Each year, on December 1, we mark World AIDS Day. It is an opportunity to remember more than 30 million lives around the world that have been lost to HIV and AIDS.

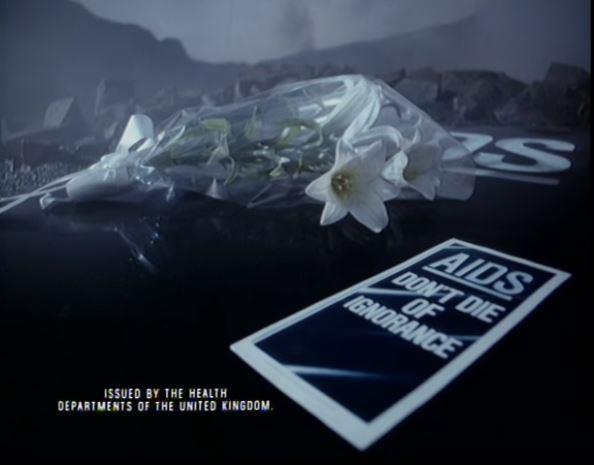

Today’s date has particular significance in the UK. Forty years ago – in December 1981 – the first cases of what we now know as HIV were diagnosed in London. At that time, a diagnosis was a death sentence.

But, today, what it means to live with HIV has changed.

I was diagnosed as HIV positive on June 24 2019.

Just a few weeks earlier, I was working flat out at a London public affairs agency to prepare for an important pitch to a new client. The pressure was high, and it was an intense week of burning the candle at both ends. It was no wonder, I thought, that I was starting to feel a little under the weather.

The day of the pitch was a bright summer’s morning in London. By then, feeling a little ill had developed into a really unpleasant flu. I had lost weight, I wasn’t sleeping, and I was extremely fatigued.

Against my better judgement, I did the pitch. Normally, the post-pitch feeling is a mixture of relief and exhilaration, but I was exhausted. “Well done,” my boss said to me, “but go home, you look awful!”

I felt ashamed of my own relief

That night, I slept for 12 hours straight. When I woke up, I was covered head-to-toe in a rash and could barely move my body. I realised this was not flu.

I decided to get tested and, later that afternoon, it was confirmed that I had tested positive for HIV.

To this day, I still feel a degree of shame at how I felt being told about my diagnosis. I felt an overwhelming relief.

But, in 1981, many men of my age across the UK found themselves in the same position as me. For them, there was no relief to be taken from being told that their hopes and dreams for their lives would never be fulfilled, and that the next time they hugged friends or saw their family would probably be the last.

It doesn’t seem fair that many people – whose partners, friends and family still live today – died and, facing the same diagnosis decades later, I was able to live. Every single day, I feel fortunate and, today, my thoughts are with all of those who lost their lives and their futures in the most cruel of circumstances.

HIV is no longer a health barrier

But HIV has changed and for people diagnosed as HIV positive in the UK nowadays, there is one fact that enables us to feel relief and hope for the future: people living with the virus can live long, happy and healthy lives. That is thanks to truly remarkable medical advances in how it is treated.

Every morning, I take one antiretroviral pill about the size of a five pence coin. That pill doesn’t just keep me alive, it also reduces the amount of HIV in my body to a level that is medically termed as an “undetectable viral load”.

My pill on #WorldAIDSDay

One a day helps keep the virus undetectable, meaning I can’t pass it on.

Today of all days, I’m feeling fortunate & remembering all those who lost their lives to this virus. HIV has changed.

📕 Educate yourself 💉 Get tested regularly. pic.twitter.com/dukvdddUeM

— Paul Robertson (@RobertsonPaulC) December 1, 2021

This helps keep me healthy, but also helps me protect others. Today, people living with HIV who are undetectable cannot pass on the virus to others. We call this “undetectable equals untransmittable”.

In Scotland, 95% of people who are HIV positive and accessing treatment have an undetectable viral load.

For us, HIV is no longer a death sentence. It is a condition we will live with for the rest of our lives – much like diabetes. But it is no barrier to a happy, healthy and long life, and nor should it be a barrier to any chosen career or life path.

Ending lingering stigma matters more than ever

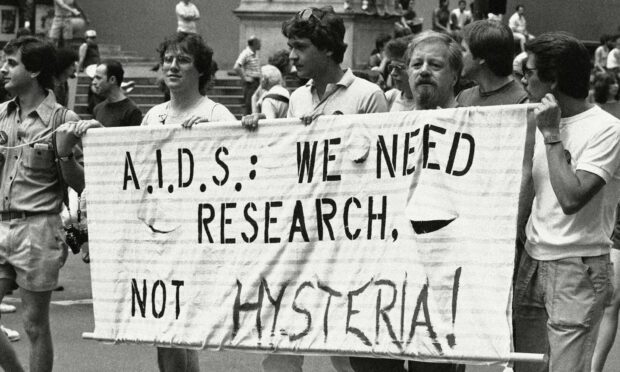

It has taken huge scientific endeavour and medical advances to bring us to this point, but challenges still remain. All too often, people living with HIV still experience stigma linked to discrimination and judgement about their personal lives.

Public attitudes and understanding of HIV have not kept pace with the advances that have been made in medical care. A survey by the Terrence Higgins Trust in 2019 found that almost half of the UK public would feel uncomfortable kissing someone who is living with HIV – despite there being no risk of transmission.

Ending stigma matters, because it is one of the biggest barriers to people accessing HIV testing and care.

We now have all the tools we need to win the battle against HIV – from effective medication to modern testing kits that you can even order to your front door and have a result in minutes.

Everyone in society, whether they are at risk of HIV or not, has a role to play in creating a country where we have zero HIV stigma, zero HIV-related deaths and zero new HIV transmissions.

In 1982, Jonathan Blake – famous for his role in Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners during the miners’ strike – was one of the first people in the UK to be diagnosed with HIV, at Middlesex Hospital. His diagnosis was given the number L1 – London 1.

They soon stopped giving out numbers with HIV diagnoses as the case numbers rose. But I like to think that, if they were still following that protocol, my number might be one of the last. That is possible to achieve – within this decade – and it would be a fitting tribute to the beautiful lives we lost to HIV.

Paul Robertson is head of public affairs at Aberdeen PR firm, The BIG Partnership, and a former SNP adviser