As you read last week, I had spent my first two days in the Albanian south of the city of Mitrovica.

Muslim, pro-EU, pro-NATO, pro-US and UK, it all changes with a walk over the dividing bridge.

I walked the hundred feet or so, past the Kosovan police, past the NATO KFOR troops on the bridge and stepped into what felt like Russia.

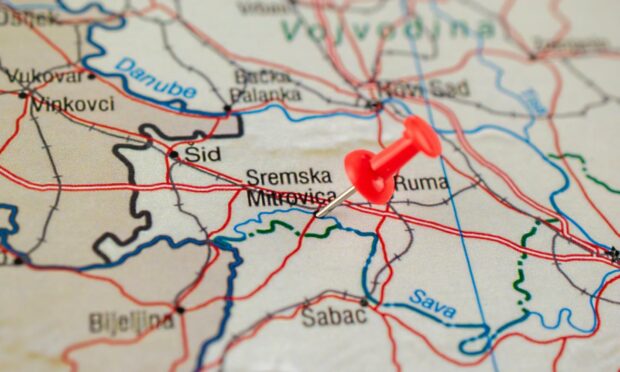

To make things even more complicated, the north of the city of Mitrovica, is known locally as North Kosovska Mitrovica.

Around 16,000 Serbs live there, and they do not accept that since 2008 they now live in independent Kosovo. They claim all of Kosovo is Serbian and their loyalty to Belgrade is absolute.

While Albanians in the south are delighted to hear you are from the UK and actually shake your hand, and some even thank you for NATO intervention during the Balkan wars, you won’t, of course, get that in the north of the city.

Any pro-western views you may have, need to be kept to yourself.

I spent two days wandering the north, always coming back to the south side before it got dark.

What’s it like, what has changed?

Well, last time, I remember the north being seriously run down. I remember it feeling like a criminal area. I remember it despondent. I remember it feeling untrusting and unwelcoming.

I have to be honest – it doesn’t look or feel as bad now. It’s better. No doubt about that. That said, I still prefer the south of the city. It just feels more open and welcoming.

The interesting thing here is that what while I most certainly do not look Albanian or Muslim, I am welcomed warmly in the south of the city.

In the north, I was also fine, due to me keeping my mouth shut and my politics to myself – never an easy thing for me to do.

No one batted an eye lid as I walked around.

Thing is, with my white skin and shaved head I can easily pass for Slavic. As I shared a chat with a cafe owner who spoke a few words of English, I observed our similar appearances.

Side by side, we looked like the Mitchell brothers from EastEnders.

The first difference that hits you when you walk over the bridge, is the Café Moct. “Moct” pronounced “most” is the Russian word for bridge. Hence, “bridge cafe”.

See photo. It was like stepping back in time, into provincial Russia in the ’90s.

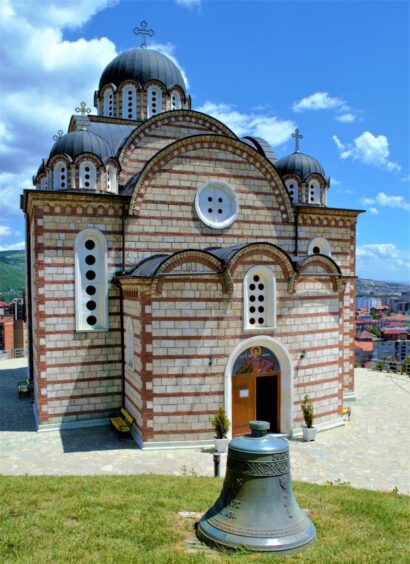

Pro-Serbian and even Russian propaganda is displayed colourfully on walls all over the north.

It reminded me very much of the divide in Belfast, Northern Ireland. One mural reads “No surrender”, while another makes it abundantly clear about the politics of this side of the city.

“Kosovo is Serbia and Crimea is Russian,” the words read splayed over the Serbian and Russian flags. Yes, very much like Belfast.

The currency over the bridge is the Serbian Dinar. Which of course I forgot about, so when paying my bill for a coffee and cake, I realised I had none.

No big deal, the lady took my euros, but I’m sure I got ripped off. Ah well.

At least cars have number plates this time. A couple of years back, I distinctly remember the vast majority had no number plates at all.

