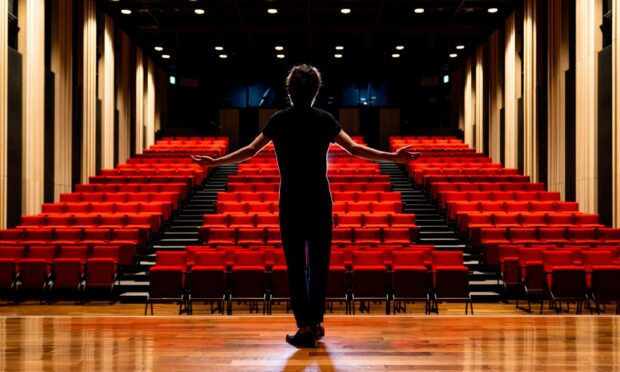

Theatre is no stranger to plague.

As early as 430 BCE, outbreaks of disease were disrupting dramas in ancient Athens. The Black Death swept the city of London in 1606, shuttering Shakespeare into a lockdown where he would labour to finish King Lear and Macbeth.

In times of crisis, it is the gathering place of the theatre which suffers. Yet, through all this, theatre remains a healing force that can help us understand the tragedies we have faced together.

It remains a powerful and incredibly resilient medium. Even in the low ebb of lockdowns, our demand for its storytelling has not changed.

Disease and drama have coexisted for thousands of years, changing with the times as each pandemic has challenged us. The same can be said for our own time of sickness, which has seen our cultural landscape pummeled by closures, companies disbanded, buildings lost and the unquantifiable human cost of lives and livelihoods.

A huge leap towards accessibility

These are still dark times. The legacy of the pandemic will be felt for decades and it is unrealistic to think that theatre can bounce back immediately.

Digital theatre gives easier cultural access for immunocompromised and disabled people, who find themselves neglected in conversations around ‘unlocking’ the sector

It is tempting to go back to business as usual, to move ahead from this time and get back to doing things exactly as we once did, but I believe this would be a huge mistake for theatre.

This is a moment for evaluating the flaws that existed with the industry before coronavirus and to move forward in a way that incorporates the hard lessons the sector has had over the past year.

Lockdown made many live events impossible; it placed a screen between actors and audiences, and that has been tough. Many of us rightly want to return to live events, and we should. Yet, we should also acknowledge that theatre has taken a huge leap towards accessibility that otherwise may have taken years to accomplish.

By necessity, we have had months of affordable digital work that overcomes many of Scotland’s existing barriers to accessing culture, such as economic accessibility and geography.

In addition, digital theatre gives easier cultural access for immunocompromised and disabled people, who find themselves neglected in conversations around “unlocking” the sector and abandoning digital work in favour of in-person performances only.

Our culture is increasingly virtual

I believe that, by forcing work online, theatre has become more accessible, less concentrated around the Central Belt and can now reach the non-theatre audiences it has previously struggled to appeal to.

Theatre has had to assert itself online and challenge the algorithm-driven heavyweights of Netflix and Amazon, with the goal of championing new stories and promoting new talent.

Yet all of these responses to Covid-19 are temporary measures. Artists and institutions reacting to an existential challenge, trying to find new ways to make work for the rest of us. The question now is: what bits of this experience will theatre keep after social distancing ends? Will there be a place for digital theatre once the elbow bumps stop and people can return to the stage in-person? I believe so.

Theatre is a place for cultural critique and, for better or worse, our culture is one that is increasingly virtual. Therefore, a post-Covid theatre must also complement its live performances with tickets for online viewing whenever affordable for theatres to do so.

Not only could this increase audience numbers, it would enable theatre makers to be ambitious in delivering online and physical work that is accessible worldwide.

We should begin to use the internet the same way theatre integrated film into live performance a century ago. It is another tool to be a part of the work.

How to stay relevant

Nothing should replace live theatre, but it is important to engage and understand audiences outside of theatre’s bubble, to realise that we endanger theatre itself if we refuse to integrate digital work going forward. Online shows must become a permanent staple of the theatre industry.

If we refuse to grow, then the industry is set for a path of increasing irrelevance, left out of an online world

This is now a question of staying relevant in a quickly changing cultural landscape.

Theatre must continue to assert itself in the context of everyday entertainment. If we refuse to grow, to realise the innovations of lockdown, then the industry is set for a path of increasing irrelevance, left out of an online world.

However, if it is successful online, then it can find new audiences and create an instantly accessible culture of creator-led projects.

Theatre must fight to become essential, but it is a fight that it can win.

Jack MacGregor is a University of the Highlands and Islands graduate and now works as a freelance as a director and writer in Inverness