Eòghann Vetch Maclachlainn, of Tobermory and South Uist, lived an extraordinary life but was most at home on his croft, where he died peacefully on February 10.

He was 91 and died less than a day before his equally inspirational older sister, Morag Fraser—a nursing sister and matron at Belford Hospital.

Eòghann, pronounced “A One,” as he liked to tell people who struggled with Gaelic, was well-known throughout the islands and beyond.

He would say about himself, “Is mise Muileach, and I can never be anything else.”

He was known to many as The Muileach.

To many, he was a schoolteacher, taking up his first position at Tobermory as the maths and science master before relocating with his family from the beloved generations-old family home of Bad Daraich in Tobermory to set up a new home in South Uist.

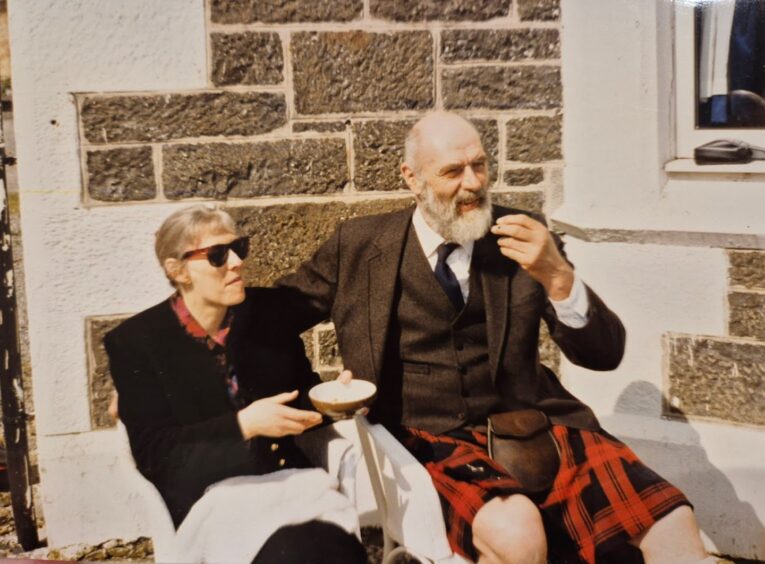

He loved to talk, and he loved his garden, which he described as “paradise.”

He was a veteran, a scout leader, a formidable gardener and believed strongly in Scottish independence.

War-wounded veteran, scout leader and gardener

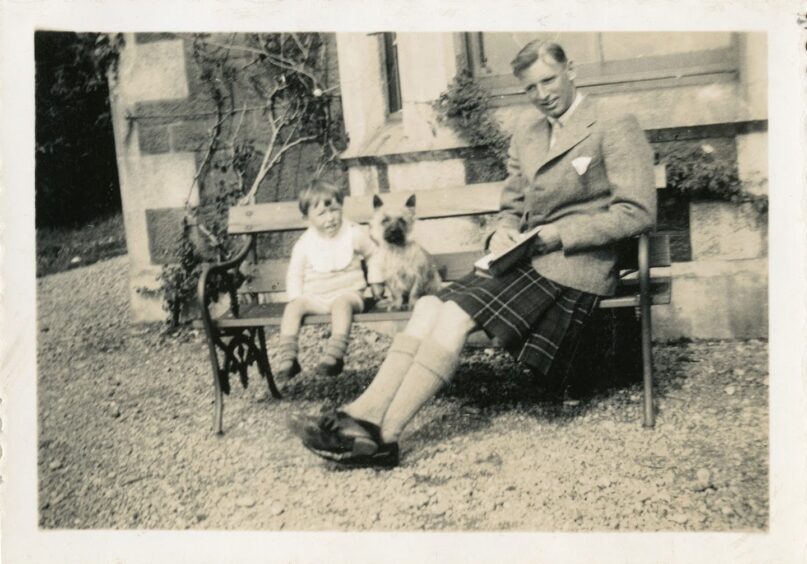

Eòghann grew up on Mull and loved his life there.

As a boy, he was known for climbing trees with his friend Campbell Lamont.

At the time, Eòghann ‘s dad was at war and then a medic on the whaling fleet in South Georgia during his childhood, so was rarely at home.

During World War Two his father would write to them in the ancient alphabet of Ogham before translating it into Gaelic, then English.

When it came time for high school, Eòghann’s parents insisted he be sent to boarding school—something The Muileach hated and never quite got over.

He vowed that his own children would never be sent away to school.

He never gave up his Tobermory accent, despite being teased for it by classmates at George Watson’s College in Edinburgh.

During long summer holidays, he spent many happy days with a local haulier Duncan MacKinnon who, with his wife Netta, became like family to Eòghann.

He loved this work and would have chosen it as a career because it allowed him to talk to people all day. Eòghann loved people.

After school, he reluctantly attended Edinburgh University to study maths and science.

Eòghann was ‘pummelled’ during a boxing competition

One of his proudest achievements was finishing second in the inter-university heavyweight boxing challenge.

At 6’4″, he was a big man, but he knew that two other universities had been unable to field a contestant, which meant he had a real shot at a medal.

He was “pummelled” during the competition and was “terrified”—but absolutely delighted at his title.

Eòghann met his future wife Sheila at a party in Edinburgh in 1959.

