How is it possible to hear when so much noise is happening all around us? This is one of the biggest problems of our age.

The noise I’m talking about is both literal and metaphorical. We live in the midst of a Babel of perpetual stress-inducing racket.

For starters, we are deafened by high decibels from open car windows, from bands with the volume turned up to ear-bursting levels, and from bellowing mouths.

But the noise I’m talking about also comes through CAPITAL LETTERS on social media, as wild and often platitudinous ‘certainties’ are spouted forth in migraine-inducing quantities.

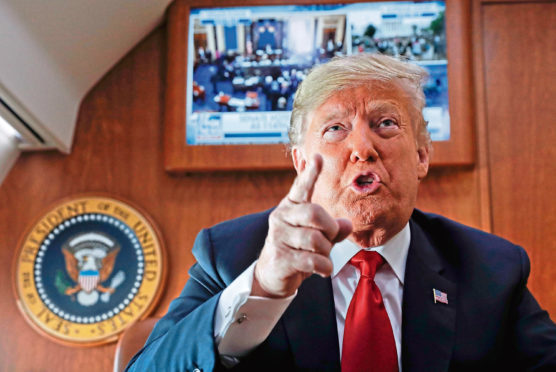

The alleged leader of the free world in the White House is the culprit-in-chief. SO SAD!!

Oppressive noise is not entirely new, of course, but today’s pervasive din has a distinctive and often deeply unpleasant edge to it.

Belligerent bores dominate the airwaves and the social media spaces. They routinely describe people who dare to disagree with their views as “roadkill”. Charming.

They body-shame vulnerable youngsters and, in extreme cases, advise them to commit suicide. In America, such poisonous attacks are characterised as “drive-by shootings”.

Staying with the deeply divided Land of the Free, the sheer vitriol poured out during the Supreme Court nomination hearings was an American disgrace.

The misogyny on display was truly staggering. Neither Democrats nor Republicans came out smelling of roses.

And Brexit?

How did we come to this snarling pass? When did Britain become addicted to noisy abuse?

Writer William Leith talks about a revealing incident a few years ago. He flagged down a taxi in the middle of London and got in. As he closed the door, another man got in the taxi on the other side.

Leith instructed the taxi driver, “Camden please”. The other guy said, “Clapton”.

“Hey,” said Leith, “I got in first”. The other man shouted abuse at him.

The driver told them to sort it out themselves.

“Get out or I’ll smash your face in,” Leith was told.

Leith concluded: “At the time, it occurred to me that something bad was happening to the world around me”.

Quite.

Allow me to return to my original question: How is it possible to hear when so much noise is happening all around us?

I’m not sure of the answer to this question myself, but I do feel strongly that the poisonous atmosphere in which current issues are discussed, allied to the manic pace of modern life, is driving us, as a society, mad. All this discordant, uncivil noise is not unrelated to the current rise in mental health problems, especially among young people. (While we do need more trained practitioners, it is unrealistic to think that more staff will solve the crisis we face).

We do need to quieten the noise, in order to think straight.

What is it about silence that is so threatening to us moderns? You can’t even have a meal out without piped pap playing in the background.

Apparently classical muzak makes us “think rich”. Ah well, it’s reassuring to know that Bach has his uses.

“So does our progress make commercial travellers of us all, and take away the primeval joy in sun, in wind, in divine idleness,” said that great Scot, RB Cunninghame Graham.

Now readers may be thinking that I’m going to present the Christian Church as the answer. Well, I’m not.

The Church, at its best, preserves and promotes a contemplative way of life. But it’s not at its best.

Silence can be hard to come by, even in church services. Babel rules. Cheerful chatter is everywhere, even while – especially while – the ecclesiastical ocean liner lists badly and frantic bailing out is going on below.

In EM Forster’s novel, A Passage to India, Mrs Moore has come from England to India to see her son. Distressed by the British colonials’ lack of appreciation of the spiritual climate of India, she visits the caves at Marabar. Suddenly, the echo in the cave mysteriously undermines her hold on life, and in that disorientating, wobbly moment she understands that “poor little talkative Christianity” is inadequate.

The need for quiet contemplation affects not only institutional religion but society in general. The perpetual background and foreground racket is getting worse.

It’s as if there was a conspiracy to stop us all thinking. This overstimulation desensitises us and leads inescapably to spiritual brain death.

We seem to have lost our capacity for silence and for close attention to the authentic.

I am drawn back again and again to the work of my late friend, the Orcadian poet George Mackay Brown.

The words of his epitaph, carved on his gravestone at Warbeth cemetery, Stromness, with its backdrop of the majestic cliffs of Hoy, should be memorised by all:

Here is a work for poets –

Carve the runes

Then be content with silence.