Illegal of course, and all added to the view that the north was a hotbed of crime. But as I said, it all looks and feels more civil now. Yet it’s a vastly different feel from the south of the city.

The scars of 1999 run deep on both sides, for distinct reasons. As much as I love nothing more than talking politics, one must be incredibly careful about voicing an opinion here.

Bottom line is – don’t. Ask questions for sure, people welcome it, for they want their views to be heard. But don’t give an opinion of our own.

Especially if it contradicts with the one just given. That’s just how it is. I’ve learned that the hard way in such countries over the years.

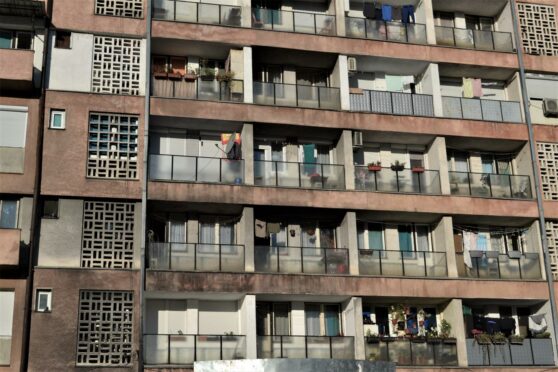

I kept walking and taking photos. Old apartment blocks right out of Soviet Russia stood looking sad.

There are of course new buildings going up, but only for those with money. I’ve read that unemployment is high here. I cannot confirm the figure, but it’s claimed it’s as high as 65%.

As I’ve already mentioned, Mitrovica is one city, in one country, ie Kosovo.

But in reality, it is two countries within one city.

Its two communities are not only divided by a bridge, they also have different languages, currencies, telecommunications and electricity supply.

The north of the city has its own autonomy, and some say is governed by Belgrade, much to the annoyance of Albanians in the south who see that as illegal.

However, according to the Serbians of course, all of Kosovo is Serbia. Never the twain shall meet.

Ethnic Albanian music plays out in the south, while over the bridge, Serbian and Russian pop fills the airwaves and streets.

The Serbs in the north have marked their territory, that’s for sure. And from what I’ve been told, many would prefer the bridge to be physically blocked again, as it used to be. “They don’t want to mix… and like to stick up two fingers to us,” an Albanian told me.

Policing here is extremely complicated indeed. An EU organisation called EULEX is responsible for enforcing laws on both sides of the bridge, but it is highly unpopular, especially in the north.

On and around the bridge itself and on the south side, NATO KFOR troops stand guard.

Last time I was here, when down at the bridge one evening, I asked a female Albanian Kosovo police officer who was open and spoke English: “Who is ultimately in charge here? You? Other officials on the other side, or the NATO guys on the bridge?”

“Good question,” she replied. Yet after much contemplation, was not able to give a definitive answer.

Just weeks before I last arrived, a huge riot took place. Violent clashes from both sides, cars were set alight and tear gas was used.

I asked a NATO soldier what had caused it.

“God only knows. It doesn’t take much. But after riot police got involved, it all died down pretty quickly. It happens like that here, tensions build up, reach boiling point, fizzle out, then it all returns to normal. Whatever normal means here…”

This time I chatted with a Serbian official on the north side, serving in the complicated police force. He was happy to talk, as long as I took no photos and mentioned no names.

“Do you think the bridge will ever fully open to free-flowing traffic and both sides will live side by side?” I asked.

He scoffed before replying: “Who would want that anyway, not me. North Mitrovica is Serbia, not Kosovo. One day all of this town and all of Kosovo will once again be part of Serbia.”

I didn’t argue, just thanked him for his time and moved on.

In any divide, despite what horrors have happened in the past, I believe that when you take flags, politics, rampant nationalism and religion out of the equation, we are all at the end of the day, just people.

And to quote a phrase I used in my book on divided lands: “Minds are like parachutes – they only work when open.”

I have no plans to come back to Mitrovica in the near future. However, If I’m still around, I’d like to come back in, say, 20 years, just to see, out of curiosity.

It was time to leave Mitrovica, and in fact Kosovo itself. Time to move on and journey to Macedonia, or as it’s now officially called, North Macedonia.

A land of huge historical importance, yet due to a recent name change, North Macedonia is one of the newest countries in the world.