Our modern relationship with sugar is a less than happy one: an obesity crisis, mounting queues for dental surgery and a tax hike attest to that.

But there was a time in Scotland’s past when there was an even less appealing aspect to it and not just for health reasons.

“Ball of suggar”, “candied bread suggar”, “pouder sugar”, “panellis sugar”, “licorish ball” and “confected candie”. These strange-sounding items were the more exclusive, tooth-decaying treats to enter the diets of the richer members of Highland and Moray society in the 1680s. This was happening two decades before the formal creation of the British Empire and these sweet delights were arriving, not from Leith or London, but from the Netherlands and, in particular, the port of Rotterdam.

Between the fall of the Lordship of the Isles in 1493 and the Battle of Culloden in 1746, the Highlands and Islands was a complex, dynamic place, governed by a range of violent, coercive and conciliatory approaches. A concept of land and society based on trusteeship that was inherited was colliding with one defined in written charters. International commerce and empire were establishing a grip.

Why write an article about Dutch plantation sugar and the Highlands, specifically?

Regarding the 1600s, I’d used the Inverness customs accounts, local estate papers and burgh records before, and the growing frequency of references to this import had caught my eye. Previous work had also shown how the Dutch provided much to the firth ports at this time.

But I then saw something which puzzled me. On corresponding with some leading scholars of the Dutch Atlantic, my attention was drawn to a digitised version of a 1667 map which showed a sugar plantation called “Scotsmen”. Perhaps this Highland engagement with Dutch imports had extended also to an entanglement in their empire? Had slavery-derived cane sugar become a sweetener, both literally and economically, for some early Highland-born agents of empire?

The map was of the then-colony of Suriname, on the north-east coast of South America, and a prize taken by the Dutch from the English that year.

Another 1667 map of Suriname, this one in the Dutch language, denoted two adjacent households in place of “Scotsmen”: “Magalfin” on the south side and “Macfarson” to the north. These looked like Dutch versions of Gaelic names, possibly from the central Highlands.

Other Highland names emerged in the documents, although the individuals remained rather obscure.

Henry MacKintosh, a Suriname sugar plantation owner, did not. I assessed the evidence that MacKintosh, from the Borlum branch of that family on Loch Ness side, relied on the blood, sweat and exploitation of those enslaved to him, in a web linking Suriname with New England, Rotterdam, and Inverness in the same decade, the 1680s.

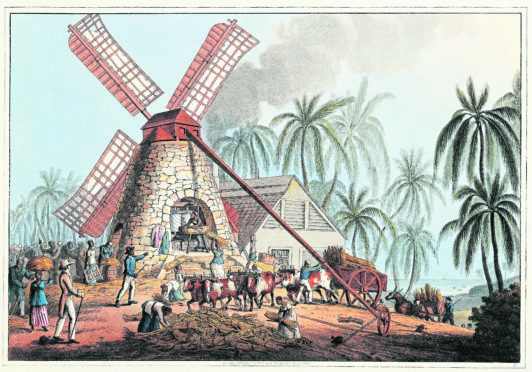

From 1674, there survives an “Agreement between Rowland Simpson and William Pringell and Henry Mackintoshe for the sale of two Plantations containing 1,600 acres of land for 600,000lb muscovado sugar”. By 1680, MacKintosh was the third largest plantation owner from the British Isles in Suriname, in terms of numbers of slaves (in his case, thirty). Four years on from that and, along with a new business partner, Englishman Samuel Lodge, he owned seventy-three slaves, seventy of them African and three indigenous people.

The diary of a Scottish visitor to Suriname, Rev. Francis Borland, highlights that, on 26 June 1687, he moved to “Mr. McIntoshe’s and Captain Lodge’s plantation in Succico”, for what would become two years of residence there.

While writing up my research, I had the chance to give a public talk in Inverness, which brought about new leads. Further reflection produced an article, recently published in the journal, Dutch Crossing, which, I hope, highlights two things. The first is that the region imported, in the decades before the Anglo-Scottish Union of 1707, sugar with origins in the empires and slave plantations of continental powers. The second, sobering point is that this Highland engagement with the Dutch Empire marks the earliest evidence found to date of an organised circle of migrants from the far north or west of Scotland enslaving African and indigenous populations in the Americas.

As for next steps, I aim to explore this Imperial seepage into the Highland and Scottish diet and economy further, as part of a developing collaborative project involving University of the Highlands and Islands colleagues working in the fields of diabetes, public health and archaeology.

Research like this does not leave a sweet taste in the mouth. Considering the horror of the sugar-based slave trade, I’ve recently felt the urge to deal, trivially perhaps, with my own ‘sweet tooth’ through eating less refined sugar, and seeking to find an alternative instead in the many fine varieties of locally-made Highland honey.

David Worthington is head of the Centre for History at the University of the Highlands and Islands