There are lessons we must learn every single year as Remembrance Day approaches: no one wants to ban the poppy, it is not offensive to Muslim people, there are no no-go areas for poppy sellers.

But every year, around this time, the same sinister myths and falsehoods surface, peddled by the same people.

The poppy – the symbol of remembrance, the motif of loss, the sign that people who died in conflicts from the Somme to Sangin are never forgotten – has been weaponised to an unhealthy degree.

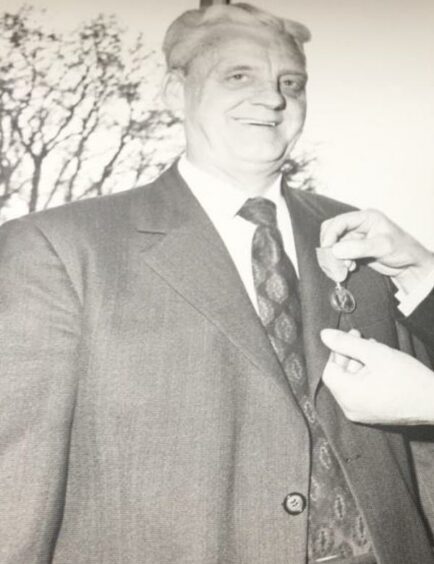

One of my grandfathers was a soldier in the Cameronians, who fought across Europe and beyond in the Second World War. He was seriously injured by shrapnel at the battle of Anzio, as Allies tried to smash through German lines.

My other grandad was a sailor in the Royal Navy. He lost his eye in the battle that ended with the sinking of Hitler’s pride – the Bismarck, one of history’s most feared battleships.

Following in their military footsteps

Me? I was an embedded journalist with the Black Watch in 2009 in Kandahar.

In a bid to immerse myself fully in the conflict in Afghanistan and get a soldier’s eye view, I signed on the dotted line. I joined the Army and served as an infantry soldier in Afghanistan in 2013 and wrote about my experiences.

A friend – who also trained with the Army Reserves before joining a regular battalion for his tour of duty – died there. He was one of the best people: clever, well read, athletic, funny, generous. He had the brightest of futures ahead of him, in or out of the Army.

I wear the poppy for him. I wear it for my grandfathers. And I wear it for the men and women who never got the chance to be mothers or fathers, grandads or grandmothers.

The poppy has been hijacked by those who mean harm

There is no agenda, no hidden meaning, no celebration of militarism, no backing of narrow jingoistic, xenophobic patriotism.

Yet, there are people who want to contort and complicate the symbolism of the poppy. Far right groups, such as Patriotic Alternative and Britain First, regularly aim to hijack Remembrance Day.

They use social media to distort this time when we should be coming together to remember and be thankful.

Take, for example, a recent Patriotic Alternative post eulogising the poppy while simultaneously and ironically spouting the kind of racist rhetoric worthy of the Nuremberg rallies.

It reads: “The result of World War Two sounded the horn for the downfall of the western world and its people.”

According to this vile rant, the process will end with the “eradication of the white race”.

Under this warped worldview, which would not look out of place in Mein Kampf, the poppy is like Kryptonite to Muslim people. This is, of course, utter nonsense.

"Let's take just two minutes

To pause

And remember them"At 11am on 11 November, we will take the time to pause, and pay our respects to our Armed Forces community, past and present. Will you join us? #TwoMinuteSilence pic.twitter.com/poREJKsKAg

— Royal British Legion (@PoppyLegion) November 9, 2021

Muslims were heavily involved in the British war effort in the Second World War.

The British Indian Army totalled 1.4 million troops. Some 430,000 Muslims served, alongside more than 800,000 Hindus and 100,000 Sikhs, with Christians and others.

Soldiers from India and areas that later became Pakistan and Bangladesh made the ultimate sacrifice. So did those from Arab and African countries,

Philosopher George Santayana is credited with the aphorism: “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

We need to keep that in mind as we pause to reflect.

Don’t submit to the poppy fascists

We are now in the period of the annual paroxysm of what veteran news presenter Jon Snow dubbed “poppy fascism”, with people feeling pressured to wear the emblem of remembrance.

One British Army veteran who I follow on social media put it so well. He writes: “Wear a poppy or don’t wear one, it is freedom of choice.

“My late grandad was in the Black Watch and I was in the Guards. Don’t let all those lives lost be in vain. Just be kind and respectful to one another. Rant over.”

And there it is. Let’s learn the lessons of the past.

Do not fall victim to the spreaders of division and hate – the people who want to sow darkness, bitterness and anger.

Keep it simple; remember the fallen, support the living.

Stephen Stewart is an award winning investigative reporter with DC Thomson’s Impact team and a former infantry soldier who served in Afghanistan