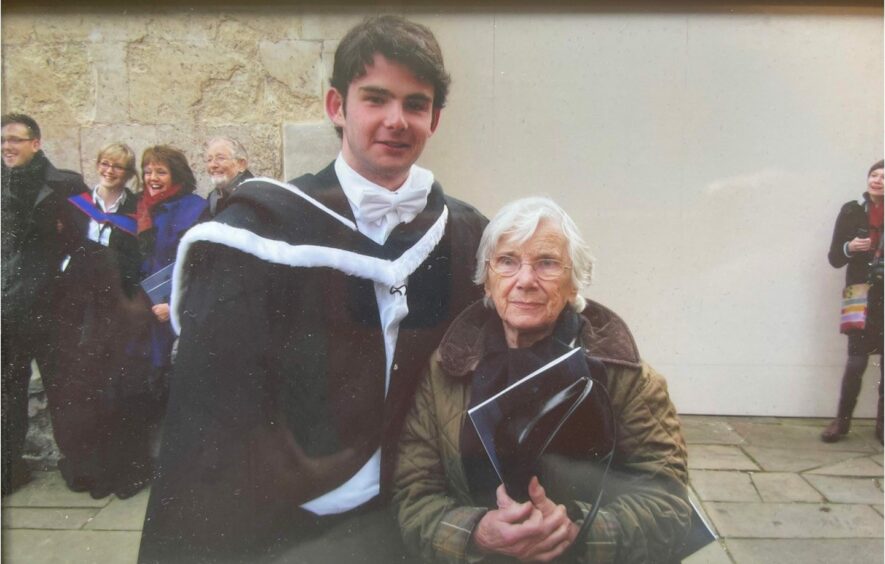

“She was amazing. She made the most of every second of her life, and never lost that zest to learn,” added Jamie. “When I got into Oxford that was really meaningful for her and she loved visiting me there.”

Final act of honour

On July 20, just one month from her 103rd birthday, Margaret died at home with her son by her side.

“For as long as I can remember, whenever I left her home she would stand at the window and watch me go,” said Jamie.

“The morning after she died, the undertaker came to take her away. Me and my dad just stood at the window and watched as she was driven away. It was the one last act I could do to honour my granny. The 5ft powerhouse, who to her last day was a proud Aberdonian.

“She will forever be an inspiration to us all.”

She is survived by her sons and their wives Maggie and Susan, and her grandsons, Jamie, Joshua, Toby, Angus and Hugh Macfarlane.

Conversation