The voice on Amazon’s number one song playing in my kitchen was familiar, like a voice you knew once but had changed, grown deeper with the years and the nicotine.

“For worse or for better, we’ll always remember the tears and goodbye.”

I certainly remember his tears – Mr Bay City Roller. Les McKeown wept in an Edinburgh hotel over double bourbons. Typical of hot-then-not fame, isn’t it? He wanted one more number one, but had to die to get it.

On the surface, Les was everything I normally hated: a cocky “booze and burdz” Jack the lad, who confessed over his bourbon that when he went to posh people’s houses in his heyday, the maid had just been another person to pull. Somehow, I couldn’t dislike him.

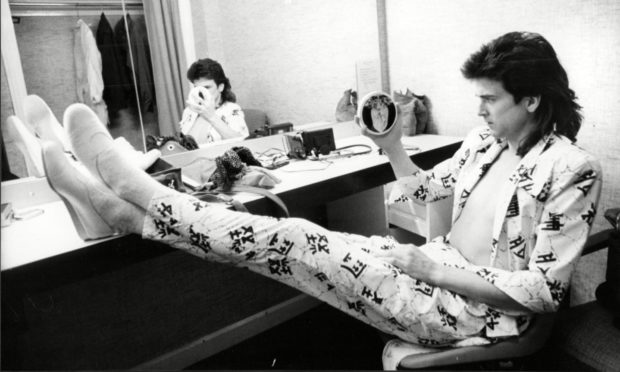

When we met for an interview, he was angry and he was bitter, yet intensely vulnerable – sad and confused with an addictive personality and a deep sense of shame about the things he had done wrong in his life. Later, the pictures showed that he had turned up to the photoshoot in a graffiti t-shirt emblazoned with the word “DAMAGED”. How apt that was.

Living the good life?

The tears in that first meeting were for his parents who had recently died, one after the other. The double loss left him disabled.

“How can your mum and dad die?” He asked. “It’s impossible.”

He had a favourite photo of them in the Cornish house he had bought them, laughing into the camera, living the good life. Les’s good life had involved long trails of coke along the mantelpiece, snaking towards the self-destruct destination where suddenly the coke wasn’t good anymore and neither was life.

After his father died, his mother, Florence, gave him a shoebox stuffed with envelopes he had given them over the years – £20,000, untouched. Florence, he said, was the most beautiful woman in the world. “The only woman who gave me a true kiss.”

What would Peko, his wife, say to that? She would understand, he said. He loved Peko but was sometimes unfaithful. Now, he was struggling. “You know that thing when you don’t want someone to be with anyone else?”

“The trouble with you, Les,” I said, “Is that you don’t want women to behave like you do.”

Constantly searching for unconditional love

“We can’t change a thing, so don’t let it hold you back.”

He struggled with that – the acrimony of the band blowouts and the resentment against manager Tam Paton who controlled with a rod of iron and who, he suspected, got the missing millions that had never come McKeown’s way.

I realised, then, what was different: it was the first time we’d met that he hadn’t cried. He’d processed something

He was terrified of Paton. Paton made sexual advances to several of the Rollers and in a later interview, Les would tell me, he had sex with him. He considered himself bisexual but it seemed like he was searching for unconditional love wherever he could get it: the true kiss.

Maybe, he speculated, his sexual drive was just a search for the intimacy of a mother’s love. “Aye, good try Les,” I said, and he laughed, that rasping, bourbon-and-nicotine laugh.

Learning to heal

“Can’t hide from the memories, I’m carrying the scar.”

His addiction cut a deep, dangerous trench through his life. We met for a TV interview after that first conversation. Afterwards, I comforted him while he cried again, and the crew wrapped up in awkward silence.

Years later, our final interview was in a London shopping centre sandwich bar. He was different that day, though I couldn’t put my finger on it.

Certainly, he had been through rehab, the double bourbons replaced with coffee. The honesty was searing; mid-sandwich, he said he had been “a sh*t husband and a sh*t father”, and when his adored son was invited into his therapy session and told Les that all he’d wanted growing up was his love and approval, he almost hit the bottle again to drown the words out.

I realised, then, what was different: it was the first time we’d met that he hadn’t cried. He’d processed something.

Learning to forgive

Fame was a fickle friend. Les McKeown tasted it and wanted more of it. Hard to believe, listening to the voice, that he had run out of time.

“If you wanna live, you gonna learn to forgive.”

I think he forgave himself in the end, and in doing so gained the forgiveness of those he loved. He had faced himself, accepted it, tried to change it. There was bravery in that.

“I just want to be a better person,” he said.

If he achieved that, perhaps it’s not quite so sad that the final number one didn’t come in his lifetime.

Catherine Deveney is an award-winning investigative journalist, novelist and television presenter