This month’s buzz term (and by “buzz” I mean an irritating omnipresent drone) is, apparently, “geriatric millennial”.

It’s yet another attempt to describe the people born between 1979 and 1985, on the cusp between two generations.

Too old for Harry Potter, too young to have really understood Gen X slackerdom, we’re the ones who got our first mobile phones and taste of internet access in our very late teens and early 20s. We have previously been referred to in the media as “Xennials”, “Cuspers” and “Generation Catalano” (after Jordan – if you don’t know you weren’t there).

It is, of course, just one more deliberately divisive construction designed to slice society up into boxes, all the better to market more stuff to us. But then, it is a natural human instinct to create common ground from shared experience.

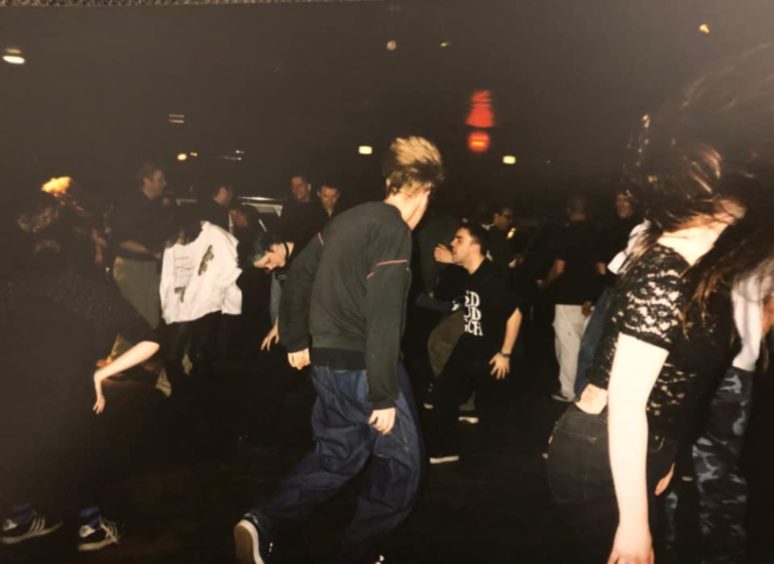

Something very specific to my “microgeneration” came flooding back quite powerfully when I visited the Night Fever exhibition at the newly reopened V&A in Dundee this week.

Night clubs are as much part of culture as theatres and opera houses

Night Fever is an interactive walk through 60 years of clubbing history, starting with the chic discos of 1960s Italy, taking you past memorabilia from Studio 54 and Paradise Garage, as well as a square cut from the dancefloor of Manchester’s legendary Hacienda. By examining clubbing as it intersects with design, architecture and fashion, the exhibition makes the case that night clubs are as much part of culture as theatres and opera houses.

Night Fever looks at how you create a club. A place designed to make its punters feel like members. Part of a tribe.

In the exhibition’s socially distanced, mirrored silent disco booth, listening to a slow-building house groove, I began to remember all those spaces my particular tribe of not-yet-geriatric millennials learned to prowl around in Aberdeen.

Before clubbing went fully commercial

Always on the cusp, us – we came of age just after the Criminal Justice Bill had herded rave culture indoors (again, you put something in a box, it’s easier to monetise it), in the era just before clubbing went fully commercial.

The venues my friends were attracted to were always the grungiest. Remember the three sticky-carpeted floors of The Palace? Pints of flat Tennent’s slopping over fists as you moshed to Nirvana on Monday nights (the Mudd Club) or struck shapes to Kelis on Thursdays (Disco 2000, as every indie night club in 1999 was legally obligated to be called).

Doing “a Palace lap” to check out the talent, we learned the architecture of that place – its assorted balconies and stairwells dropping hints to its various pasts as a cinema and bingo hall, the long squeeze against the mirrored wall that queuing for the toilets involved. The sheer amount of cigarette smoke must have meant great savings on dry ice for such a big space.

Everyone from Daft Punk to Derrick Carter played the Pelican Club, just for the sweaty joy of the atmosphere

There was Glow303 on Belmont Street, where I saw Dizzee Rascal and cut my knee open falling down the steep wooden stairs. There was Estaminet, where the KP from the cafe I worked in would DJ until the early hours, then you could pile back in there the next day for a restorative fry-up.

The Pelican Club was a whole new world

My favourite was always The Pelican Club, because getting to it felt like a grown-up version of Narnia. Instead of a wardrobe of fur coats, you had to brave the tartan decor and sherry-drunk older ladies clustered around the downstairs bar of the Rox Hotel on Market Street.

In my memory, there was a secret door behind the cigarette machine that led down stairs hewn out of rock to an all-white underground cave where everyone’s teeth shone in the UV light.

Guided initially by an older boyfriend – a Mr Tumnus who worked as a chef in the Portlethen Morrisons café – I began discovering electronic music. The Pelican Club was tiny, minging and unprepossessing and everyone from Daft Punk to Derrick Carter played there, just for the sweaty joy of the atmosphere.

This was a whole new world to me, and I spent a lot of time hanging shyly around the sidelines, trying to understand its codes and not quite belonging. However, it was a world that was already changing.

The birth of the soulless superclub

In 1998, the week I moved to Aberdeen, I turned 18, got my first email address, and visited my first “superclub”. Brand new and with a widely-publicised multimillion pound price tag, Amadeus was the largest purpose-built club in Scotland.

Amadeus is now a branch of The Range, where it is regularly visited by the geriatric millennials who hoisted themselves onto its podiums after a few Aftershocks two decades earlier

I was one of the hundreds of freshers herded onto the free buses that funnelled us out of the city, past the beach, to the retail park. Looking at old photos of it now, it was like the set of The Big Breakfast rebuilt on a massive scale, all quirkily wonky MDF walls, podiums and massive faux-luxurious chandeliers.

You went for the cheap drink, definitely not out of love for the music. A huge, soulless machine designed to part young clubbers from their money by isolating them from any other options.

The power of a shared memory

All of those clubs, individual in their own completely different ways, had closed down by 2004. In noughties Aberdeen, most city centre clubs were taken over by nationwide chains, cynically assuring a new microgeneration of punter of the same experience, no matter which branch they went to.

A victim of its own isolationism, Amadeus sat empty for almost 10 years before being turned into the beach-side branch of The Range, where it is regularly visited by the geriatric millennials who hoisted themselves onto its podiums after a few Aftershocks two decades earlier.

Right at the end of the Night Fever exhibition is a chill out room where the curators pay homage to Scottish clubbing history. There’s also an interactive display asking former clubbers to record their favourite night spots from years gone by.

I wiped down a silver pen and added a dot on the map of Aberdeen on Market Street. That’s the power of a shared memory; I can finally feel like part of that tribe.

Night Fever: Designing Club Culture runs at V&A Dundee until January 9 2022

Kirstin Innes is the author of the novels Scabby Queen and Fishnet, and co-author of the forthcoming non-fiction book Brickwork: A Biography of the Arches