Sheila, née Cessford, who has survived her husband of 65 years, was rescued from Singapore as a child and flew on the 2nd last seaplane flight before the Japanese took over the nation during World War Two.

She was a nurse in Edinburgh when she met Eòghann.

They were introduced by a fellow nurse, Mary Henderson, who was from Mull.

She warned Sheila not to get involved with Eòghann, as he was reputed to have “girlfriends everywhere.”

‘I am getting married’

After meeting Sheila, Eòghann wrote to all his girlfriends, wishing them well but telling them he was getting married. They were married in Glasgow in 1960.

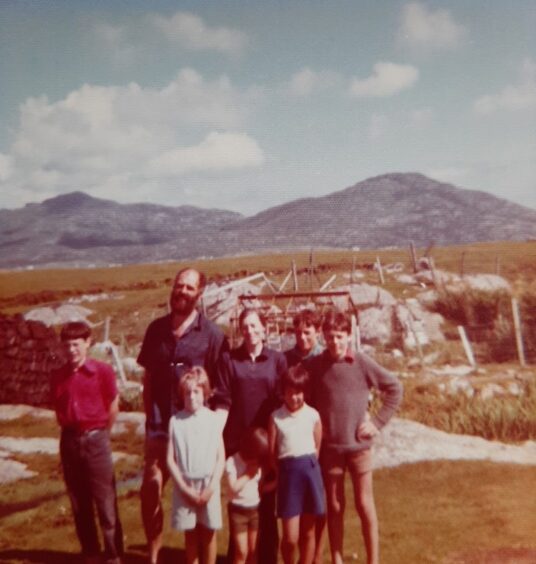

The couple had six children: Dughall, Domhnall, Calum, and Susan before moving to South Uist.

Anna and Seonaig were born in South Uist at Daliburgh.

Eòghann served his National Service with the 300 Squadron airborne engineers in the Territorial Army, rising to the rank of captain.

Although he detested war, he loved the camaraderie and the high jinks of army life.

In April 1965, he was sent to Aden in his role as a captain in 300 Squadron/ 131 Parachute Engineer Regiment.

While in Yemen, his troop was ambushed, and two men were killed.

Eòghann was shot in the head—the bullet narrowly missed his brain and exited through his jaw.

Four others were seriously injured.

For the rest of his life, he grew a full beard to cover the injury and the disfigurement it left behind.

Eòghann recognised for military service

Captain Maclachlainn received the General Service Medal medal with a South Africa clasp, but only in 2018 after his then MP Angus Brendan MacNeil intervened.

In 1966, the move from Mull where his ancestors had lived for hundreds of years was not a decision made lightly.

But his desire for his children to speak Gaelic, the recent wounding in Aden, his love for ponies and most of all his desire to live in a crofting community were factors in the move.

He used a local fishing boat instead of hiring a Pickfords van to do the move “like any normal family.”

The Maclachlainns moved using the Gibson’s boat from Tobermory to Lochboisdale, with Eòghann in his combat jacket directing the move from the pier.

Eòghann was determined to have his own croft and make his own life with his family of six children.

He became the teacher of maths and science in Daliburgh but his real love was taking pupils out of school to teach about plants, agriculture, island life, canoeing, swimming and sailing.

A case was made for the council to pay for hay

In 1970 the family moved from a rented property to their croft in South Uist, all eight of them shared a one-bedroom caravan for almost six years while their house was made habitable.

There were no facilities, no electricity, and no sanitation.

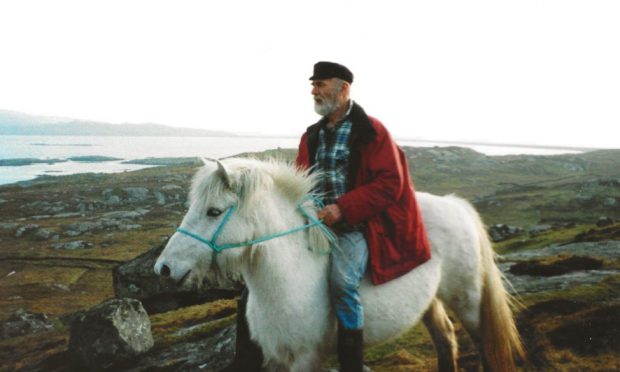

With no public road and a two-mile walk to the roadside, Eòghann had his children bareback ride Eriskay ponies to school in all weathers.

He even wrote to the council, demanding they pay for hay for the ponies. He argued other children had their school transport covered. Naturally, he won the fight.

The children set off early each morning. They became known across the country for their unusual school transport.

Midnight calls to friends

His children say he fought for people, especially those who had a difficult start in life.

He loved beekeeping and botany and eagerly shared his knowledge with anyone who showed interest.

He loved language and Gaelic.

Most days, he wore his kilt with pride.

When told he couldn’t plant trees on South Uist, he did it anyway, later sharing homegrown apples and an abundance of strawberries with friends and neighbours.

He was renowned for making midnight calls to friends, whether on the phone or in person. He stayed up talking into the early hours.

Eòghann always said he wanted to die at home on his croft, near his beloved garden.

And he did—his croft house still unfinished, but his garden thriving with abundant life.

Many will miss his voice, his joy of life, and his ability to see the best in everyone.

Have you signed up for our Oban and Hebrides newsletter?

Sign up here for local news straight to your inbox, and join in the conversation on our dedicated Facebook page.

Conversation